When I caught up with Dorothy Roberts, a professor of law, sociology and civil rights at the University of Pennsylvania, she had just finished a packed book talk at Revolution Books, a small, aptly named bookstore in Harlem. The in-store audience, the event organizer told me, reached fire-code limits. Several people watched from chairs the store’s owners placed on the sidewalk, within earshot of a speaker and in view of a screen in the front window.

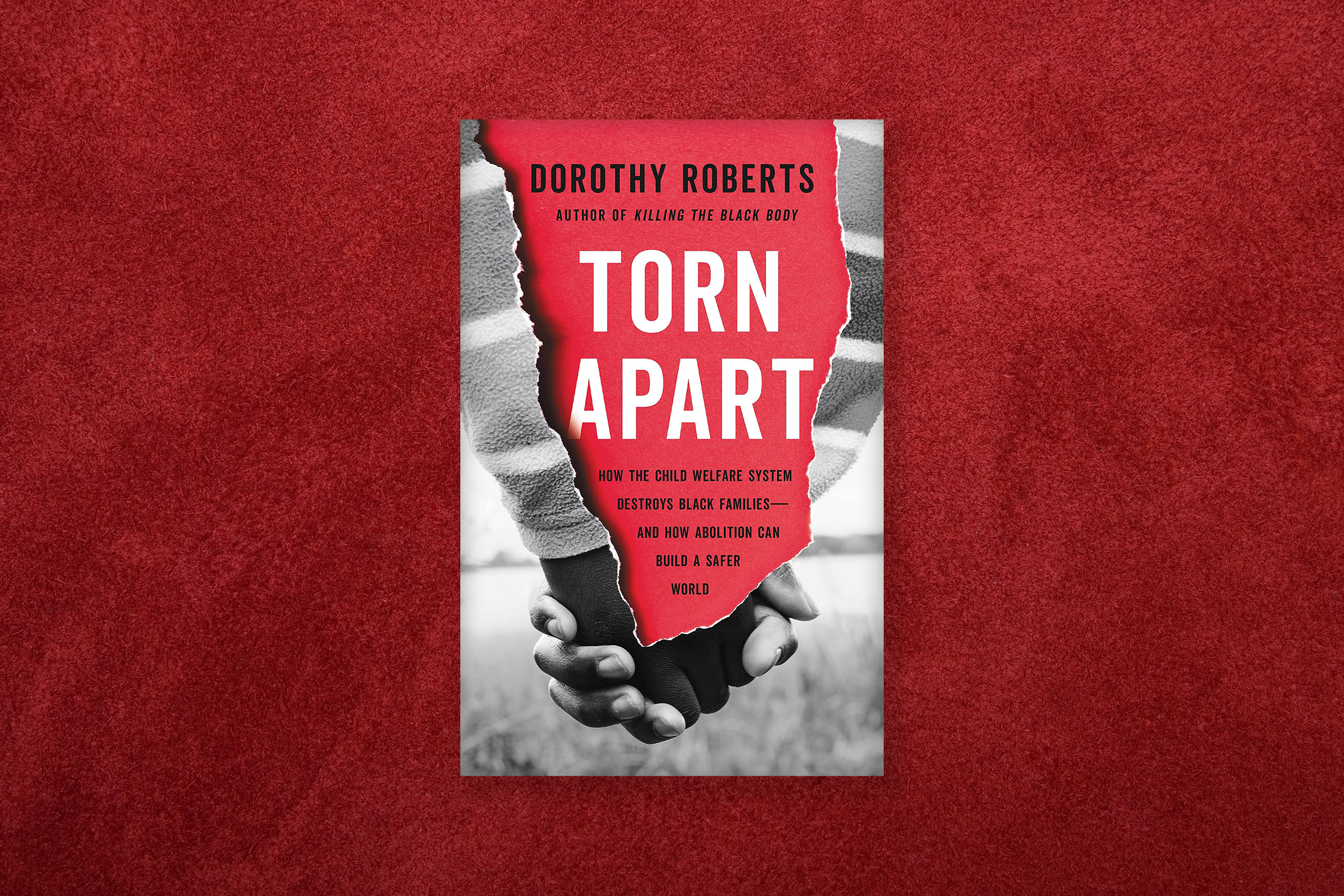

There’s a reason Roberts has such a large following: She has a track record of writing about social problems in ways that both researchers and laypeople recognize to be real. Her new book, Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families and How Abolition Can Build a Safer World, applies that scrutiny to the American child-protective system—a web that Roberts believes doesn’t deserve that name. She argues that child-welfare workers are effectively punishing families, particularly Black families, because they are poor. (Only about 17% of children removed from their homes nationwide are in foster care because of allegations of physical or sexual abuse.) The problem intensified after Clinton-era welfare reform reduced direct aid to poor families, Roberts says; there are now major U.S. cities where 60% of Black children have had some form of contact with child-welfare officials.

In this conversation, which has been edited for clarity and length, as Roberts lays out a disturbing portrait of child welfare in an ostensibly free and wealthy nation, she also finds some evidence that there’s reason for hope.

TIME: What first brought you to the topic of government efforts to enforce child-welfare standards?

ROBERTS: I learned about the child-welfare system intimately when I was working on my book Killing the Black Body, which was published in 1997. At the time, I was doing research on prosecutions of Black women for being pregnant and using drugs. And that’s what led me to look into the child-welfare system. [I] quickly discovered that Black children were grossly over-represented in the system. There was this huge racial disparity, which I then came to see as Black communities being targeted by what I’m now calling “family policing.”

In other words, it’s not just that there are statistical disparities. There are Black communities—especially segregated, impoverished Black neighborhoods—where there is intense concentration of child-welfare-agency involvement, and children are at high risk of being subjected to investigation, to being removed from their homes, to spending a long time in foster care, and for their parents rights to be terminated.

So basically, at every level of action that these agencies can take, there are racial disparities?

Oh absolutely. Disparities in every decision made in the scope of child-welfare proceedings, but also disparities in the bad outcomes for children as well. One of the most striking findings in a recent study is that more than half of all Black children will experience a child-welfare investigation by the time they reach age 18—53%. I mean, that is just an astounding amount of state intervention into the homes of Black children. But then Black children are also more likely than white children to be taken from their families and put in foster care. They’re more likely not to go to college after experiencing foster care, more likely to go to prison. So the outcomes are bad too.

Why are these disparities so pervasive?

I think that the main reason is because the system is designed to deal with the hardships of children who are disadvantaged by structural inequality—including structural racism—by accusing their parents and separating families. I’m saying it that way because some people will say, ‘Well, Black children are more likely to have all these interventions because they have greater needs.’ But, first of all, why do they have greater needs? And secondly, why is the response to their greater need this very violent, traumatic approach of family separation? It’s because of the design of the system to treat poverty in this way. And then also just as importantly, are the stereotypes about Black families that fuel this type of intervention.

Read more: America’s Long Overdue Awakening to Systemic Racism

How do stereotypes prompt child-welfare workers to remove so many Black children from their parents?

There are longstanding stereotypes that Black parents don’t really love their children, that it’s easy to separate the bonds of Black parents and children, that Black children are better off in the care of other caregivers—especially white caregivers. I could go down the list of all of the stereotypes that paint Black mothers as defective, as pathological, as neglectful, incapable of caring for their children. And those stereotypes influence people’s decisions about child abuse and neglect. There’s a whole slew of studies that show that doctors are more likely to suspect child abuse if the child is Black than white, with the exact same injuries. We could trace this back to the slavery era.

Walk us through that history.

Well, we have to go back to the origins of this. Right? [That’s] the enslavement of Black people, when children of Black parents were considered the chattel property of their enslavers. The parents had no right to custody or to raise their children the way they wanted to. And that also meant the families could be separated at the whim of the enslaver for their economic convenience. Part of it also is the sense that children are better off away from their families, and that there isn’t a tight loving bond between Black children and parents. And so there’s less of a sense of the problem that happens from family separation. And I think that stems from the easy removal of Black children from their parents during the slavery era.

And also past that, going into the post-Civil War era and the apprenticeship system, where judges would order Black children to be returned to their former enslavers, on grounds that their parents were neglecting them. Even if you think about the Black “welfare queen,” the idea was she only had children to exploit white taxpayers. There are so many stereotypes and ideas about Black mothers and parents in general. I mean, the stereotype about the Black father is he’s not around at all. So all of those, I think, play into why we have a child-policing system today that investigates a large number of Black families and removes so many—one out of 10 Black children—from their home to be placed in foster care.

Read more: I Searched for Answers About My Enslaved Ancestor. What I Found Was More Questions

When I’ve reported on the child-welfare system in the past, officials would frequently say to me that they had made significant efforts to remove fewer children from their homes or to place children with extended family members. The idea that children of color need to be “rescued” or “civilized” by wealthier white families, they would often tell me, was racist, outdated, and had proved deeply damaging. Do you mean to say that in private, talking with other child-welfare insiders, the emphasis shifts?

Yeah. At [child-welfare researcher] conferences I’ve attended, where there’s the question of whether Black kids should be taken from their homes to address their needs, you don’t hear any discussion about what harm [may come] to the children being taken from their homes. There’s also a study that was conducted in Michigan where they found that at every level—policy makers [and] people who worked in the child-welfare system, including supervisors and caseworkers—there was this assumption that only sometimes gets articulated, that Black children would be better off away from their families or communities. It is true that in some cities, most children are placed with kin. They are not all put into white homes. But that doesn’t mean that those stereotypes don’t still exist.

I was shocked to read in Torn Apart that the most common reason for a child being removed from their parent’s custody is allegations of neglect, not abuse.

Oh, absolutely. The vast majority of children in foster care are there on allegations of parental neglect, which means that the parent has not provided the resources that children need like adequate housing, clothing, medical care, education.

It seems like you’re talking about the need to be more aware of the possibility that the infrastructure to theoretically protect children might be operating more like a policing force that punishes need.

II think you’re right, in a way it’s to punish parents who don’t conform to certain norms. Look at Texas. Gov. Greg Abbott’s directive to caseworkers to investigate the families of children who were provided with gender-affirming care, that’s a very clear case of attacking families who aren’t seen to conform to certain norms. But there’s also a way in which the system has been used historically and today to blame parents for hardships to their children that are caused by poverty and other kinds of structural inequities. By blaming the parents you’re diverting attention away from the structural reasons for these unmet needs.

So what are we to make of the way the Texas directive has galvanized such a strong response, yet many people have not grasped that child-welfare systems have essentially been punishing poverty and Blackness for more than a century?

We could also point out that during the Trump Administration, when family separation at the border was stepped up, there was a huge public outcry with experts pointing out the trauma to children [of] removing them from their parents. Some of them pointing out this is too a form of torture under U.N. conventions. We should point that out. We should object to Governor Abbott’s directive, but the same kinds of incursions on Black families have been happening at a higher rates for decades and it has never gotten that level of public outcry.

Read more: Black Families Are Outraged About Family Separation Within the U.S. It’s Time to Listen to Them

So, what needs to be done here? There are vulnerable children of all races and ethnicities who actually are in danger in their homes.

Fundamentally, we need a completely different approach to child welfare and child protection that doesn’t rely on accusations and investigation and punishing families. You need an approach that is truly caring for children and families, that provides the material resources that children need to be healthy and safe and thriving. We already know that the United States has the largest rate of childhood poverty of any Western nation. It also removes the most children of any Western nation under the name of child protection. [In] a nation that truly provided income support, the kinds of health care, affordable housing, equal high-quality education for all—the vast majority of children in foster care today would not be there.

Really?

There are studies that show that a third of children in foster care right now could be released to their parents if their parents had adequate housing. So, changing the approach would reduce the perceived need to have family separation. Then there still would be, of course, children who are profoundly neglected or physically or sexually abused. But the system we have now doesn’t prevent that from happening. It reacts and sometimes too often reacts too late. It seems like almost every time you hear about a child killed in the home—which is rare—it’s a child known to the system. And that’s part of the story, how the system knew about [the situation]. So something is drastically wrong. This system misses these egregious cases.

It has not been solved by putting people in jail, or by taking children away. We need a fundamentally different way that actually gets to the roots of why there’s so much violence in our society. We have to recognize that the amount of violence in the United States is tied to the gross inequalities in our society.

What do you foresee on the horizon?

Well, one positive development. There are more and more people who have come to the conclusion that this system is so deeply designed to oppress people and harm children that it can not be fixed, [that] we need an abolitionist approach. Policy makers and child-welfare organizations are interested in learning more. And I think that there’s a growing movement to figure out how to dismantle the system. One story that I tell in the book is about a professor at NYU, Anna Arons, [who] wrote an article where she talks about New York City’s accidental abolition during the COVID lockdown. There were all these predictions about children [who were] going to be abused in their homes because child protective services had basically closed down. Well, it turns out that there’s no signs that abuse went up at all.

Even in that period of extreme stress?

Professor Arons argues that the reason why is because there were so many mutual aid networks that sprang into action and we’re distributing ten of thousands of dollars worth of resources to families. The other piece of it was the Cares ACT, the cash assistance that went to families. I think it makes sense that that’s what kept children safe—arguably better than Protective Services.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com