This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

For the first few years of Barack Obama’s presidency, the White House persuaded immigration activists to hold their fire. The incoming Obama team had to first rebuild the economy and make sure Detroit’s automakers didn’t shutter after the 2008 financial meltdown. Then came a massive healthcare reboot. Then Supreme Court nominations, a Republican takeover of Congress, and the President’s own re-election.

And then. And then. And then. There always seemed to be something keeping immigration from the frontburner. By 2014, long-simmering frustrations among immigration-rights advocates were ready to boil over and at the annual opening gala of the National Council on La Raza, as the umbrella group of advocacy and social services group now known as UnidosUS was called at the time, Obama himself was targeted for blame. “Deporter in chief” burned, especially coming from the head of one of the largest Latino organizations in the country whose alumni had embedded throughout the Obama Administration.

It clearly hurt the President, who had won re-election in 2012 with the backing of 71% of the Hispanic vote despite activists’ already deep frustrations with his first-term inaction. Two days after the gala, Obama took up his own defense: “I think the community understands I got their back and I’m fighting for them.” And a few months later, Obama rolled out expanded executive actions that—had the Supreme Court not curbed his powers—would have expanded protections to almost 5 million undocumented immigrants. During his last year in office, deportations fell to the lowest levels since 2007.

But the bell had been rung. Distrust was an open characteristic of the White House’s relationships with immigration groups from that point on. Protests flared as Obama still oversaw close to 3 million deportations over eight years. And while his efforts to patch the immigration system helped in the short term, they didn’t all last. And Donald Trump had made anti-illegal immigration a plank of his identity quickly went about dismantling protections.

So why does this history matter in Washington right now? To channel former President George W. Bush’s mangled deployment of a cliché: “Fool me once, shame on—shame on you. Fool me—you can’t get fooled again!'” As gun-violence-prevention groups work to build support for moves to reduce deaths, they’re also studying what happens when allies give an Administration a pass, especially when a political majority has every chance to flip Congress into Republicans’ hands after November’s elections. And they don’t like the historical precedent of deferring to the White House, especially one whose power may have an expiration date.

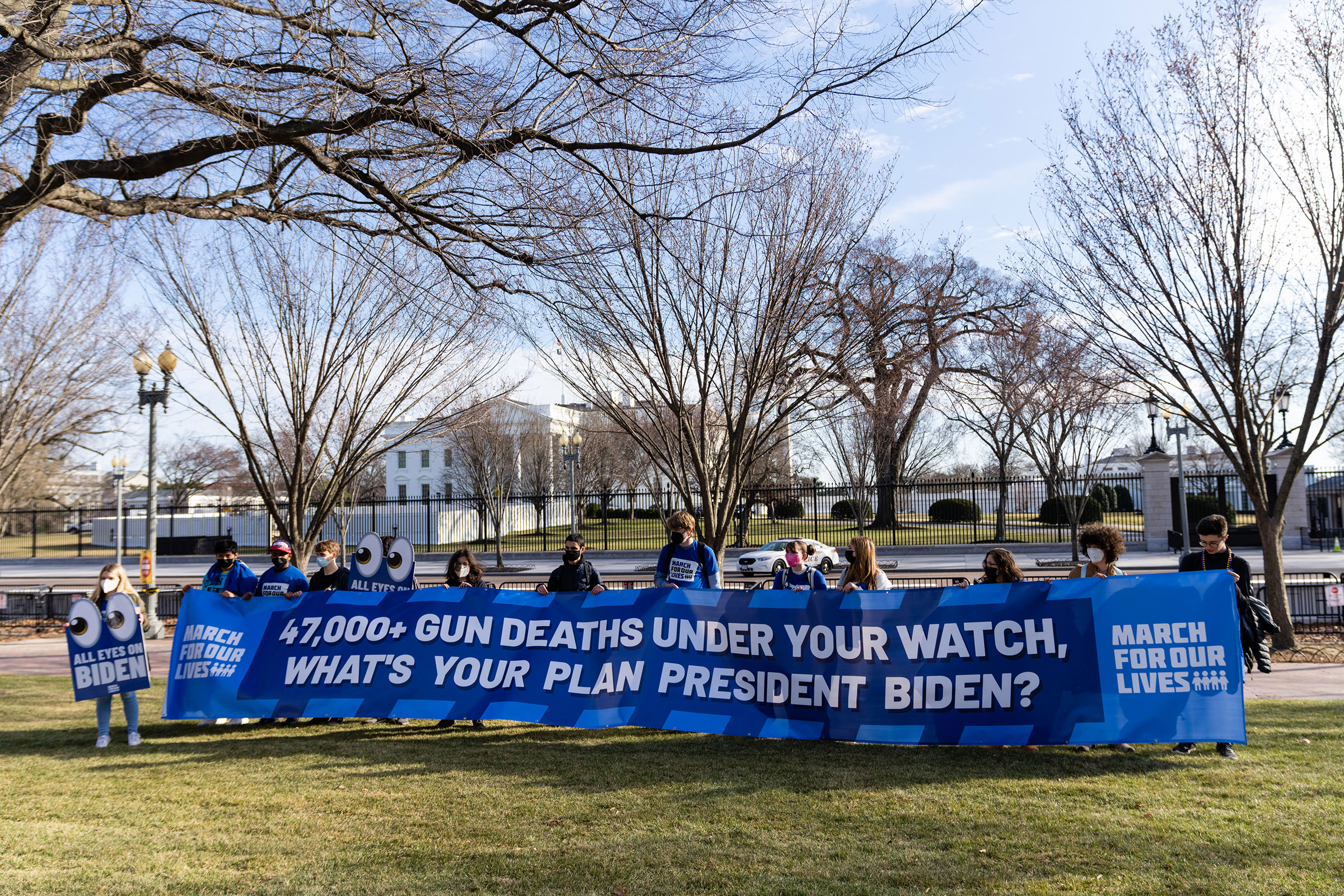

“He’s a friend to the movement, sure. We can call him that. But he’s not a leader, and that’s what we really need,” says Zeenat Yahya of March For Our Lives, the youth movement that emerged in the wake of the 2017 high school shooting in Parkland, Fla.

March For Our Lives and Guns Down America on Friday published Biden’s report card on gun violence, and the grade is a D+. The timing is matched to the one-year anniversary of Biden standing in the Rose Garden with an agenda to curb mass shootings with little to show. “The reality is: a year later that commitment has proven to be false,” says Igor Volsky, the co-founder and executive director of Guns Down America.

In conversations with leaders of the groups, it’s clear this isn’t the verdict they wanted to deliver. Neither group is explicitly political, but there is a non-zero chance that almost everyone involved in official and unofficial roles with them voted for Biden, who ran an aggressive campaign messaging against gun violence. For good reason, they thought Biden—who managed mass shooting response and outreach for Obama as the consoler-in-chief—was their guy.

But as the history of immigration reform shows, an affinity for a politician is no substitute for action. No one flinched when MoveOn protested the Bush Administration. But the political world noticed when the then-obscure network of super-rich libertarians and conservatives turned the keys on a political machine that would come to be short-handed as The Koch Brothers. The Obama White House noticed when its allies in immigrant-rights circles started showing up at the gates with protests. For all of the powers of the presidency, the ability to form effective coalitions is one of the underrated ones, and at the moment one that is proving a challenge for Biden.

To be sure, Biden alone can’t fix the scourge of gun violence in this country, where privately owned guns outnumber people. But just last weekend the latest mass shooting left six dead in Sacramento, and the White House dutifully put out a statement offering thoughts and prayers. There’s always the call for action, but then it falls by the wayside. Without any real accountability, politicians skate by on the bare minimum of performative signals. And the stakes are too high in the estimation of these activists.

There was a time not that long ago when a signal from the White House to shutdown criticism was sufficient. President Bill Clinton presided over both Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and the Defense of Marriage Act—now widely seen as major setbacks for LGBTQ rights—yet was still welcomed in 1997 as the first sitting commander-in-chief to speak to the Human Rights Campaign’s annual gala. The White House was still seen as the political power center of Washington and actors in this space had deference to those established poles. Proximity means power, and only friends get invited to the table.

But things change. The Forever Wars, the economic crisis of 2008 and the last few years’ reckoning on gender, race and policing have left Americans rightly sour on trusting those with power. In fact, Gallup has been quantifying the shift since 1993 and the results should frighten anyone looking for public confidence as a source of authority. Public confidence in the presidency itself hit a high of 58% in June of 2002, as the Bush Administration was leading a seemingly successful disposal of the Taliban in Afghanistan but still hadn’t expanded the Global War on Terror into Iraq. That number plummeted to 26% in June of 2008 and remained parked at 38% as of June last year. In other words, it’s easy to ignore the call coming from a number that begins (202) 456-xxxx when so few people are heeding the words being dispatched from the West Wing.

As gun-violence-prevention groups look to keep Biden moving in the right direction, their public break with the White House certainly comes with risks. While no one would directly criticize the players nominally running the policy review, they know their open critique will win them few friends. But like any maturing movement, gun-violence-prevention activists are starting to have their confident years. They aren’t asking for permission the way they used to, and deference is less attractive than before. They have mailing lists and text-messaging databases that can rival most national political groups, and they’re built from grassroots followers who will do far more than write checks or retweet a meme.

And if the Biden White House doesn’t get that, they should. After all, it wasn’t that long ago that some current Administration officials were holding signs just outside the White House gates to protest Obama’s immigration policies.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com