The world’s attention is rightly focused on the unfolding horror in Ukraine. Images of destruction and death wrought across that nation, and the harrowing experiences of refugees fleeing in their millions, testify to the tragic reality of war. And in the capitals of Europe, something once thought an impossibility—a large-scale 21st century war on the continent—has now become all too real, awakening once idealistic nations to the hard truth that such senselessness violence has not been eliminated from our modern, globalized world.

The scenes in Kyiv and Mariupol should serve as an abrupt wakeup call to those public figures who have talked loosely about inviting open warfare in our world. Most of them have never seen war themselves, or borne witness to its human cost.

In this grim moment it is important to think through, and coldly reassess the dangers presented by other potential conflicts that could be sparked by today’s geopolitical tensions. The most significant among these is, without doubt, the possibility of a war between the U.S. and China. It is a prospect that we must now acknowledge is no longer unthinkable.

Were such a conflict to begin, whether over a crisis in the Taiwan Strait, in the South China Sea, or any number of other unpredictable flashpoints, such a war would almost certainly be many times more destructive than what we are seeing in Ukraine today. It would be a conflict with vast scope for escalation across every domain, from the seas to space, and likely to draw in many other countries across the world, including America’s allies in the Pacific. Such a conflict would be a catastrophe for both countries—and for us all.

War between the United States and China is not inevitable. But U.S.-China relations continue to spiral downward, their strategic relationship adrift and buffeted by growing global crises. Muddling through will be wholly insufficient to avoid conflict. To avoid sleepwalking into a war, both countries must construct a joint strategic framework to maintain the peace—and quickly.

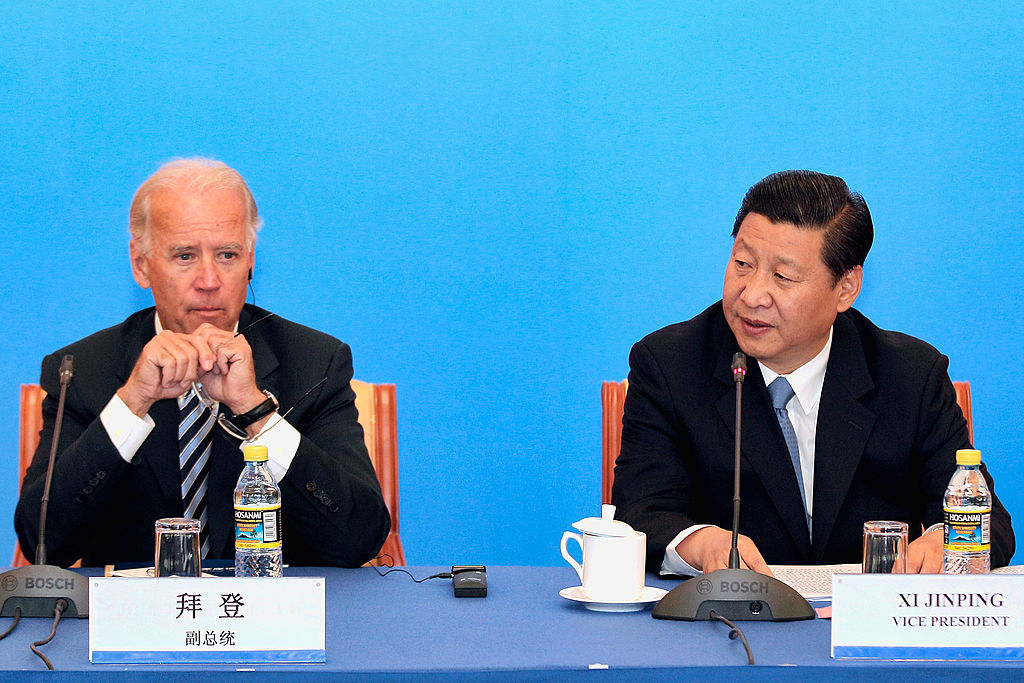

In my new book, The Avoidable War: the Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict between the US and Xi Jinping’s China, I offer one such framework, which I call “managed strategic competition.” The idea is relatively simple.

First, the United States and China must have a clear, granular understanding of each other’s irreducible strategic redlines in order to help prevent conflict through miscalculation. Each side must be persuaded to conclude that enhancing strategic predictability advantages both countries, strategic deception is futile, and strategic surprise is just plain dangerous. This will require a focused, detailed diplomatic understanding on Taiwan.

Second, both countries must then embrace the reality of their competition—that is, to channel their strategic rivalry into a competitive race to enhance their military, economic, and technological capabilities. Properly constrained, such competition can deter armed conflict rather than tempt either side to risk everything by prosecuting a dangerous and bloody war with unpredictable results. Such strategic competition would also enable both sides to maximize their political, economic, and ideological appeal to the rest of the world. The strategic rationale would be that the most competitive national system would ultimately prevail by becoming (or remaining) the world’s foremost superpower and eventually shaping the world in its image. May the best system win. And I’m confident which one I’d bet on.

Third, this framework would create the political space necessary for the two countries to continue to engage in strategic cooperation in the areas where their national interests align. These spheres include: climate change, preventing the next pandemic, and maintaining global financial stability.

Finally, for this compartmentalization of the relationship to have any prospect for success, it would need to be carefully and continuously managed by a dedicated matching of cabinet-level senior officials on both sides. For the U.S., this also means any such framework would need bipartisan buy-in so it could withstand the turbulence of domestic politics. For a priority this important, this should by no means be impossible.

This approach will face criticism in both Washington and Beijing for not being sufficiently sensitive to each side’s national interests. To some in Washington, it will smack of appeasement. This is false: cold, realistic deterrence is at the core of any comprehensive strategy toward China. Meanwhile many in Beijing will argue it doesn’t sufficiently account for China’s core interests on Taiwan, and broader national pride. But as Moscow just learned in Ukraine, war and economic devastation would suit China’s interests far less.

Ultimately, my challenge to critics of managed strategic competition, and putting guardrails to the U.S.-China relationship, is simple: Come up with something better. There is little time to waste.

I have long studied, lived in, and come to deeply respect both the United States and China. The prospect of war between the two nations would be catastrophic. And, watching the destruction in Ukraine, I cannot help but recall the memory of marching as a small child in our annual ANZAC Day parade—the Australian equivalent of Memorial Day—in our tiny country town with my father, who had fought in World War II, alongside elders who had fought in World War I.

The world managed to sleepwalk into the slaughter of that first Great War, which claimed more than 15 million lives. With our eyes now wide open, we will have no excuse if we fail to avoid walking into yet another global catastrophe today.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com