There are people in their 30s who have never lived in a world without the Hubble Space Telescope peering into the cosmos. The venerable observatory was launched in April 1990, back when George H.W. Bush was in the White House, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was the number one box office hit, and gas went for a buck a gallon. It’s only fitting then that this week, the very old telescope made a very important discovery of an exceedingly old star—the oldest, indeed, that’s ever been detected.

As NASA announced, a new paper published in Nature reports that Hubble has spotted a star that is a staggering 12.9 billion years old, meaning it existed when the universe was only 7% of its current age. The previous record holder, spotted by Hubble in 2018, was a comparatively young 9 billion years old, shining when the universe was 30% of its current age.

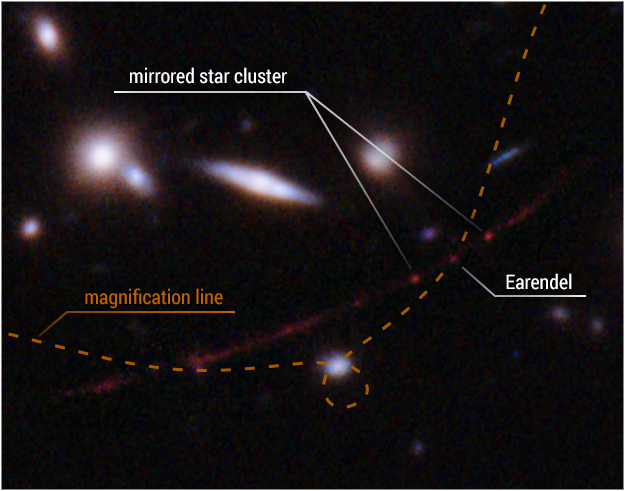

The new star, dubbed Earendel, which means “morning star” in Old English, does not even exist anymore—its light has been traveling to us over the past nearly 13 billion years, long after the star itself has winked out. The late Earendel might not have been detected at all if it weren’t for a trick of physics and optics known as gravitational lensing. Originally posited by Albert Einstein, gravitational lensing occurs when light from a distant object passes around a closer massive object (like a star). The gravity of the intervening object acts like a sort of lens, distorting and magnifying the image of the more distant one.

In this case, the lens was not just another star or even a galaxy, but an entire galactic cluster. Earendel’s position in space is especially fortuitous, with its light passing directly over a discrete ripple in spacetime—known as a “caustic”—caused by the cluster. The caustic, in a sense, magnified the magnification, making the star appear to shine all the brighter.

“Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges, with the light from millions of stars blending together,” Brian Welch, an astronomer with Johns Hopkins University and the lead author of the paper, told NASA. “The galaxy hosting this star has been magnified and distorted by gravitational lensing into a long crescent.”

Welch and his colleagues have determined that Earendel was about 50 times the mass of our sun and millions of times as bright. It also would have been made up exclusively of hydrogen and helium, lacking any of the heavy metals that exist in the more modern universe. As such, Earendel is what NASA calls “the first evidence of the legendary Population III stars,” which are the first stars to have lit their nuclear furnaces after the Big Bang.

Earendel may have been Hubble’s to find, but the aging telescope will now pass the work of studying the object in greater detail onto the brand new James Webb Space Telescope, which was purpose-built to observe in the infrared spectrum in which the ancient star principally shines. Indeed, Webb will do even more than that.

“With Webb we will see stars even farther than Earendel,” Welch told NASA. “I would love to see Webb break Earendel’s distance record.”

This story originally appeared in TIME Space, our weekly newsletter covering all things space. You can sign up here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com