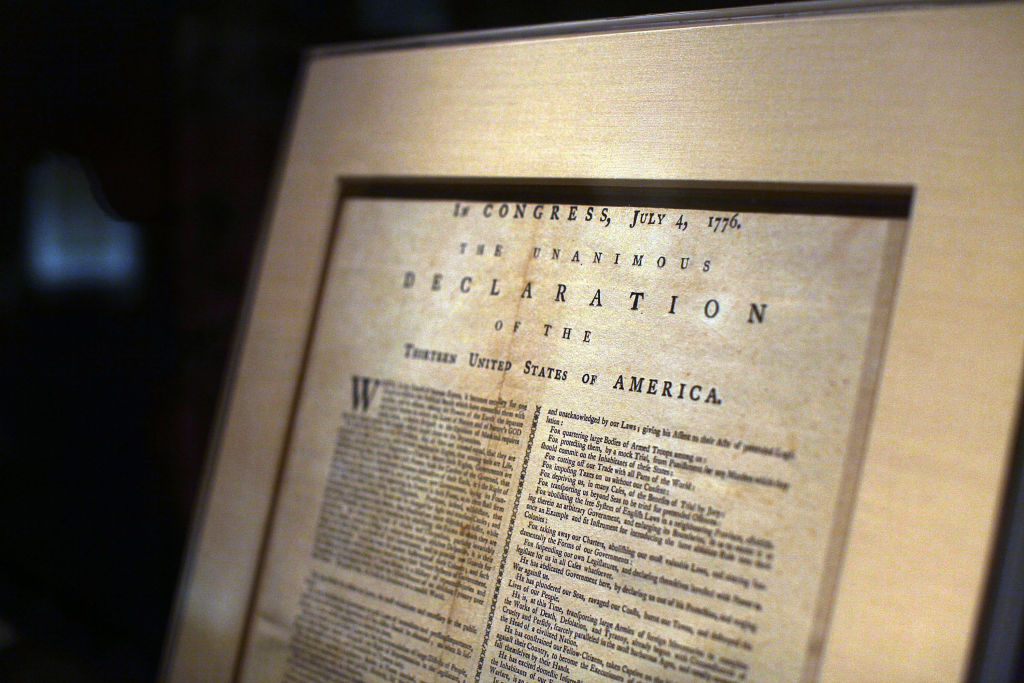

The big event is still more than four years away, but from federal agencies to local museums, the nation’s history community has already begun planning for the 250th anniversary of the United States. Beyond simply celebrating the Revolution, the “Semiquincentennial” commemoration is also an opportunity to share American history in ways that fully explore the diverse people and complex events of our country’s past.

As debate over what history is and who controls the nation’s historical narrative continues to be a partisan lightning rod, it is a minor miracle the 250th has so far taken shape beneath the radar. Although the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission and its private, nonprofit partner the America250 Foundation have been accused in recent weeks of a variety of misdeeds (including discrimination, which the foundation denies), the actual content focus of the 250th—its approach to history—has remained out of the limelight. That peace seems unlikely to last long.

Over the next few years, as planning for 2026 collides with the Presidential election of 2024, the attention of both politicians and the public will turn more directly to the Semiquincentennial. The controversies sure to ensue stand to have a profound effect on the way many Americans understand our shared national past for decades to come.

After all, major anniversaries have a remarkable ability to shape public engagement with history. Nearly 50 years ago, as historian M.J. Rymsza-Pawlowska has shown, the 1976 Bicentennial transformed how Americans connect with history and understand our national story. When President Richard M. Nixon tried to steer federal Bicentennial planning toward an unquestioning celebration of American achievement, communities across the country responded with a vision of American history that included a wider range of voices, correcting gaps and silences in the mainstream historical narrative. Grassroots efforts led to the creation of thousands of new museums, historical societies, and history programs that shared a more complete story of the American past. These institutions and programs form an important part of today’s history infrastructure, and a more expansive conception of history has become core to professional historical practice.

Today, the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission has embraced this particular Bicentennial legacy, intentionally planning a commemoration of U.S. history driven by local interests. Established by Congress in 2016, the Commission includes members of Congress, heads of major federal agencies related to history and education, and 16 private citizens appointed by both parties. Together with America250, the Commission has set the ambitious goal of making the Semiquincentennial “the most inclusive commemoration in our nation’s history.”

The effort to explore history through multiple perspectives extends to state-level planning as well. In the past few years, 21 states established commissions tasked with planning the 250th anniversary commemoration, and 11 more have introduced legislation to create state commissions already in 2022. In South Carolina, the state’s 250th commission plans to share history “from all points of view,” including “the beauty and the warts and the terror of it all.” Expanding on traditional commemoration approaches, the Nebraska 250th commission will “promote under-represented groups from the American Revolutionary War, including, but not limited to, women, American Indians, and persons of color.” Many other states have similarly prioritized an approach to the 250th that includes diverse perspectives, leaning on their state’s history and museum community to develop the commemoration program for 2026.

Though these national and state-level efforts have thus far avoided the kind of overt politicization tied to other forms of public engagement with history, there have been several near misses.

When Donald Trump established the “1776 Commission” in the final months of his presidency—part of his effort to narrowly define the terms of “patriotic” history—he left out mention of the federal Semiquincentennial Commission, which, during his tenure as President, had advanced plans for a broad commemoration of the American Revolution. Similarly, in the summer of 2020, Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas introduced a bill to ban the 1619 Project from being taught in schools, as part of a backlash that sees the project (which tells the story of American history through the lens of slavery) as insufficiently reverent toward the Founding Fathers and the legacy of the Revolution. Cotton made no mention, however, of the upcoming 250th anniversary—despite being an appointed member of the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission.

At the state level, the disconnect between 250th planning and the wider history wars is even more stark. Many of the same legislatures that passed bills to create 250th commissions dedicated to exploring the full depth of the American past have also introduced hundreds of so-called “divisive concepts” bills to restrict the teaching of slavery, racism, and violence in U.S. history. Such bills frame nearly all shameful parts of our history as merely momentary deviations from the march of liberty and progress.

With the anniversary more than four years out, the 250th is still just a bit too distant to register much concern among either the public or elected officials. Audience research conducted by state history organizations has suggested that few people are yet thinking forward to 2026. So, although Semiquincentennial plans are developing alongside broader arguments over what history is or should be in recent years—providing plenty of tinder for turning the 250th into a political fire—the immediacy and passion of education issues seem to have offered lower hanging fruit, leaving 250th planning largely unscathed.

The history wars and the Semiquincentennial have thus proceeded in parallel, though they seem certain to intersect in the coming years. Yet for history professionals, advancing Semiquincentennial plans against the backdrop of current controversies has been strategically useful, offering new perspective on the effort required to bring to fruition a commemoration that shares a more honest story of our nation’s past.

In Utah, planning for an inclusive 250th commemoration is proceeding amid the growing national debate about what history is and whose stories count. To fortify efforts to share the full history of the state, Utah’s Division of State History is deliberately working in concert with a broad range of stakeholders and community partners. That includes collaborative efforts such as “Peoples of Utah Revisited,” a project supported by the state’s leadership that demonstrates a strong commitment to amplifying diverse voices.

“We know and fully understand the arc of the national dialogue,” Division Director Jennifer Ortiz told me recently. “If we do this work together, we’re going to be stronger.”

Other organizations around the country are taking a similar tack, using collective effort to slowly shift public knowledge of the past toward a broader understanding of who and what makes up U.S. history. Though some in the field want to see a wholly unapologetic approach, these more deliberate strategies can help maintain public trust, and—amid heated partisan controversy—provide the strong foundation required to sustain programs that encourage critical engagement with history.

Today, it is a vocal minority that actively opposes more complete, more nuanced historical narratives. Recent research reveals that most Americans see the value of including multiple perspectives in history, think it’s acceptable for people to feel uncomfortable when learning difficult subjects, and believe an increased focus on the history of race and slavery is good for society. Museum audience researcher Susie Wilkening has calculated that fewer than 20% of Americans have truly “anti-inclusive” attitudes.

Planning for 2026 is bound to be fraught. As 250th programming comes into sharper focus over the next few years, both legitimate debate and bad-faith point-scoring will drive a major public conversation about how we commemorate the nation’s complex past. Yet as plans for the Semiquincentennial progress, today’s partisan debates about history enable government agencies, museums, scholars, and the public at large to more effectively chart a path forward for history work that is both inclusive and sustainable.

Dealing with the current history controversy shows that, as 2026 nears, museums should proceed deliberately, coordinating with stakeholders to help audiences recognize that history, like detective work, requires us to evaluate all available perspectives and update our understanding as new evidence comes to light. Americans among the majority that values deep, thoughtful history can voice their desire for a commemoration grounded in that approach—particularly in states that have not yet created 250th anniversary commissions.

With four years left to prepare, all Americans who support continuing to explore the nuance of the past can play a role in overcoming politically motivated attempts to sanitize this anniversary. By working together, we can ensure the Semiquincentennial can help us make progress toward a more just society by providing a widely shared and complete understanding of our nation’s history—one that endures as a lasting legacy of this anniversary.

John Garrison Marks is the Senior Manager, Strategic Initiatives and the Director of the Public History Research Lab at the American Association for State and Local History. He is the author of Black Freedom in the Age of Slavery: Race, Status, and Identity in the Urban Americas. He is on Twitter at @johngmarks.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com