During his campaign for the Oval Office, President Joe Biden made criminal-justice reform a focal point, calling out many problems with the system: over-incarceration, a lack of focus on redemption and rehabilitation, racial and socioeconomic disparities, “urban gun violence,” and more.

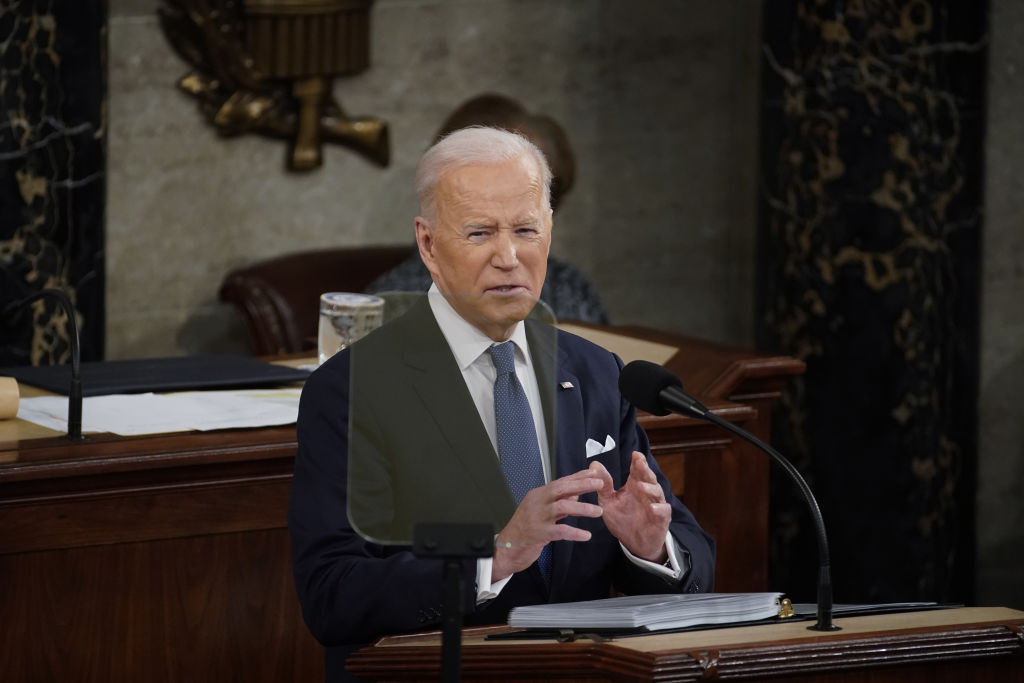

When it comes to having turned those promises into reality, a little more than a year into his first term, criminal-justice experts give him a mixed report card. During his State of Union address on March 1—which happened to be the first day of National Criminal Justice Month—Biden didn’t have much to say about criminal justice reform. When he did speak about criminal justice issues, he primarily focused on calls to “defund the police,” which Biden pushed back against, arguing that the police in fact need more funding. (This is a position about which he’s been very consistent.)

“We should all agree: The answer is not to defund the police. The answer is to fund the police with the resources and training they need to protect our communities,” Biden said during his address to the country, garnering applause from both sides of the aisle.

Making progress

The President has followed through on some of his criminal-justice campaign promises, or at least tried. Through the Build Back Better Plan, he proposed $5 billion to go toward community violence intervention programs, with the hopes that this would fund training, research, grants, and data collection for gun-violence prevention on the ground. This is all in addition to billions in funding for law enforcement. The Build Back Better plan, however, is currently stalled in the Senate.

In terms of tackling gun violence, he’s made noteworthy investments for community-led initiatives. As part of the American Rescue Plan, $350 billion for state and local funding is permitted to go toward community violence intervention programs.

He’s also nominated 75 people to federal courts, with 40 of them confirmed. Having said he would improve diversity among the ranks of people who enforce the justice system, over 60% of his nominees were people of color and 75% of them were women, according to a report by the Alliance for Justice. Under his presidency, 37 U.S. Attorneys have been nominated, 20 of whom are Black along with 13 women. Before Biden’s presidency, women of color only made up 4% of sitting federal judges. He’s nominated 31 women of color for federal judge positions in his first year, compared to two for former President Trump and nine for former President Obama.

While on the campaign trail, Biden said he would eliminate the federal death penalty. Though it has not been eliminated, there is currently a moratorium on it. (The Supreme Court recently reinstated the death penalty for Boston Marathon Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.)

Another one of his promises included ending the federal government’s reliance on private prisons. Biden did order the Department of Justice (DOJ) not to renew contracts with private facilities in 2021; however, those same kinds of facilities are still used for federal detention centers, including ones overseen by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), since ICE is not part of the DOJ.

“I think given the difficult political atmosphere that Biden has navigated, he’s had some modest success addressing criminal justice issues,” Thomas Abt, a senior fellow with the Council on Criminal Justice, tells TIME. “I think you have to look carefully at what he can do through executive action and what he can’t do. You can only really hold him responsible for the things that he could do through executive action.”

Stalled out

Others, however, think Biden bears a particular duty to fix the justice system, and that he has a ways to go.

“Biden has a unique responsibility regarding criminal-justice reform, given his large role in creating and crafting a lot of the policies that got us in this mess in the first place,” says Ojmarrh Mitchell, a criminal-justice professor at Arizona State University.

Mitchell is alluding to the many policies and positions Biden took on criminal-justice policy as a Senator in the ’80s and ’90s—most notably his role in the 1994 Crime Bill, which many argue led to the mass incarceration of Black and Brown people across the country.

“Joe Biden is not a regular president when it comes to justice issues. He is a President who has a long history of being in favor of the most draconian and racially biased policies we’ve seen in decades,” Mitchell says. “He has a greater responsibility to right the wrong.”

The President said that he would revamp clemency power and use it for non-violent offenders and those incarcerated on drug crimes; Biden has not commuted or pardoned anyone so far. The U.S. Sentencing Commission, which helps govern and address disparities in federal cases, currently has six open seats; Biden has not nominated anyone for the commission. Reducing the prison population was supposed to be another priority in Biden’s administration; there has not been much follow-through on that: The prison population is at around 1.8 million and while there was a period of decarceration at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, that has since stalled.

And David Chipman—Biden’s pick to lead the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF)—did not make it through tense confirmation hearings, leaving the agency leaderless and underfunded. Despite his progress on gun violence, some experts and advocates would like to see Biden appoint a gun-violence political leader or “czar” to oversee the Administration’s efforts to address the problem.

“If you’re going to make this major investment and the money eventually comes through, you need to have White House leadership to make sure that it’s done right,” Abt says. “A czar position can really harmonize the administration’s various efforts on gun violence.”

Read more: Why the Federal Firearms Agency Can’t Find a Permanent Director

Perhaps the most notable failure of criminal-justice reform in the past year, however, has been the George Floyd Policing Act‘s not passing through the Senate. Though this was not Biden’s fault, he did promise to put together a police oversight committee or “task force”—which could have the power to address excessive policing and hold law enforcement more accountable —but that hasn’t come to fruition either. Biden could create an oversight committee without going through Congress.

And then there’s the matter of “defund.”

“I think he’s it’s been very politically savvy on [the police] issue,” Arizona’s Mitchell says. “He’s talking about police reform but he’s not talking about it in the more radical ways that Black Lives Matter and the Defund the Police movement have been talking about it.”

So, looking to Biden’s second year in office and beyond, experts like Mitchell are focusing on not only the successes the President has accomplished but also on his ability to do more.

“He’s made some progress that shouldn’t be minimized,” Mitchell says, “but there’s so much more he could accomplish if he made criminal-justice reform an urgent part of his administration.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com