The misogynistic logic of patriarchy is curiously circular: women cannot govern because they never have. But this big lie rests upon a bed of induced historical amnesia, the work of numberless erasures and omissions, collectively sending the message that the women who have ruled haven’t earned the right to be remembered.

This logic doomed the legacies of the sixth century Queens Brunhild and Fredegund. They ruled over most of Western Europe for decades, leading armies, revamping tax policy, undertaking public works projects, and negotiating with kings, emperors, and popes. They fought a decades-long civil war— against each other. And yet today, few know their names.

There is no question of the queens’ transformation in historical chronicles from fierce powerbrokers to mere footnotes being accidental, the result of poor translations, sloppy transcriptions, or even a handful of scribes with personal axes to grind. It was a coordinated and methodical effort. And it was, in part, made possible by the biblical story of Jezebel.

Jezebel was the Phoenician queen who became the archetype of the wicked woman— promiscuous, greedy, and godless. The crimes leveled against her include forcing pagan idolatry upon the Israelites and harassing the prophet Elijah.

But this biblical story was written centuries after Jezebel’s death, and its version of events don’t match up with what scholars now know to be true. For example, Jezebel did not import a pagan god; that deity was already well-established. In fact, the kingdom already enjoyed ethnic diversity and religious pluralism. But when the fundamentalist prophet Elijah mocked and then slaughtered hundreds who did not believe as he did, Jezebel threatened to punish him. Frightened, Elijah fled and then plotted revenge. When, many years later, Elijah and his followers triumphed, Jezebel did not beg for mercy. Instead, she met her end defiantly, dressing in her finery and applying kohl to her eyes while awaiting her murderers.

After her death, Jezebel was branded a harlot. Her real crime, though, seems to have been something else entirely. In one translation of the Bible, she dares to tell the male prophet that she is his equal: “If you are Elijah, so I am Jezebel.”

Queens Fredegund and Brunhild similarly presumed themselves equal to men, but Jezebel’s story provided a convenient blueprint for rewriting their legacies after their deaths.

Queen Fredegund, a former palace slave, died peacefully in her bed. Her body was embalmed and wrapped in linen strips that had been soaked in oil and a mix of nettles, myrrh, thyme, and aloe. Then her body was dressed in her finest silks, draped with her most impressive jewels, and shelved away in a plain stone sarcophagus. The queen was laid to rest in Paris with great fanfare, as she had desired, and next to her husband in the church now called Saint-Germain-des-Pres.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In contrast, Brunhild, once a sophisticated and well-educated princess from Visigothic Spain, met her end in a muddy field. Brunhild was gruesomely executed by Fredegund’s son, King Clothar II. Afterwards, he went to great lengths to make sure Brunhild would never enjoy a prestigious resting place: “Her final grave was the fire. Her bones were burnt.”

Immediately after Brunhild’s execution, King Clothar II quickly moved to obliterate the memory and legacy of his aunt and, curiously, his own mother. At the beginning of his reign in his most public act, the 614 Edict of Paris, he erased Brunhild and her descendants entirely. The document lists tolls and taxes going back several decades, but he makes no mention of Brunhild, her son, or her grandsons. The entire line was wiped from the public record.

More surprisingly, Clothar II makes no mention of his mother, either, even though Fredegund had issued her share of tolls and taxes. Clothar II was presumably a dutiful son who said the usual Masses for the repose of his mother’s soul, but he did not allow her any legal recognition. Nor did he commission any poems or erect any churches in Fredegund’s honor. He did not seek to have her made a saint—even though the bar was quite low at the time. The chronicles, though, were scrubbed of reports of Fredegund’s potential infidelities.

While Fredegund’s image was sanitized, Brunhild was cast as a “second Jezebel.” Years earlier, Brunhild had tangled with a monk named Columbanus. He came from an Irish monastery known for its strict austerity and copious use of corporal punishment; his goal was to found more monasteries based on this model in continental Europe. He also planned to forcefully convert any remaining pagans in the border regions, although he was not terribly persuasive as a missionary. In areas where the common folk still revered Woden and his oak trees, rather than trying to win them over with sermons, Columbanus simply cut down their sacred trees and set fire to their temples.

When monks financed by Brunhild first landed in Britain to convert the Anglo-Saxons, they behaved similarly. But relatively quickly, the pope decided upon a more moderate approach. Pagan temples could be rededicated to the Christian God and pagan traditional feasts and sacrifices associated with various saints and martyrs. But Columbanus did not bow to the authority of the Roman Pope, and he certainly didn’t compromise. He stuck with his scorched-earth methods, and he was forced to move on more than once when his monks were murdered in retribution.

Read more: 9 Women From American History You Should Know, According to Historians

Like Jezebel and Elijah, Brunhild and Columbanus were destined for some sort of conflict. Columbanus was an uncompromising fundamentalist; the queen had a more cosmopolitan worldview, as evidenced by the sort of missionary work she financed and her tolerance of the Jews in her kingdom. While traveling through Francia, Columbanus made it a point to condemn one of Brunhild’s grandsons for his lax sexual morals. He also publicly humiliated Brunhild by refusing to bless her young great-grandchildren because they were illegitimate. Eventually, after clashes with local clergy and his fiery calls for Brunhild’s downfall, Columbanus had been forcefully driven out of the kingdom.

After Brunhild’s execution, Clothar II asked the brash Columbanus to come back to Francia. The monk refused, but when he died a few years later, Clothar II promoted his cult. A prophecy was fashioned and stuffed into the dead monk’s mouth: Columbanus had condemned Brunhild as a “wretched woman,” and predicted that Clothar II would rule all of Francia within three years. Clothar had only plotted her overthrow and death to fulfill the holy man’s prophecy.

Another supposed prophecy by the monk was slid into a different work. Columbanus refused to baptize Brunhild’s grandsons because he realized they were cursed: “They’ll never take up the scepters of kings.” The monk and Brunhild are also cast into a battle between good and evil: “The old serpent came to… Brunhild, who was a second Jezebel, and aroused her pride against the holy man.”

“Jezebel” had become a convenient shorthand for how to talk about, and disparage, powerful queens. Jezebel was said to exercise undue influence over her husband, something both Brunhild and Fredegund were accused of doing; Jezebel was reported to be promiscuous, and both queens are accused of taking lovers. Jezebel was killed by being thrown out a window, then trampled by horses. Her body was further obliterated, gnawed on by dogs; what remained of her was spread “like dung on the ground.” Brunhild’s execution was clearly designed to eliminate her in the same way. But Fredegund, despite her prestigious burial, was obliterated as well. All traces of the bold and ruthless queen were scattered to the wind, replaced by those of a placid, devoted mother.

Despite these efforts, the ghosts of Brunhild and Fredegund refuse to stay silent. Bits of their biographies are told slant in myth and legend, in art and literature. They surface relentlessly, determined to be heard.

Even though these queens were absent from my history books, they were in plain sight throughout my childhood as the women I was warned against becoming: the wicked stepmother in my fairy tales, the fat lady singing at the opera, the haughty Jezebel who was preached against in church. And the same strategies used against Brunhild and Fredegund are still being used to delegitimize female power. The Jezebel slur has been consistently deployed against female politicians, from Queen Mary I to Margaret Thatcher and to Vice President Kamala Harris. Women in leadership roles today are forced to ask themselves, between the silence of suppressed history and the oppressive blare of stereotypes, what space remains?

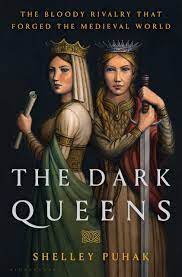

Adapted from The Dark Queens: The Bloody Rivalry That Forged the Medieval World by Shelley Puhak. Copyright © 2022 by Shelley Puhak. Reprinted by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com