With Women’s History Month underway and International Women’s Day approaching on March 8, classrooms and museums across the United States will be focusing on famous women who shaped the world we live in. But not everyone who did so has gotten the recognition she deserved. This week, TIME is telling the stories of women who might have earned the title Person of the Year — a century’s worth of the women who most shaped each year, for good or for ill.

In addition, to shed light on other lesser-known female history-makers, we asked historians to name a woman from the American past whose story should be better known. Here are their picks.

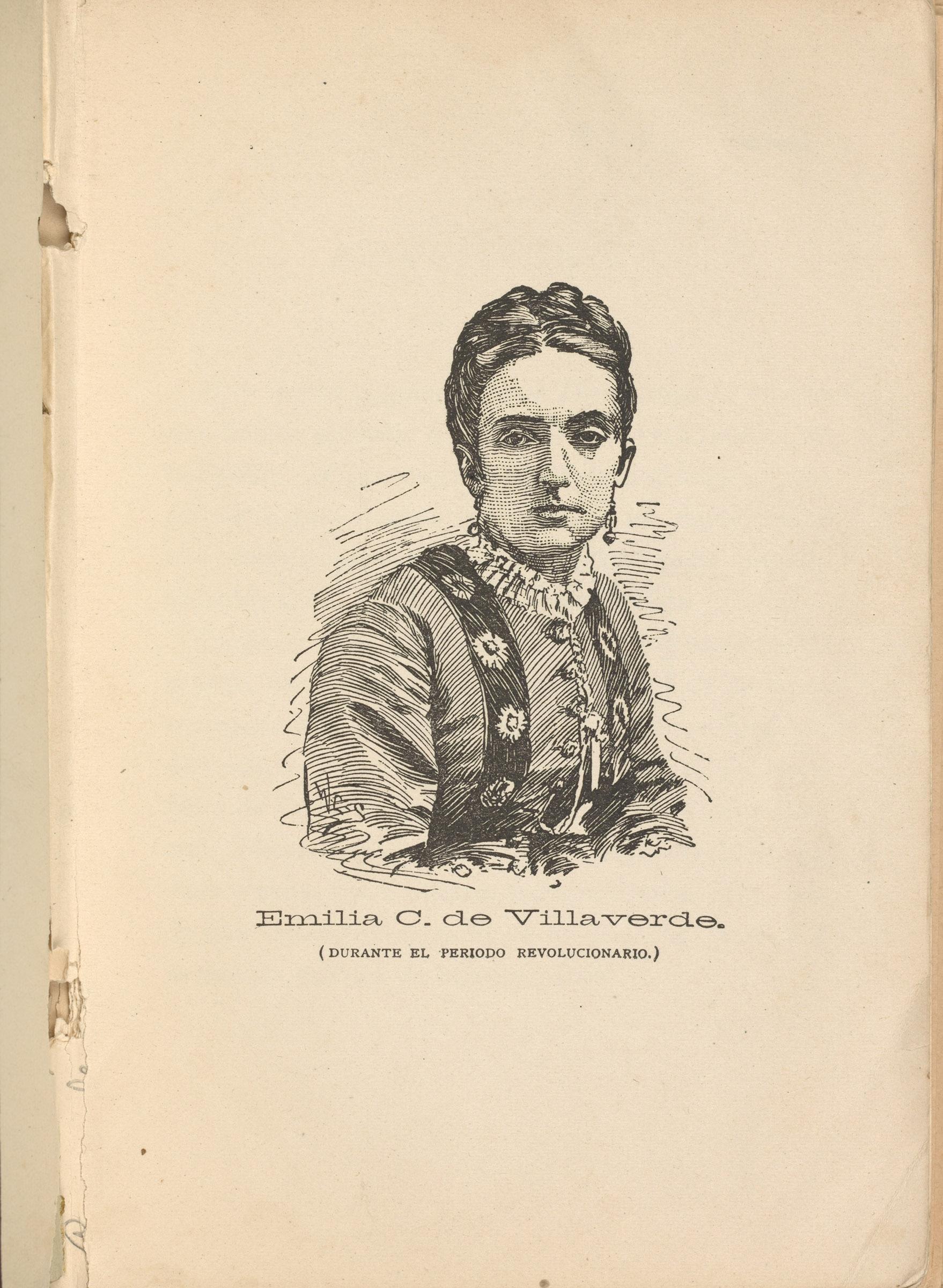

Emilia Casanova de Villaverde

Emilia Casanova de Villaverde is known as a patriot in Cuba, but lived most of her life in New York City. An ardent abolitionist and activist leader, she supported Cuba’s independence from Spain during the last half of the 19th century. As the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878) raged in Cuba, she formed the first women’s club, La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba, to raise funds and sustain the elderly, the widows and orphans who took refuge from the war in New York. She addressed the Congress of the United States about Cuba’s situation, and on several occasions personally sought the aid of President Ulysses S. Grant.

From her baronial coastal mansion in the South Bronx, where a network of vaults concealed the crates of munitions Emilia collected for the liberation army, she organized numerous clandestine expeditions to Cuba. Denounced in the conservative press, ridiculed in political cartoons, and burned in effigy in her hometown, she continued to form women’s clubs for the cause until her death in 1897 — the year before the Spanish-Cuban-American War would change the course of history for Cuba and Puerto Rico.

—Virginia Sanchez Korrol, co-editor of Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia with Vicki L. Ruiz, and Professor Emerita at Brooklyn College, City University of New York

Mary Ware Dennett

She was an artist, suffragist, birth-control reformer and anti-war advocate. She began her reform career at the National American Woman Suffrage Association where she served as literature coordinator and wrote a number of influential essays for the movement. In 1915, she founded the first birth control organization in the United States, the National Birth Control League (later renamed the Voluntary Parenthood League).

She and Margaret Sanger were the leaders of the birth-control reform movement in the 1920s, but her vision of legalizing birth control for everyone who wanted to use it was much more expansive than Sanger’s. Sanger wanted to ensure that birth control remained under the control of physicians and thought medicalizing it was the best path for social acceptance. She successfully quashed Dennett’s vision — birth control as a fundamental right — and today, we know Sanger and not Dennett as a “reproductive rights leader.” But it is interesting to think about how our understanding of contraception and reproductive rights might be different had Dennett prevailed.

—Lauren MacIvor Thompson, author of Battle for Birth Control: Mary Dennett, Margaret Sanger, and the Rivalry That Shaped a Movement and faculty fellow at the Center for Law, Health & Society at Georgia State University

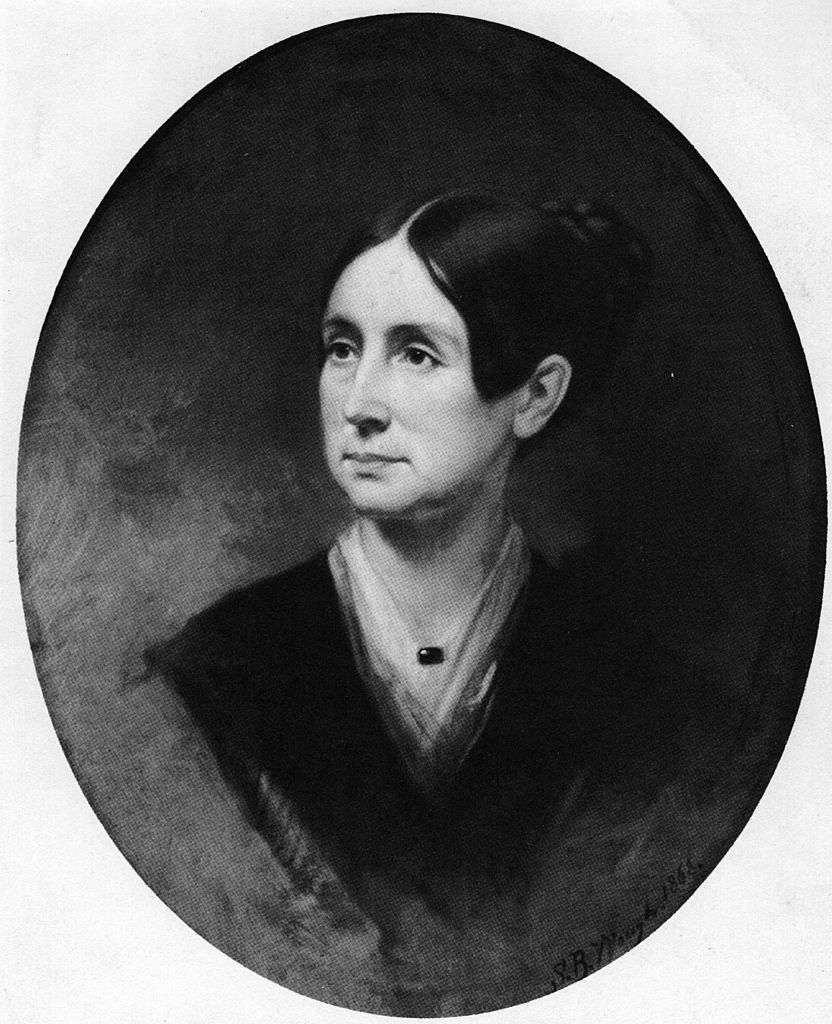

Dorothea Dix

A history-making woman I’m trying to know better is Dorothea Dix (1802-1887). The white Bostonian became internationally known for her activism on behalf of asylum and prison reform, and later leader of Union nurses during the Civil War. She traveled tens of thousands of miles, almost always alone, inspecting prisons, jails, poorhouses and almshouses. The conditions she conveyed in her numerous exposés were horrendous. Local officials purportedly shook with fear when she showed up on their doorsteps demanding admittance. Due to her efforts, every state in the ever-expanding United States allocated land, money and legislative attention to the creation and improvement of insane asylums. Yet despite working with prominent male abolitionists, she remained explicitly racist and resisted abolitionism. The denial of the rights of the institutionalized, the overwhelming ability of husbands to institutionalize their wives as insane, the inequalities of racially segregated asylums, and the published exposés of ex-asylum inmates who sought to bring attention to asylum abuses simply did not exist and/or did not matter in Dix’s world. Like all of us, she’s a bundle of contradictions — but unlike most of us, her contradictions had impact.

—Kim E. Nielsen, author of A Disability History of the United States and Professor of Disability Studies, History, and Women’s & Gender Studies at the University of Toledo

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

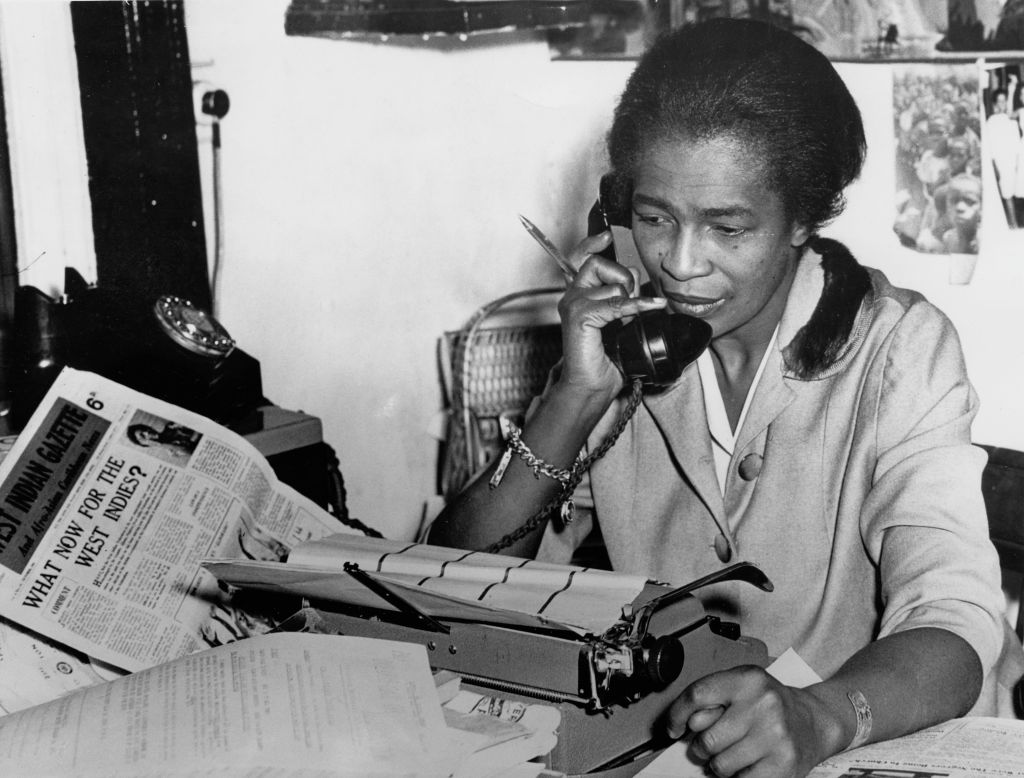

Claudia Jones

Claudia Jones was one of the most influential black radical and feminist intellectuals of the 20th century. Born in Trinidad in 1915, Jones migrated to Harlem during the 1920s and became an active member of the Communist Party. A gifted writer and journalist, Jones worked to broaden Marxist theory by centering women, gender and race. Her groundbreaking article, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” published in 1949, emphasized the triple oppression of race, class, and gender—laying the foundation for what Kimberlé Crenshaw later termed intersectionality.

–Keisha N. Blain, an Associate Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh and President of the African American Intellectual History Society and a W.E.B. Du Bois Fellow at Harvard University

Laura Cornelius Kellogg

Laura Cornelius Kellogg was an Oneida activist, author, orator and policy reformer, and she was one of the founding members of the Society of American Indians (SAI) in 1911. SAI was the first national American Indian rights organization run by and for American Indians. Other organizations believed that total assimilation into American society was the only way to “save” the Indians, but many Progressive Era Indians and members of SAI fought to preserve Native rights and sovereignty. Kellogg was an advocate against increasingly stringent federal Indian policies that, among other things, sent Native children to boarding schools and sought to eradicate Native languages, cultures, and political, economic and social systems. Kellogg left a controversial legacy — one contemporary called her a “cyclone,” while another called her “a woman of brilliance” — but hers is a fascinating story of a Native woman in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

—Katrina Phillips, assistant professor of history at Macalester College and an enrolled member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe

Mary Tape

Little is known of Mary Tape’s life in China. In 1868, the 11-year-old Mary immigrates to the United States and ends up as a servant in a brothel in San Francisco. She runs away and takes shelter at the Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society, where she is raised and takes the name of Mary McGladery. One day Mary meets another young Chinese immigrant, a boy who drives a milk wagon and calls himself Joseph Tape. They marry, and the ambitious Joseph establishes his own prosperous transportation and immigration brokering business.

But the Tapes’ wealth cannot inoculate them from racial discrimination during this time of anti-Chinese exclusion and racial hostility. In 1884, their daughter Mamie is denied admission to a local school because she is Chinese. Mary Tape is incensed. She writes a an impassioned letter and the Tapes sue the principal and the San Francisco Board of Education. They win the landmark case Tape v. Hurley, which guarantees Chinese children the right to a public school education. However, Mamie never enrolls at her local school. After the court decision, the school district builds a Chinese Primary School, “suitable for Mongolian children.” The Tape case and the state’s reaction foreshadows the “separate but equal” doctrine soon to become law in the 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson.

—Renee Tajima-Peña, Series Producer of the upcoming PBS series Asian Americans and a Professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles

Mamie Till-Bradley

Photos of the badly disfigured corpse of Emmett Till — the Chicago 14-year-old lynched while visiting family in Mississippi in August 1955 — rocked the globe, but we wouldn’t have seen any of those images if his mother hadn’t insisted on an open-casket funeral for him. She was an everyday black woman who had been confronted with this horrific tragedy, and made a crucial decision that helped to set off this movement. She had to go through so many hurdles, calling on politicians to help her re-claim his body; they were ready to just quickly bury her son to cover the whole thing up, but she wanted to expose the brutality. Emmett Till’s death and those images were a spark that finally set the civil rights movement ablaze. In spite of death threats, Mamie Till-Bradley then went on a speaking tour to raise awareness about her son’s death. Even after they are denied justice — Till’s killers were acquitted — she continued to be an activist.

—Kali Nicole Gross, Martin Luther King, Jr. Professor of History at Rutgers University and co-author of A Black Women’s History of the United States with Daina Ramey Berry.

Maggie Lena Walker

Maggie Lena Walker played an important role in making Richmond the cradle of black capitalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Walker is best known as the first black woman bank president in the United States. She organized and led the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank from its founding in 1903 to her death in 1934. The bank was part of her vision for the Independent Order of St. Luke, a secret society founded in the 1850s by a free woman of color. The IOSL and St. Luke Bank formed the foundation of a financial powerhouse that, at its height in the 1920s, provided financial services to 100,000 members and others in more than 20 states. Before the Great Depression, the IOSL was arguably the largest employer of professional, white-collar black women in the country. Walker battled public misfortune and private pain in a life lived in the public eye. In 2017, the city of Richmond dedicated a memorial statue of Walker on Broad Street. Walker’s memory endures as a staunch crusader for black economic and political rights, especially for black women.

—Shennette M. Garrett-Scott, Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Mississippi and author of Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal

Jane Cooke Wright

A physician and researcher, Jane Cooke Wright is credited as having been among the cancer researchers to discover chemotherapy. She was the daughter and granddaughter of African American physicians. In 1964, Wright was the only woman among seven physicians who helped to found the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and in 1971, she was the first woman elected president of the New York Cancer Society. Wright was appointed associate dean and head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department at New York Medical College in 1967, apparently the highest ranked African American physician at a prominent medical college at the time, and certainly the highest ranked African American woman physician. She was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to serve on the National Cancer Advisory Board (aka the National Cancer Advisory Council) from 1966 to 1970 and the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke from 1964 to 1965.

—Martha S. Jones, the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History at Johns Hopkins University and the author of the forthcoming Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com