I always take note of pictures of women who are not flashing a camera-ready grin.

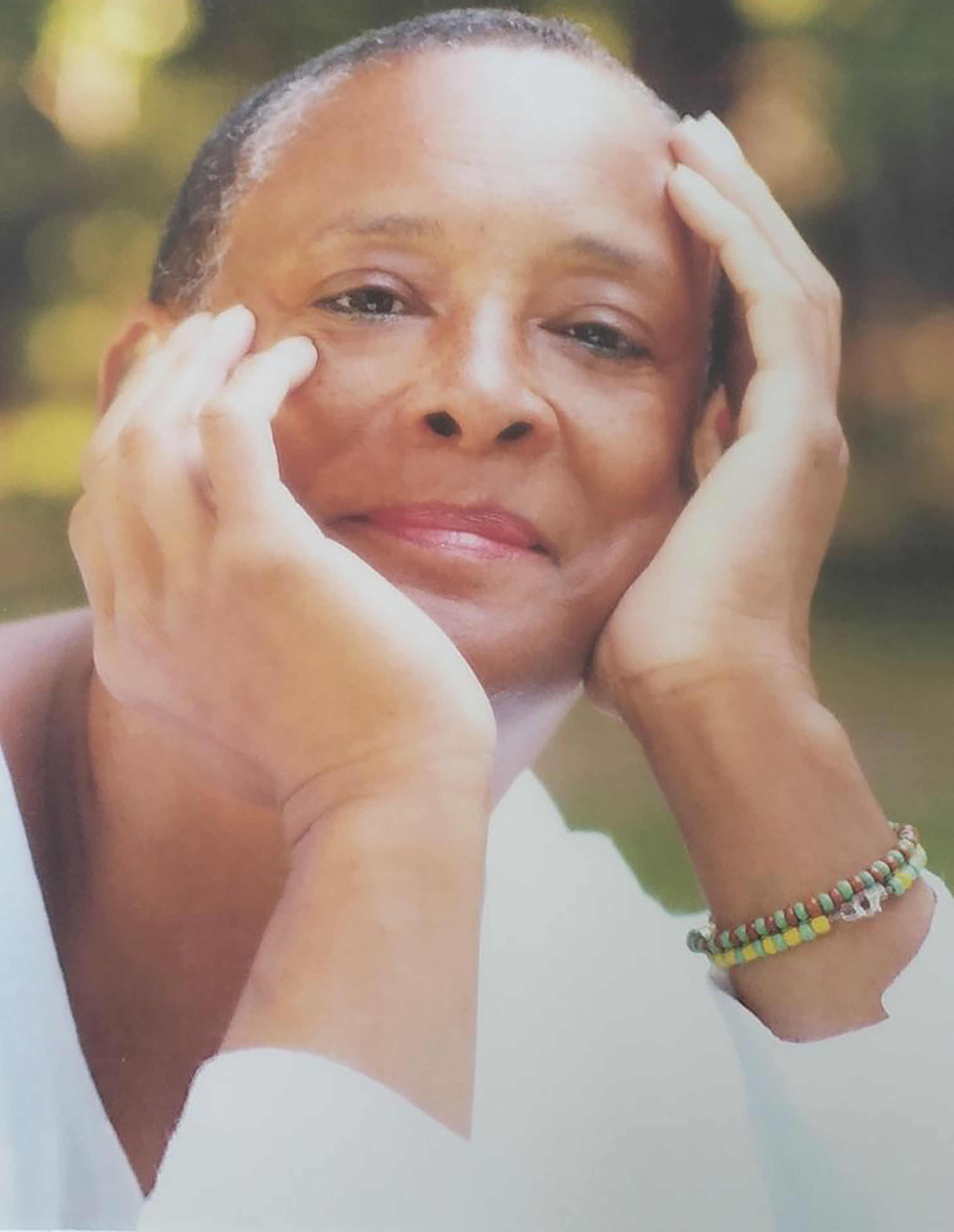

They make me wonder what such a woman has done with her life that it need not be rendered more palatable with a big, uncomplicated toothpaste-ad smile. So the first photo I saw of Claudia Booker—the one the people who loved her selected for her obituary when it ran nearly two years ago—held my attention from the beginning.

As I explored the life of Claudia Booker, who died on Feb. 19, 2020, at 71—after careers as a teacher, a community activist, a lawyer, a Carter Administration staffer, an administrative judge, and, finally, a doula, childbirth educator, and midwife—I found not simply the story of a woman with a remarkably agile mind. A few days before she died, Booker texted another Black birthworker, one of the women into whom she’d poured so much of what she knew, that she was getting better. She texted about the babies she was going to catch, the mothers she was going to calm. Booker had no plans to rest or sit down, her daughter Canida Azulai Booker told me. But Claudia Booker died anyway, struggling to breathe and suffering through what she believed was the flu. Her body was ravaged by cancer but, with her death coming as the pandemic just began to grip the United States, those who know her tell me they still wonder if she fell to an early case of COVID-19.

As the world edges towards the end of a second year of disruptions and distancing and death caused by a global pandemic—even if Booker’s demise can’t be confirmed to be among its impacts—the loss felt by those who loved her has been sadly shared by people around the world. But, in the United States, it has not been equally distributed. Due to disparities long unaddressed, Black, Latino, and Native American patients have been considerably more likely to be infected or die from COVID-19. So, for these Americans, layered sadnesses hang particularly heavy.

When a person dies, they often take with them much of what they knew, what they have seen and what they have felt. If they are fortunate, there is time to pass at least some of it on. In a pandemic, mass unprepared-for death is so common that knowledge loss also becomes part of the pandemic’s toll. Eyewitness accounts of the civil rights movement go un-gathered. Recipes passed down through the generations but never written down will never be cooked again. Claudia Booker’s know-how can no longer help a new generation of midwives—even as a growing body of research and reporting suggests that Black birthworkers like her could be a key path to addressing racial disparities in pregnancy-related complications and death. As we mark Black History Month, we know that a critical part of that history has, in these last few years, been lost.

The loss is all the more staggering when one considers that oral history has for Black Americans always been essential.

As the American way of enslaving Black Americans developed, many states enacted laws specifically barring slaves from learning to read or write. People who are not allowed to read and write don’t leave behind journals and letters or many other documents, explains Kelly Elaine Navies, a museum specialist and oral historian at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Oral history has been a key tool to fill gaps in the “official” history.

Read more: I Searched for Answers About My Enslaved Ancestor. What I Found Was More Questions

Today, while the written record of Black American life has grown and continues to do so, oral history maintains a special place. The information it can convey remains unique and valuable. That’s why the Smithsonian has made available online a detailed guide for collecting oral histories, a place to share some materials with the museum as well as information about the particular importance of and ideal way to gather Black stories.

More from TIME

“Oral history can tell us things that written records often cannot,” Navies says. “Not just when something happened or that someone was at a certain place but how did they feel about it? What part of that experience was most important, so important that they actually remembered it?”

The experiences of the last two years will be essential to an understanding of Black life and Black history in the United States in the early 21st century, but the museum can’t collect it all. Navies wants us to take up this work in our own families and local historical societies. “Historians will be looking at this period for years to come,” she says. “I would really advise everyone to spend some time recording their elders.”

But, she acknowledges, it’s already too late for many of those stories to be collected.

Twice last year, while working on various stories about race, I learned that sources under the age of 50 had, in a matter of weeks, died of COVID-19. The loss of American life is now measured in the hundreds of thousands. What was held in those minds is less easily tallied.

This Black History Month, the NMAAHC anticipates sharing the stories and work of Black women who have worked as birth doulas. Navies herself did her graduate work gathering oral histories from Black midwives in the South. All of that made me think of the remarkable things I’ve been told about Booker, and how she lived and died. Booker’s story is, in many ways, a quintessentially American one—and the history of Black midwifery offers a valuable lens on the country’s history.

Prior to the 20th century, midwifery was often a tradition passed from mother to daughter and regarded not as a job, but a calling, says Jenny Luke, who trained as a nurse in England before becoming a historian of midwifery. Especially throughout the American South, Black “granny midwives”—women who are today often referred to in birthworker circles as Grand Midwives in recognition of their expertise—were part of the health care infrastructure. They provided not just physical care at the time of a birth but also whole-person care that mothers can sometimes feel is missing in a hospital setting, Luke tells me. But in the 20th century, amid a gradual but intentional squeezing out of midwives by doctors, hospitals and federal law in the 20th century, “lay midwifery became associated with poverty, being Black and uneducated, being rural,” says Luke.

Read more: I Was Pregnant and in Crisis. All the Doctors and Nurses Saw Was an Incompetent Black Woman

As their work was relegated to the shelves of history, lay granny midwives—mostly Black women—were the subject of books and ethnographies; Luke’s Delivered By Midwives is a detailed history. But in their practice, Black birthing traditions were in danger of being lost until a movement of Black women, driven in large part by grim statistics about Black maternal and infant mortality, began to foster their resurgence. In 2005, Booker became one of those women, starting the process to become a certified professional midwife.

“Becoming a midwife is something that happens gradually over time to you,” Booker said in a 2010 interview published in the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) newsletter. “It is something we grow into. It is the journey of birthing a midwife—you have to sit, reflect, and simmer in ‘being with women.’”

When Booker—a fierce advocate for birth justice—took Black birthworkers under her wing, she insisted that they too obtain both a combination of modern training and an understanding of Black birthing traditions that had been passed down through generations. When she celebrated a period of remission in 2019 by hosting a training, it covered not just modern prenatal care techniques but also post-birth rituals that for thousands of years have helped Black mothers heal and babies thrive, says Taiwo “Tia” Ikeoluwa Adeloye-Ajao, an attendee who is a registered nurse training to become a midwife.

Booker bequeathed her midwifery bag and instruments to Alaina Snell-Broach, a doula and midwife-in-training. But the passing on of what Brooks knew was cut painfully short.

Birthworkers like Booker often say that the people in the room when a midwife catches a baby are never alone. In that moment when the veil that separates the living and the dead is at its thinnest, the ancestors are in the room, sharing their support and, when needed, their wisdom.

Not too long after Booker died, Tamoyia Ragsdale-Hashim, the owner and operator of Rise Birth and Postpartum services in Prince George’s County, Md., was assisting at a birth with a mother who had worked with Booker for her previous two births. Ragsdale-Hashim says she could hear her predecessor’s voice, giving her instructions, encouragement, and, in that special Claudia Booker way, admonitions that she could do this or it was time to do that. Ragsdale-Hashim asked if anyone else in the room was also hearing “Ms. Claudia.” The mother and father said they too felt her presence and her voice in their heads.

“I was so sad, angry. I was like, ‘Why now? I didn’t have enough time,’” Ragsdale-Hashim says of her feelings just after Booker died in February 2020. “The wealth of knowledge that not only went with her, but [that] she also left here is immense.”

The more I learned about Booker, the more I was reminded how essential it remains that the stories of people like her are captured and preserved, that the knowledge they had is passed on. Some of this history is gone forever. Some of it, with each passing day, is intentionally suppressed. But, experts like Navies say, those of us who remain can still mitigate the damage. Press record on one of our many devices. Lean away from selfies and into capturing now what we see, think, and feel. Ask others questions. Remember what we learn.

— with reporting by Simmone Shah and Julia Zorthian

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com