Kendra Levine’s son, Eddie, is only 5 years old, but he immediately recognized the significance of the negative result on the COVID-19 rapid tests he took at home last weekend.

The tests, which were provided by the Berkeley Unified School District in California before students left for winter break, meant Eddie could return to school and see his friends again after two weeks away. Best of all, they meant Levine could send him to school on Monday with more peace of mind.

“He was extremely thrilled to show it to us,” says Levine, whose son has become familiar with pandemic routines in the last two years. “For two years, most of his memory has been shaped by this. ‘We have to wear masks, we have to avoid people who aren’t wearing masks,’” she says. “The thing we keep telling him is: We’re doing our part to keep other people safe.’”

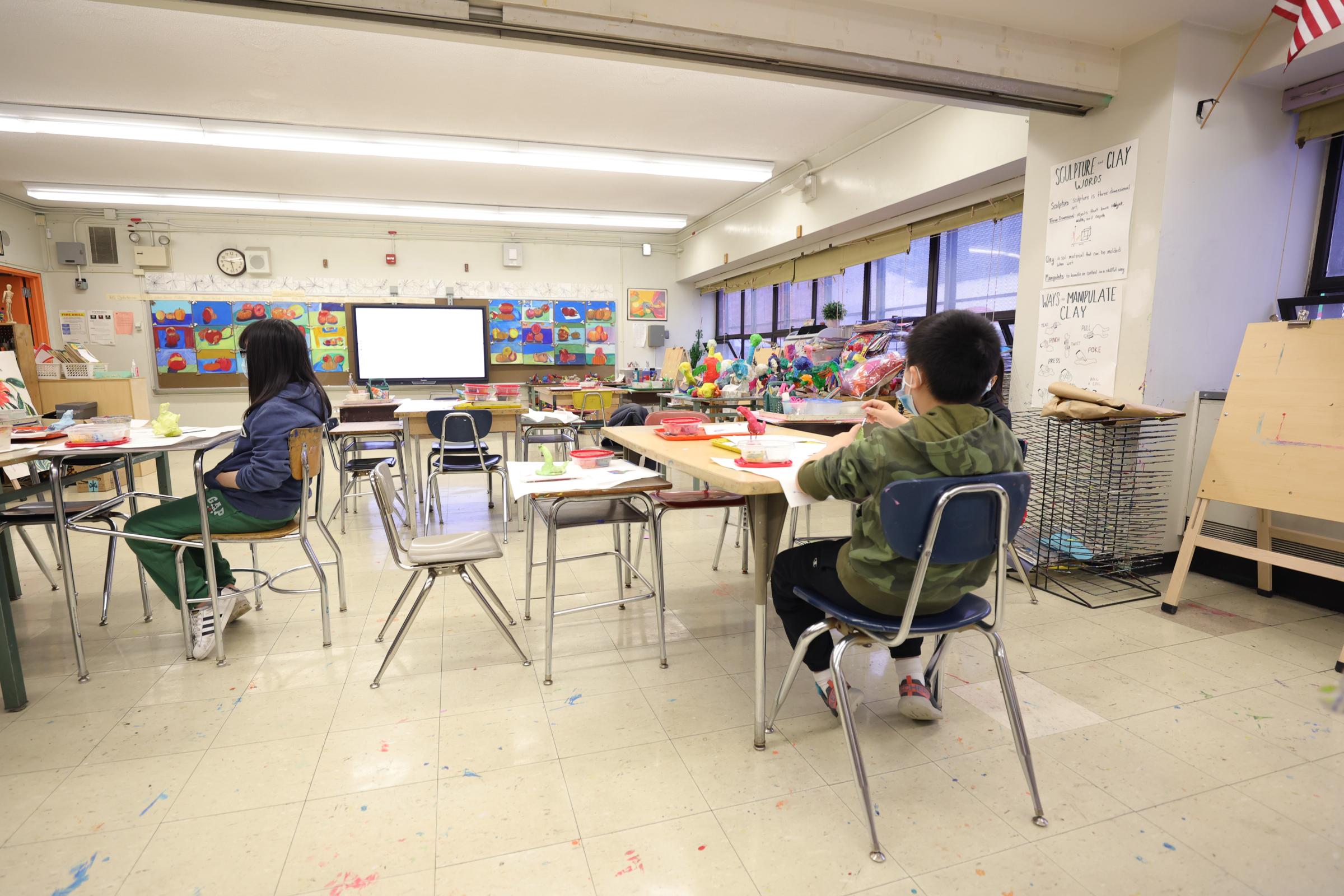

Students are returning from winter break this week as COVID-19 cases fueled by the Omicron variant surge, complicating efforts to keep school buildings open and students and staff safe. Some districts are requiring students to show proof of a negative test. Others, facing staff absences and high infection rates in the community, have shifted back to remote learning.

Read more: CDC Director Rochelle Walensky Faces a Surging Virus—and a Crisis of Trust

The overall picture is one of confusion for parents, children and school staff as they try to adjust to what is shaping up to be another semester dominated by pandemic concerns. For every family with access to home tests, there are countless others facing school closures or scrambling to find COVID-19 tests on their own in hopes of sending their kids back to class.

All 51,000 public school students in Washington D.C. were required to submit proof of a negative COVID-19 test on Wednesday, before classes resumed Thursday. In New York City, where the new mayor, Eric Adams, vowed to keep schools open, officials increased random in-school testing and said they will provide at-home rapid test kits to every student and staff member in a classroom where someone tests positive.

California leaders had pledged to provide the state’s 6 million K-12 students with at-home COVID-19 tests, anticipating a virus spike during winter break. But by the time many schools reopened on Monday, only about half of those tests had been delivered to districts, the Los Angeles Times reported.

When Minneapolis Public Schools emailed families on Dec. 30, asking them to “take the extra step of getting tested for COVID-19 before returning to school on Jan. 3,” parent and epidemiologist Rachel Widome says the “Covid Test Hunger Games” began, as parents shared tips in Facebook groups for finding rapid tests at drug stores. The district shared a link to community testing locations, but many were overwhelmed by long lines.

Even in places like Berkeley, where tests were provided, many families did not report results. The district distributed test kits provided by the state to roughly 12,000 students and staff, asking them to test on Dec. 31 and again on Jan. 2. About 64% (7,687 people) reported their test results, revealing nearly 230 positive cases, a positivity rate of 2.95%.

Read more: The Achievement Gap is ‘More Glaring Than Ever’ for Students Dealing With School Closures

Still, that was enough to reassure the district superintendent, Brent Stephens, who says those positive results enabled district leaders to minimize viral spread in schools and allowed those who’d tested positive to isolate safely.

Stephens hopes those take-home tests—combined with regular in-school testing, mandatory masking and required COVID-19 vaccination for those age 12 and over—will help keep buildings open for students.

That’s critical to preventing even more of the learning loss and social stresses that became clear during extended school closures in the 2020-21 school year, he says.

“It is where they belong. It’s where they need to be. It’s where they can grow up. We did see just extremely negative effects of that prolonged period of distance learning showing up in terms of depression, mental health issues, feelings of isolation, lost opportunities for development,” Stephens says. “We all feel a very strong commitment, as a community, to keep schools open and to be sure that students aren’t deprived of those critical experiences again.”

But rising COVID-19 cases have made that challenging for districts around the country. Stephens says staff absences in his district reached “a level we’ve never seen” this week, with 65 staff members absent Tuesday and only about 25 substitutes available to fill in. The district is considering sending office staff who are certified to teach into classrooms to cover those absences.

In Chicago, officials canceled school on Wednesday and Thursday as members of the teachers’ union voted not to report to school buildings and called for remote learning amid surging coronavirus cases, asking the district to expand COVID-19 testing before they return.

But a testing shortage remains a nationwide obstacle.

Widome, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota whose 4th-grade son attends Minneapolis Public Schools, had purchased rapid tests already and had some at home, but she knows she’s an exception.

“For a lot of families, that’s probably an impossible ask, given the testing shortage,” Widome says. “There’s certainly infectious people who are in schools now —both students and staff— that, had they had access to a test, they wouldn’t be in school right now. And those are situations that could be starting new chains of infection.”

President Joe Biden has pledged to improve testing availability and announced a plan to distribute 500 million free at-home, rapid test kits to Americans. But school resumed this week without those reinforcements.

“This should be easy. You shouldn’t have to spend time and money and intellectual energy and be a well-connected person to be able to access these tests,” Widome says. “We need to make it easy for individuals to do the right thing. We need to make it easy for people to get tested. And right now we’re making it really hard.”

Widome counts every day her son spends in school as a victory, but even though he’s vaccinated and good at wearing a mask, she worries about the risk that he’ll still contract COVID-19. And she’s frustrated that the simple act of sending her child to school remains so fraught nearly two years into the pandemic.

“I have a certain amount of resentment that I and other people are in this situation, that leadership has let us down so much that two years in, I have to worry about sending my kid to school,” she says. “I would’ve thought we could’ve been in a better place by now.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com