Stengel is the former Editor of TIME, an MSNBC analyst and the author of Information Wars: How We Lost the Global Battle Against Disinformation.

On the day Nelson Mandela was released from prison in February of 1990, he walked out of the gates of Victor Verster prison in Cape Town and was surprised by the crowds of people. After striding out and giving the clenched fist salute, he got into a car to go to the Grand Parade in Cape Town where he was scheduled to give his first speech as a free man. But the driver was upset by the crowds and panicked, and then started driving wildly. Twenty minutes later, with the eyes of the world upon him, and a 100,000 people waiting to hear him, the planet’s most famous freedom fighter was lost. .

Mandela told me this story in 1993 while we were working together on his autobiography. He said that he had managed to calm the driver down, and get him to stop at the house of an ANC supporter outside of town. But then he wasn’t sure what to do. “Whilst we were there,” Mandela said to me, “Tutu phones and said, ‘Man, you must come immediately to the town hall because the people are going to rebel if you are not here!’ So I went.” Mandela recalled this with a smile and a laugh, but he always listened seriously to the man everyone called The Arch. After his speech that day, Mandela spent his first night of freedom at Tutu’s home at Bishops Court in Cape Town. “He is one of my heroes,” Mandela told me, and meant it.

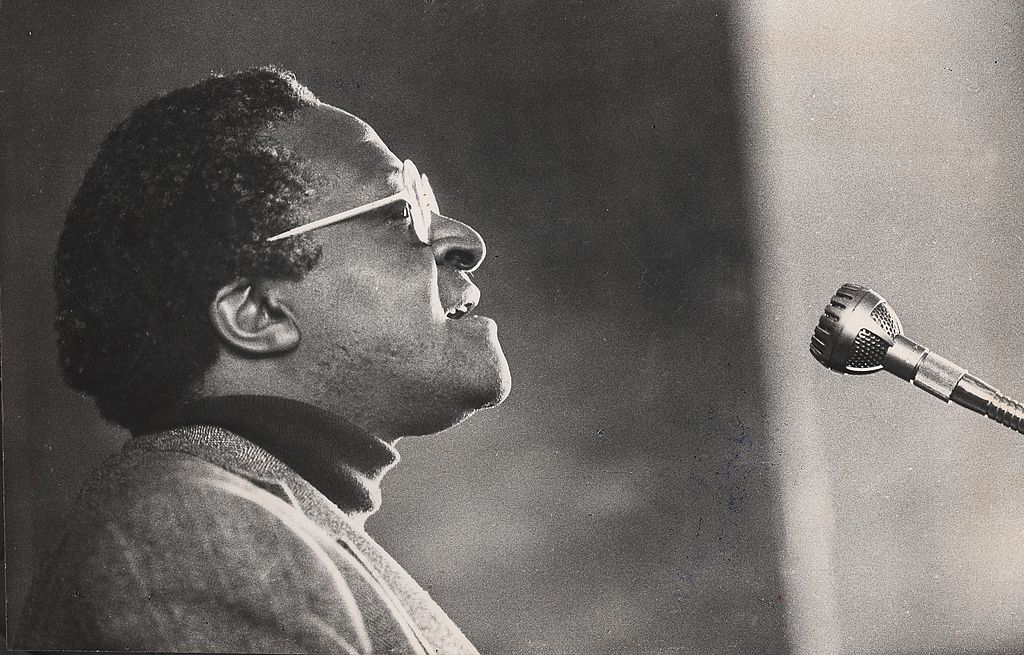

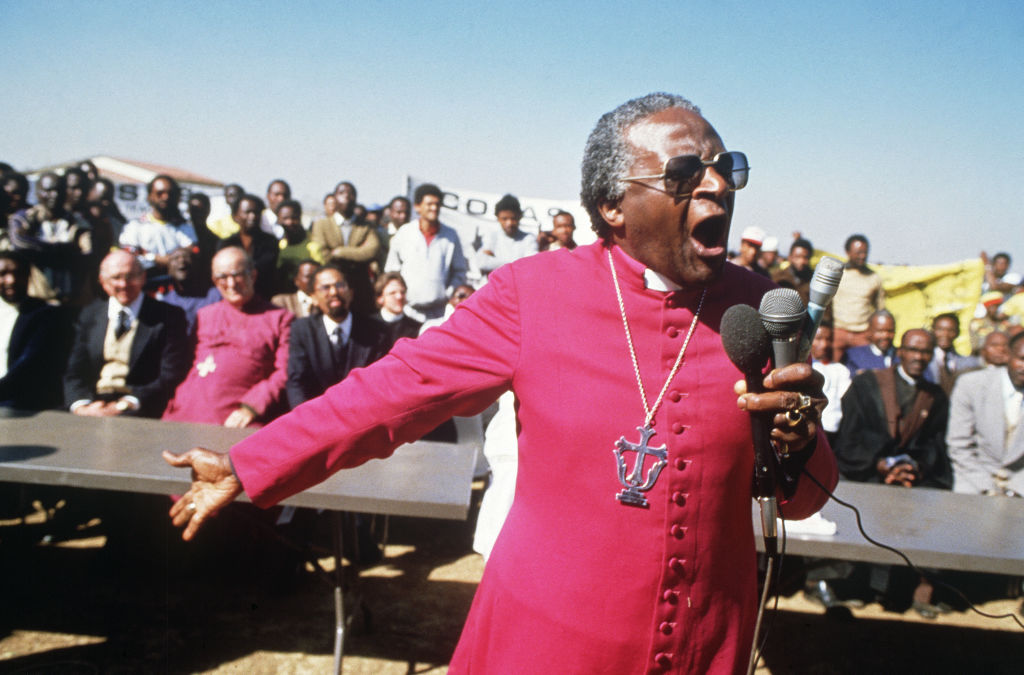

Desmond Mpilo Tutu, who died this week of cancer at the age of 90, was the ebullient hero of the struggle against apartheid and the quest for freedom in South Africa. The son of a schoolteacher and a domestic servant, he became the head of the Anglican Church in South Africa and a tireless and courageous campaigner against what he called the evil of apartheid. Martin Luther King Jr. once described himself as a “drum major” for justice—Tutu described himself as a “rabble-rouser” of righteousness. He is one of the handful of those who can be called South Africa’s greatest generation: Mandela, Sisulu, Tambo, Kathrada, and Tutu. He was a powerful and fearless beacon of moral justice and perhaps the most spellbinding speaker I’ve ever seen. His voice ranged over octaves, from squeals of laughter to a basso profundo of moral righteousness, from whispers of prayer to shouts of joy. When the spirit moved him—which was often—he would do a Hobbit-like dance on stage. I’d never really understood the phrase “infectious laughter” until I heard him speak. His goal was never changing: to mobilize people against injustice but always, always toward forgiveness and love. In the face of so much injustice and despair, he never lost his faith, and never failed to inspire it in others. There may be no atheist in foxholes, as the saying goes, and there were very few in the audience after Tutu spoke.

I first met Bishop Tutu in the 1980s when I went to South Africa to write a book about apartheid in a small Transvaal town, but I did not spend much time with him until I started working with Mandela. Then, I often sat with him while watching Mandela speak. I once joked with him that I told Mandela he must always speak before Tutu, rather than after, because Tutu was so much of a better speaker. Tutu laughed—but he saw his role as one of Mandela’s apostles. Tutu understood something about Mandela that few did. He once said that prison can do one of two things to people: it can make you harder and more bitter, or it can make you stronger and, paradoxically, more compassionate. He said that’s what happened to Nelson Mandela. He was right. In 2010, I interviewed Tutu in Cape Town during the World Cup as part of the TIME and Fortune CEO summit. We spoke before going on stage, and even though the Arch was already suffering from the cancer that would eventually take his life, his only questions for me were about Mandela’s health.

More from TIME

On the day that Mandela came out of prison, Tutu said he could now die a happy man. He had carried the baton for at least a decade before handing it to Mandela. In the 1980s, when Mandela was still behind bars and South Africa was a cauldron of anti-apartheid revolt and violence, Tutu was the face of resistance. He was 5’4” tall and spindly, but he would skip up the steps to the stage in his magenta shirt with the white collar while ranks of white policemen with automatic weapons looked on. He was afraid like any sane person would be, but he believed he had no choice. He was arrested in 1980, and he spoke out for sanctions against the white apartheid government, something that did not endear him to the white National Party. He was always resolutely against violence, whether it came from the white government against Black protesters, or Black protesters against whites or someone from their own ranks they regarded as a traitor. In the 80s and 90s, he would sometimes wade into a crowd of angry Black protestors to rescue someone the crowd had attacked for being a spy. At the gigantic funeral for the victims of the Boipatang Massacre in 1992—when government security forces killed more than 40 people—Tutu turned the crowd’s anger into prayer. “We hate violence from whatever quarter,” he said.

Mandela always made a distinction between people who believed in non-violence as a principle rather than a tactic. In that former category, he put Gandhi and Tutu. He himself supported non-violent protest when he was a young man, and then abandoned it when he saw that it was not going to help him achieve freedom for his people. But he admired those like Tutu who would not renounce it. Tutu, for his part, understood Mandela’s own embrace of violence and would not criticize him for it. “I am a man of peace,” Tutu said, “but not a pacifist.”

He won the Nobel peace prize in 1984, a rare moment of prescience by the Nobel Committee in Sweden. This both protected him and gave him a global platform. He used it. That same year, he bluntly criticized President Ronald Reagan’s so-called policy of “constructive engagement” with the white apartheid regime. In a letter to the U.S. Congress he wrote, “You are either on the side of the oppressed or on the side of the oppressor. You can’t be neutral.” He never was.

Tutu said again and again that he was not a politician. But of course, he was shrewdly political. In 1994 after Mandela became president of South Africa, he made Tutu the chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a national tribunal to try to expiate the sins of apartheid. This was tricky terrain and Tutu navigated it with grace. At televised sessions where you could hear Black women talking about how their children had been brutally murdered and white former security police confessing to their own nightmarish crimes, you could often see Tutu weeping. He knew the Commission had to be about more than punishment and revenge. “Without forgiveness,” he said at the time, “there is no future.” The Commission’s final report was an indictment of the apartheid regimes horrors, but it also included a section that criticized the ANC for human rights violations. The ANC, now in power, attempted to block the report’s release. Tutu ignored it. “I didn’t struggle in order to remove one set of those who thought they were tin gods,” he said, “to replace them with others who are tempted to think they are.”

Tutu was the enemy of injustice wherever he saw it. He criticized Mandela’s successor Thabo Mbeki for ignoring the AIDS crisis. He criticized Mbeki’s successor, Jacob Zuma, for corruption, calling his rule “disgraceful.” He criticized Zimbabwe’s president Robert Mugabe for oppressing his own people. He criticized the African Anglican Church’s refusal to endorse gay priests and same-sex marriage, saying “I would not worship a god who is homophobic.” He hated only one thing: injustice. More than anyone I’ve ever seen, he seemed truly touched by God. He dubbed South Africa the “rainbow nation of God” because he said it was a model for the rest of the world. In the last few years, he seemed to relish the prospect of leaving the earthly stage. In a final interview with the Associated Press for what would be his obituary, he was asked how he wanted to be remembered. Here’s what he said: “He loved. He laughed. He cried. He was forgiven. He forgave.” Amen.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com