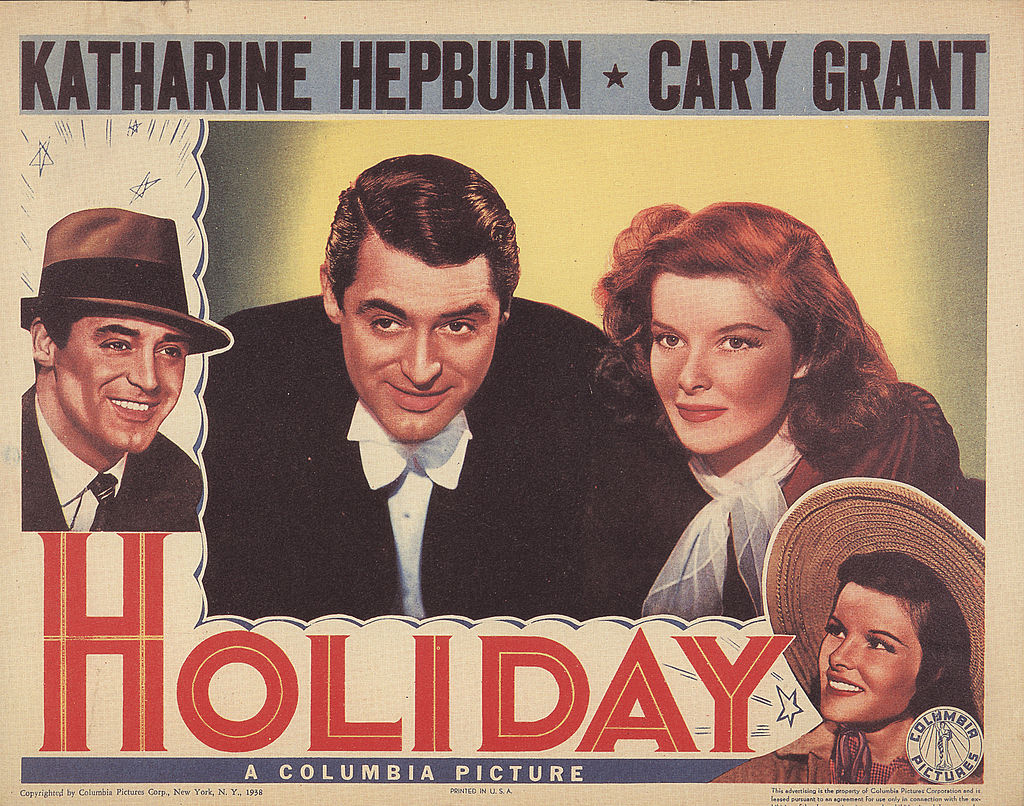

The divide between people who claim to love New Year’s Eve and those who loathe it is perhaps not as wide as you’d think. Even if you strive to view the midnight countdown as a time of fresh beginnings, it’s human to be at least slightly haunted by the specter of everything you failed to accomplish in the previous 12 months, of all the things that went wrong despite your best hopes. The best medicine for those who find New Year’s Eve depressing is to simply acknowledge it as a time of wistfulness. And for that mood, there’s a perfect movie: George Cukor’s 1938 Holiday, starring Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant.

Holiday is a joyous movie that nonetheless comes with a pang trailing along, like a comet’s tail. Grant plays Johnny Chase, a charming bachelor with a floppy forelock but a firm plan: He’s a stockbroker who’s been working since he was 10, and he’s saved a little money. Now he just wants to enjoy life while he’s got the verve and energy to do so. He’s not anti-work—he’s willing to go back if or when he needs to. But for now, as he puts it in an impassioned speech whose rhythms have a “Song of Myself” exuberance, “It’s always been my idea to make a few thousand early in the game and then quit for as long as it lasts, and try to find out who I am and what goes on and what about it, now, while I’m still young and feel good all the time!”

Johnny has fallen in love with New York heiress Julia Seton (Doris Nolan), who’s cool and beautiful and who seems like fun, kind of. They’ve become engaged after a whirlwind romance, and she has no idea of his hopes and plans. Her expectation is that he’ll go into finance, like her uptight father (Henry Kolker); for her, the privilege of having money is a hamster wheel she’s happy to stay on.

When Johnny pays his first visit to the Seton mansion, he meets Julia’s sister, the eccentric livewire Linda (Hepburn), who adores her sibling and grills Johnny ruthlessly about his intentions. As witnesses to this conversation—the verbal equivalent of cartoon squirrels racing to keep up with one another, their tails flicking with joy at having met a kindred spirit—we see these two are perfect for each other. Julia hasn’t even appeared on-screen, but we know she’s all wrong.

The pivotal scene in Holiday takes place during an opulent New Year’s Eve party, held at the Seton mansion, during which Johnny and Julia are set to announce their engagement. Linda has not made an appearance at the party: she had been hoping to hold a small family gathering to celebrate Julia and Johnny’s engagement, but her wishes were overruled by her sister and her father, as, it becomes clear, they always have been. Linda has sequestered herself in the playroom upstairs, the room most beloved by her late mother, and the only place in this otherwise soulless dwelling where Linda and her depressed, perennially sozzled brother, Ned (Lew Ayres, in a performance that’s partly funny, but more often wrenching), feel truly at home.

The people who truly matter in this story gradually find their way to this room. The first to arrive are Johnny’s dearest friends, Professor Nick Potter (the great Edward Everett Horton) and his wife, Susan (the also great Jean Dixon), also presumably an academic. We’ve met this couple earlier, in the movie’s first scene: They live in a tiny apartment with cozy chairs for reading and tables stacked with books; they’re the kind of couple who, you imagine, never run out of things to talk about. For Johnny—and maybe for many of us watching—they’re the gold standard, an ideal of what married life can be.

Nick and Susan don’t fit in at the Seton mansion; that’s clear the moment they arrive at the party, in evening clothes that may be a year or two out of date but are still perfectly serviceable. They find their way to the playroom, accidentally. Linda, miserable and unyielding, greets them warily, but snaps out of her funk when she remembers that Susan had once given a guest lecture at her college. Ned, hiding from his father with the only true comfort he knows, a highball glass, is also a part of the playroom club. And eventually, Johnny shows up there too. It’s there that Johnny and Linda’s fate is sealed—only they still can’t see it.

Holiday is one of the four movies Hepburn and Grant made together, and the second one they made in 1938. (The other is the classic Howard Hawks’ screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby.) Like the final film they’d make together, The Philadelphia Story (1940), Holiday was adapted from a play by Philip Barry, best known for dramatizing the foibles of the rich. Even so, Holiday is much more than a story highlighting the stark differences between the haves and the have-nots. More accurately, it rushes head-first toward a set of haunting existential questions: What do you want out of life, how do you get it, and whom do you want to be doing it with?

Read more reviews by Stephanie Zacharek

The most famous clip from Holiday shows Grant (formerly part of a touring acrobatic troupe and thus an expert tumbler) and Hepburn executing a marvelous his-and-hers somersault, a leap of faith that, like marriage, demands both trust and a sense of humor. The Potters, and Ned, look on, delighted. But just as Johnny and Linda finish their fabulous feat—the whole trick lasts about 40 seconds, but you’ll remember it forever—the spell of their just-before-midnight happiness will be broken, albeit only temporarily. And when that break happens, the vulnerability on Hepburn’s face is shattering. Linda, with her sharp wardrobe and even sharper cheekbones, may seem invincible, but we know she’s not.

Johnny knows what he wants, but he’s on the wrong path to getting it. Linda doesn’t know what she wants, but she does know her current life can’t provide it for her. By the film’s end, these two find their way to one another, as we knew they would. They’ll live a life of books and art and music, of travel and adventure, of never running out of things to talk about. In their classic Hollywood happy ending, they’ll have everything they ever wanted, which is everything we want for them too.

But even so, there’s something about Holiday that tugs at you—maybe because even the most happily coupled-off people know that nothing is ever perfect, and those who are alone can’t help wishing they could experience some of that imperfection. New Year’s Eve is a turning point for Linda and Johnny, a dual somersault toward the possibility of happiness. And every time I watch them flip and tumble through the air, both landing on the floor in a graceful, orchestrated roll, I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. So I do a little of both.

More from TIME

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com