When Steven Spielberg approached the playwright and screenwriter Tony Kushner about the possibility of remaking West Side Story in 2014, Kushner was initially apprehensive for several reasons. For one, he had impossibly large shoes to fill: the musical, created in 1957 by artistic titans—director-choreographer Jerome Robbins, composer Leonard Bernstein, lyricist Steven Sondheim and writer Arthur Laurents—is a revered classic and a pillar of 20th century American art. At the same time, there are many aspects of the musical that seem severely outdated to a younger, more culturally conscious audience. Many debates have erupted over the years about the musical’s brownface origins and cartoonish depictions of its Puerto Rican characters. Last year, the Puerto Rican writer Carina del Valle Schorske called for the musical to be retired in a New York Times piece titled “Let ‘West Side Story’ and Its Stereotypes Die.”

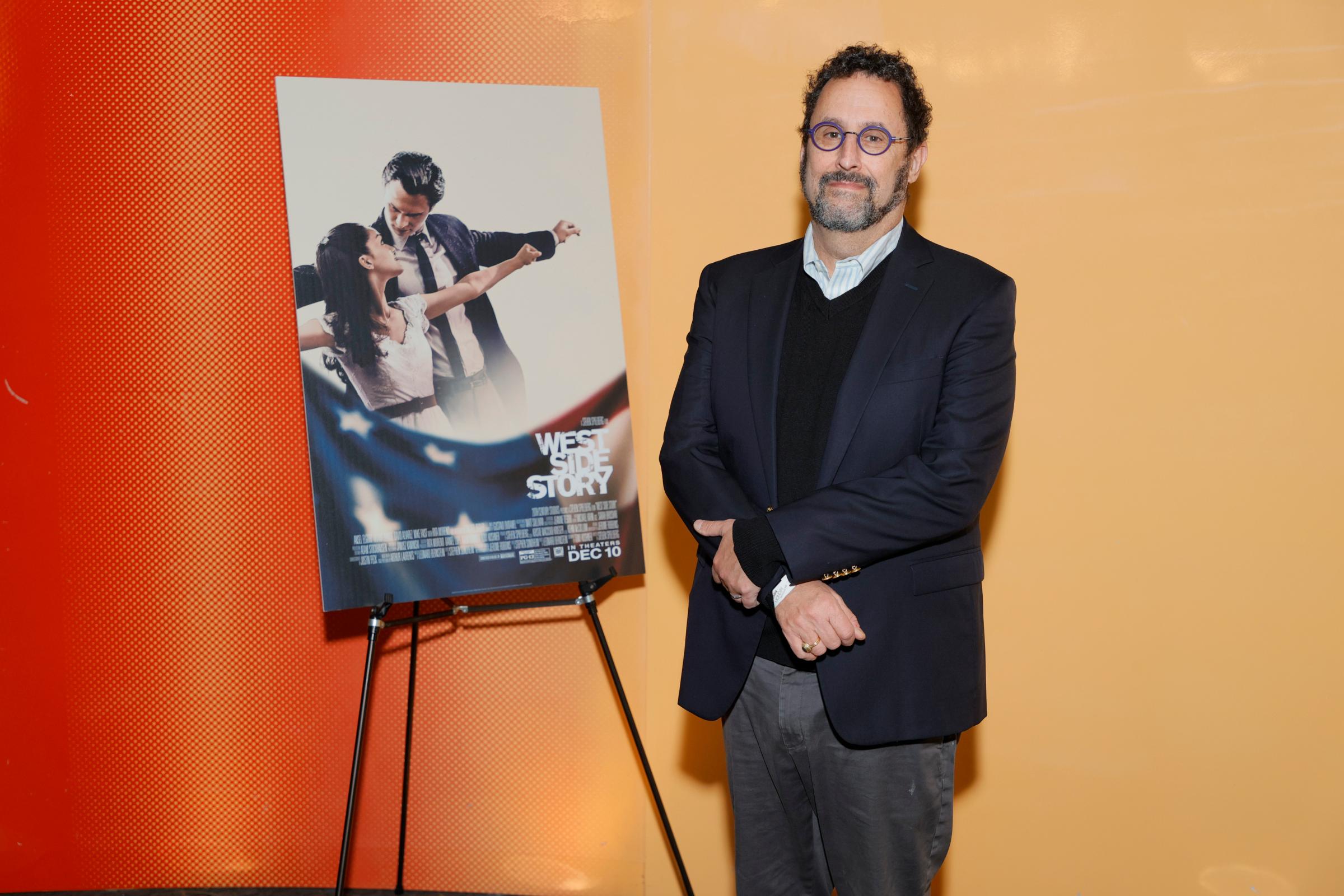

So when Kushner agreed to write the screenplay, he was faced with a perilous balancing act: to preserve the musical’s sheer brilliance while improving upon its shortcomings. So far, critics and audiences have deemed his efforts successful. The movie, which opens in theaters on Dec. 10, currently sits at a 95% Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes; in TIME, critic Stephanie Zacharek wrote: “I had no idea I needed this West Side Story until I saw it. This, possibly, is the best kind of movie, the stealth achievement that has been hiding in plain sight all along.”

Read More: Steven Spielberg’s Extraordinary West Side Story Is an Exuberant Modern Fairytale

How did Kushner pull off such a massive feat? The answer lies both in the Angels of America playwright’s individual rigor and his emphasis on collaboration. A notorious history buff—Spielberg says Kushner read 400 books on Abraham Lincoln while writing the screenplay for Lincoln—Kushner culled through countless primary and secondary documents about the history of Puerto Rico and 1950s New York. He ultimately decided to recenter the story around the ruthless real-life uprooting of low-income Puerto Rican neighborhoods by the city planner Robert Moses, who dreamed of turning the area into the luxe Lincoln Center arts complex.

With a wide-lens vision in place, Kushner then turned to several Puerto Rican cultural and historical advisors to enrich the story and ensure its accuracy and authenticity. That included his good friend Julio Monge, a dancer, choreographer and actor; the historian Virginia Sánchez Korrol, a Brooklyn College professor who has written 13 books on the subject of Latinos in the U.S.; and a braintrust of Puerto Rican dancers and actors in the cast, whom Kushner dubbed the “Puerto Rican Talmudic study group.”

Together, they feverishly workshopped and re-workshopped the script and its hyper-specific cultural details every day on set. “We kept working on this thing, because there was such an enormous feeling that—it wasn’t like, ‘Oh god, we’re going to get canceled if somebody says the wrong word’—but this deep desire to get it right and true,” Kushner said in a Zoom call earlier this week.

Kushner, Monge and Korrol discussed their approach to the musical in several group and individual conversations with TIME. Below are excerpts from those conversations.

TIME: Tony, given the heated cultural conversations surrounding this adaptation, how daunting was it for you to take on writing the screenplay?

Kushner: First, I think the conversation around works of art like West Side Story are enormously important, and that the criticism leveled at it—when it’s very specific and scrupulous—is incredibly important. I think it’s absolutely, as all art is, a product of its time. There were certain kinds of articulations unavailable to the four gay Jews that wrote the thing originally. And there are mistakes that they made, absolutely.

When they were writing “America,” for example, it’s very clear that the mistake they made was equating the relationship of Puerto Ricans in New York to the island of Puerto Rico with the relationship of Jews to the places they had come from—namely Poland and Russia, about which no Jew who emigrated from had anything good to say. They left a place of absolute horror where they were being murdered—and all they could say was, as in the song, “let it sink back in the ocean.”

What they really should have done, when they were looking for something analogous among the newer arrivals to the continental United States, was to think about the Irish and their relationship to Ireland. There was a great agony about having had to leave Ireland; a great love and attachment. But the writers didn’t do that: They made an assumption that somebody who really wanted to come here and make a life for themselves, like Anita, would have nothing good to say about Puerto Rico at all.

But I think what gets lost sometimes is how, with all of its flaws, West Side Story was a profoundly progressive—and I think profoundly honorable—attempt to do something. There was no mandate to write something on Puerto Ricans. And there’s no question there was an absolute determination to bring a group of people that had been completely excluded and unrepresented on the Broadway stage onto the Broadway stage. And they did that with rather remarkable success, including Chita Rivera, as well as Rita Moreno, who won an Oscar for playing Anita.

When you read the Spanish language press around the time of the musicals, there is criticism of it. But there’s also a great deal of excitement about somebody like Rita Moreno winning an Oscar. It was a big deal. So we didn’t approach this at all in the spirit of, “This is a terrible thing that we have to fix.” If we had thought that the musical was terrible and needed fixing, we wouldn’t have done a new version of it.

Now, many years later, it’s easier somehow to make a musical where you get into the tangle of politics in the dialogue. So Steven and I wanted to say: “What’s at the heart of this masterpiece? What was really intended?” And then expand what is too compressed, or maybe not reading, in the original. I hope it doesn’t feel like we imposed our own sort of alien ethics and ideas and politics.

Sign up for More to the Story, TIME’s weekly entertainment newsletter, to get the context you need for the pop culture you love.

The late Steven Sondheim was very involved in the process of making this movie. What did you learn from him?

Kushner: I’d known Steve since about 2001. I revered him as an artist, and over the years, we talked about if we should do something together. But I never wanted to write a book for a musical, because all the really juicy moments in a musical are in the songs. And obviously, if you’re working with Stephen Sondheim, nobody else should touch the lyrics because he was one of the greatest lyricists that ever lived.

Steve was always very critical of his own lyrics for West Side Story. It was his first professional gig, and he felt like he didn’t do as good a job as he wished. I disagreed with him in person for years about it. So I was really pleased when I called him the first time and said, “O.K., I guess I’m doing this,” and he said, “That’s great. I know you think that my lyrics are great, but they’re not perfect. And if you want me to change anything, I’ll change it.”

So I just kept calling him and saying, “Can I do this? Can I do that?” There’s one song I know of that was cut from West Side Story that I love: a song sung by Anybodys. I called him and asked if I could use it, and he said, “Absolutely—but you’ll never find a place to put it in.” And I said, “Well, just watch me.” And then about two months later, I called him and said, “You’re right, it doesn’t fit anywhere.”

About two or three drafts into the screenplay, I told him: “If you’ve got anything else that you’re thinking of, it’s getting to be time to weigh in.” I went to his brownstone on the East Side. We sat in his office for two days and went through the script, page by page. I knew that was as close I was ever going to get to work with him directly on something. And it was profoundly moving and also just endlessly fascinating, because he knew and understood the form so deeply and with such incredible clarity and force.

As is true with Spielberg or another great practitioner of an art form, he could sing both high and low. He would talk about some of the more profound issues of how you make a musical, and then also the little clever touches. He said I had made a mistake that everybody makes when you write your first book: That if there’s a pre-existing song, “You start to billboard the song before you get to it.” He said I had to find a way to flow into the song with the dialogue but not announce to the audience what the song is going to be about.

He always has said publicly how much he hates “I Feel Pretty,” because he said: “Why did I write a Puerto Rican teenager singing, ‘I feel pretty and witty and bright?’ It sounds like a goddamn Noël Coward play.”

And I called him and I said, “I’ve got an idea for the song, and it’s gonna make it work for you. I set it in Gimbels, and Maria is part of a cleaning crew. All around her are these posters that say, ‘Witty autumn wear.’ So the reason the language is slightly arch for a young Puerto Rican girl is that with her heart full of incredible joy, she’s looking at the wealth of America and saying, ‘I’m gonna have a good life and get what I want.’ So it’s sort of ironically quoting those displays.”

I said all that to him, and he said, “Well, I still hate the song. But it’s better for me now than it was.”

The lyrics to “America” are changed from the 1961 film, with the references about gun violence and overpopulation taken out. How did you approach that, and what role did Sondheim play?

Kushner: The opening is not a reworking—it’s an amalgam. We took Rosalia’s hymn to Puerto Rico from the original musical, and then added Anita’s lines from the original and the movie. There was only one line that Sondheim rewrote.

In my research, I got very interested in the question of guns and crime rates in the ‘50s. When I looked up crime statistics in Puerto Rico, I found that New York was a much more dangerous place than San Juan. So it was a cliche that everyone was shooting each other. Also, gun violence everywhere was a lot less frequent. Most of the gang killings in the ‘50s were with clubs and bricks and sometimes knives.

So when Arthur Laurents put the gun into the musical, it was a big deal, and he did it deliberately. It’s a Cold War model: He’s talking about escalation. But there was an incredibly tiny amount of gun violence in Puerto Rico—so the line about “And the bullets flying” was kind of wrong.

I said that to Steve, and he said, “Well, let me think about it.” And he called up and said, “How about, ‘And the people trying?’” He bought into the whole idea that what you’re hearing is this woman’s ambivalence. And what she’s saying is: “It’s a beautiful place, and it’s really, really hard to live there.”

After that, I wouldn’t let him change anything. He wanted to change “Free to wait tables and shine shoes,” because he said he wasn’t sure that shoeshine boys were Puerto Rican. It always bothered him. I called Virginia Sánchez Korrol and said, “Find me a picture of a Puerto Rican shoeshine guy.” So she did, and I sent it to him. And he said, “Yeah, but still, it’s not…” And I said, “You know what? ‘Free to be anything you choose/ Free to wait tables and shine shoes’ is about as great a couplet as you’ll ever find on every level, including the political. Just leave it, please.” And so he did.

A big chunk of the dialogue is in Spanish. How did you write those parts?

Kushner: I don’t speak Spanish, I’m ashamed to say. I just wanted to put placeholders in, so I wrote the lines in English and then put them into Google Translate. I thought to myself: who do I know I can turn to, to do this?

So I called Julio [Monge], who I’ve known forever, since the early ’90s. Julio is an amazing dancer, an amazing actor and an incredibly smart guy. He read the script and was horrified. He said, “I don’t know what language this is, but this is not Spanish!”

We would take each line, and slowly and fastidiously worked through the whole thing, translating every line of my butchered Google Spanish into Puerto Rican Spanish. We talked about every moment where a translation could mean this or that, or whether there was an exact equivalent.

It was more than just translation. It was also a real discussion of cultural nuance. For example, during the breakfast scene in Bernardo and Anita and Maria’s apartment, Julio said, “That’s not how Puerto Ricans made coffee.”

Monge: “I sent you a video of how you make it with the homemade cloth filter. In the scene, I was so proud of it: I was like, ‘Oh, there’s my coffee. That’s the best coffee.'”

Kushner: It was invaluable to me in terms of making corrections and making sure I got things right. Unfortunately, I had already called Steven [Spielberg] a long time before that and said, “Can I change the character of Doc to Valentina and cast Rita Moreno?” Steven couldn’t wait to call her and ask her if she’d do it. I thought he was going to wait until Julio and I had gone through the entire script and fixed the Spanish, but he didn’t. He sent her my first draft.

She called him and said, “What the f-ck is this!?” Knowing Rita, that’s exactly what she said. “This isn’t Spanish. This is appalling!” It took a couple of months to calm her down about that. And then she started getting Julio’s version of it and she calmed down.

Julio, how did you get involved in the project?

Monge: I had worked with Jerome Robbins several times, including on Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. In the last five or six years, the Jerome Robbins Foundation asked if I would be one of the people they sent out around the world to recreate his original choreography. I had been studying the hell out of it, thinking about how I did West Side Story as a young dancer many times—and I never remembered anybody caring about the background of half of the protagonists, the Sharks. Nobody talked about what happened in the ‘50s with Robert Moses, with Puerto Ricans coming in droves.

When I read Tony’s version, it blew me away. And the day we went to look at Justin Peck’s work, I remember Spielberg giving a speech about Robbins’ contribution to the piece. I’ve never heard anybody speak so clearly and eloquently about Robbins: His kinetic sense and the way he used it as a storytelling element.

And then with Tony here and the way he’s digging into the lives of these people and honoring what they lived, I knew I was part of something that respected the material. That was not trying to attack it or overdo it, but also was trying to belong to the times, to take care of honoring people’s stories, to have the right representation.

Tony, can you tell me about what you referred to as the “Puerto Rican Talmudic study group?”

Kushner: It was five singer-actor-dancers that I convened. When you do a translation into a language, there’s always going to be 50 people with 50 different opinions about what it should be. So we had in the group people who were Nuyorican and spoke Spanish; people who were still living in Puerto Rico, and so on.

We went over the script again. Then I would pass it back to Julio. It kept circulating: Virginia got involved. Julio and Victor Cruz, one of our dialect coaches, would come on set, listen in when the actors were singing, and make adjustments. They would say: “He’s hitting this wrong. It doesn’t sound Puerto Rican; It sounds Cuban.” We worked so hard on it during the shooting, and before the shooting, and for all the months Julio and I worked on it alone.

And then we got to post and there was still work to be done. There’s a quality to Puerto Rican speech and Puerto Rican life that is not evident to non-Puerto Ricans. And so Puerto Ricans had to be heavily involved.

It’s entirely and eternally Steven’s credit that there was room made in pulling together this gigantic contraption. When I came to him first and I said, “I want to put a lot of Spanish in the film and I don’t want it to be subtitled,” he said, “Great.” There was no discussion about it. He got it immediately why it was important to do it that way.

Julio, there are a couple conversations about colorism within the Latino community in the script. Can you tell me about why that aspect of Latinidad was important to include?

Monge: What’s wonderful about this version is that they opened the canvas and included a wider sense of what being a Puerto Rican is that goes beyond the stereotypical idea that they look like Europeans. That’s so not the reality, and has never been.

So I started to see opportunities. For instance, when Anita says, “Because I’m prieta, you don’t want me to be a part of the family”: We have our way to deal with race and race relations, our different tones and shades. There’s all these issues and they’re very deep and complex. But there are ways as artists that we can address them without being didactic. Where you’re just portraying a photograph of life; a moment of a person in those conditions with her skin color: How would she stand up for herself?

Virginia, how did you come on as historical consultant, and did you have any trepidation about joining the project?

Korrol: I was invited by the creative team to give a talk about my research: the history of the Puerto Rican community, and my own experiences having lived through the period that the film is set in. I was a bit skeptical and hesitant about meeting everyone. But I went because it was important that someone who has my area of expertise should attend the meeting, and that the creative team should hear from us.

By the time I left and saw a little bit of what was going on, I was very excited about it. I thought:, “We gotta give this a shot. Because if not now, then when?” Sixty years has gone by, and what a difference it makes: In the late 1960s, we established the first departments of ethnic studies, Latino studies, Chicano studies… all of these new fields of inquiry came into being. And the Center for Puerto Rican Studies was established, with archives about leaders, events. We begin to plot our history in NYC and collect information that we never had before.

The original creators, as wonderful as they were, we didn’t have that fount of information. Sixty years brings us to a point where not only are we fighting for inclusion in universities but representation in the culture. This is a battle that is still going on in many forms. That makes the 2021 film so much more relevant than it ever was.

I also want to ask about the very powerful moment when the Sharks sing the Puerto Rican anthem, “La Borinqueña.” How did that come about?

Monge: We discussed the political and social and cultural landscape of around 1957. I was bringing to the table the fact that there was a law in Puerto Rico called the Gag Law, or La Ley de la Mordaza, which started in 1948. It prohibited Puerto Ricans on the island to raise a Puerto Rican flag, sing the Puerto Rican anthem, assemble and get together for political reasons criticizing the United States. For nine years, we had that—and they could take you to jail for 10 years or would fine you $10,000.

It was politically-charged times. 1958 was the first year they had the Puerto Rican Day Parade. The Puerto Ricans in New York, Philadelphia, and the other main cities they migrated to were very politically involved with all the developments on the island. This goes back to the 1800s: the political fights against Spain and colonization; Eugenio María de Hostos meeting with Jose Marti, forming a chapter of the group fighting for the independence of Cuba.

So this movie is a little moment right there in the middle of those changes toward establishing us as a respected community. And that’s what I think is fascinating about the way Tony approached it. In his prologue, it’s not two gangs fighting: you see the damage on the Anglo-Saxon side, and they’re vandalizing the Puerto Rican side of the neighborhood. And so you see these working class kids having to come out to defend it and take justice in their own hands because of the ineptitude of the system.

Korrol: When I first read that in the script, I thought it was bold, but I liked the idea, because it fit historically. There were two sets of lyrics for “La Borinqueña”: one written in support of the Puerto Rican revolution in 1868, and another after the revolution was suppressed. Even the revolutionary flag that was flown, which had a light blue coloring, was banned.

In 1952, Puerto Rico became a commonwealth of the U.S., and they raised a Puerto Rican flag with a dark blue coloring to it, similar to the blue on the American flag. Puerto Rican Nationalists and others were very vocal about opposing the new flag; it became a cause célèbre. And then in 1954, the Nationalists promoted an assault on the U.S. Congress.

So these movements are happening at a time when in this story, a group of Puerto Rican guys were banding together to try to save their turf, and are very impressionable. And who would they choose to emulate, conservatives or Nationalists? And so Bernardo’s singing of “La Borinqueña”—with the original revolutionary words—makes perfect sense. And Tony understood this history and weaved it all into Bernardo’s backstory.

Tony, one of the songs that felt most invigorated by this adaption was “Cool,” which gets a completely new narrative context. How did you go about reimagining that song?

Kushner: “Cool” is one of the most exciting dance numbers ever choreographed; I think most people would probably agree that it’s the most influential dance number in the film. But it always seemed odd to me that if you listen to the words, it’s all about lowering the emotional temperature and taking it easy. When you’re approaching the end of your drama, that’s an odd thing to want to do. So I thought, there’s got to be something in here where the narrative can flow through it.

I also had been thinking a lot about the Jets’ relationship to older gangs like the Hudson Dusters, a really serious Irish gang. I decided that Riff’s father was probably a gangster connected to the Hudson Dusters. That the mafia had kind of pushed them out, but there were still remnants around. And the Jets would be a kind of teenage auxiliary to a really serious gang of career criminals.

In this origin, Riff has taken over the Jets, but he’s not a natural born leader. He realizes he has to lead his gang into a rumble and he’s scared. So he wants a gun because that will give him more authority. I decided that “Cool” would work as a game of keep-away once they’ve got it. None of them have ever had a gun or necessarily even seen one except with the police. So they’re really excited about it, and then sort of tossing it around and playing cowboys.

I’ve always been interested in parkour: There’s films on YouTube where kids are jumping over buildings and bouncing off the walls. It’s just a very interesting sort of urban form of dance. And Justin Peck grabbed the idea and ran away with it, and came up with something extraordinary.

There’s one moment in the movie where one of them lands really hard on the pier, and this giant cloud of dust explodes. That’s a gimmick that Steven came up with when he was a teenager. He was like 13 and making a war movie, and he invented these little catapults, where one end of a stick is beneath the surface of the ground where there’s a lot of dust. If one person jumps on the raised part of the stick, the dust flies up. In our next World War II movie, The Fablemans, he did it to simulate bullets hitting the ground. And when we were talking about “Cool,” he said, “Why don’t we do my old trick with the catapult?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com