A version of this article was published in TIME’s newsletter Into the Metaverse. Subscribe for a weekly guide to the future of the Internet.

It’s hard to go online these days without seeing someone yelling about the metaverse, whether in rapture or derision. Depending on whom you ask, it’s the inevitable future of the Internet or a billionaire’s flight of fancy; a gaming utopia, an “infinite office,” a brand strategy, an NFT playground, a sci-fi illusion. Virtually every news outlet—including this one—has published articles attempting to make sense of it all. The noise around the term “metaverse” is now loud and constant enough to render it almost meaningless.

So what, exactly, is the metaverse? Why did Mark Zuckerberg make it his new life’s work, and why are other tech companies pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into their own competing visions? What role will cryptocurrencies and the blockchain play in this future? And most importantly, how is any of this going to impact your life?

I’m going to try to unpack all of that and more in a new weekly newsletter, Into the Metaverse. I come to you with a background in reporting on the intersection of culture and business, and I admit I still have a lot to learn—having descended only two or three rungs down the rabbit hole. Over the past year, however, as I’ve dived into the curious phenomenon of NFTs, I’ve talked to many people—from Metakovan to Trevor McFedries to Steve Aoki—who are devoting their lives to building the metaverse block by block. I’m hoping this newsletter will spotlight the work of others at the forefront of the metaverse: to show how their efforts are already bringing about significant change, and how a new kind of arms race has emerged that will define how we engage with the Internet and each other in the decades to come.

This first newsletter will be a brief introduction and explainer (maybe the first, or 15th you’ve read on the topic) on the metaverse. (On a related note: If you’re working on something interesting, or have any comments or concerns, please drop me a line at metaverse@time.com.)

What is the metaverse?

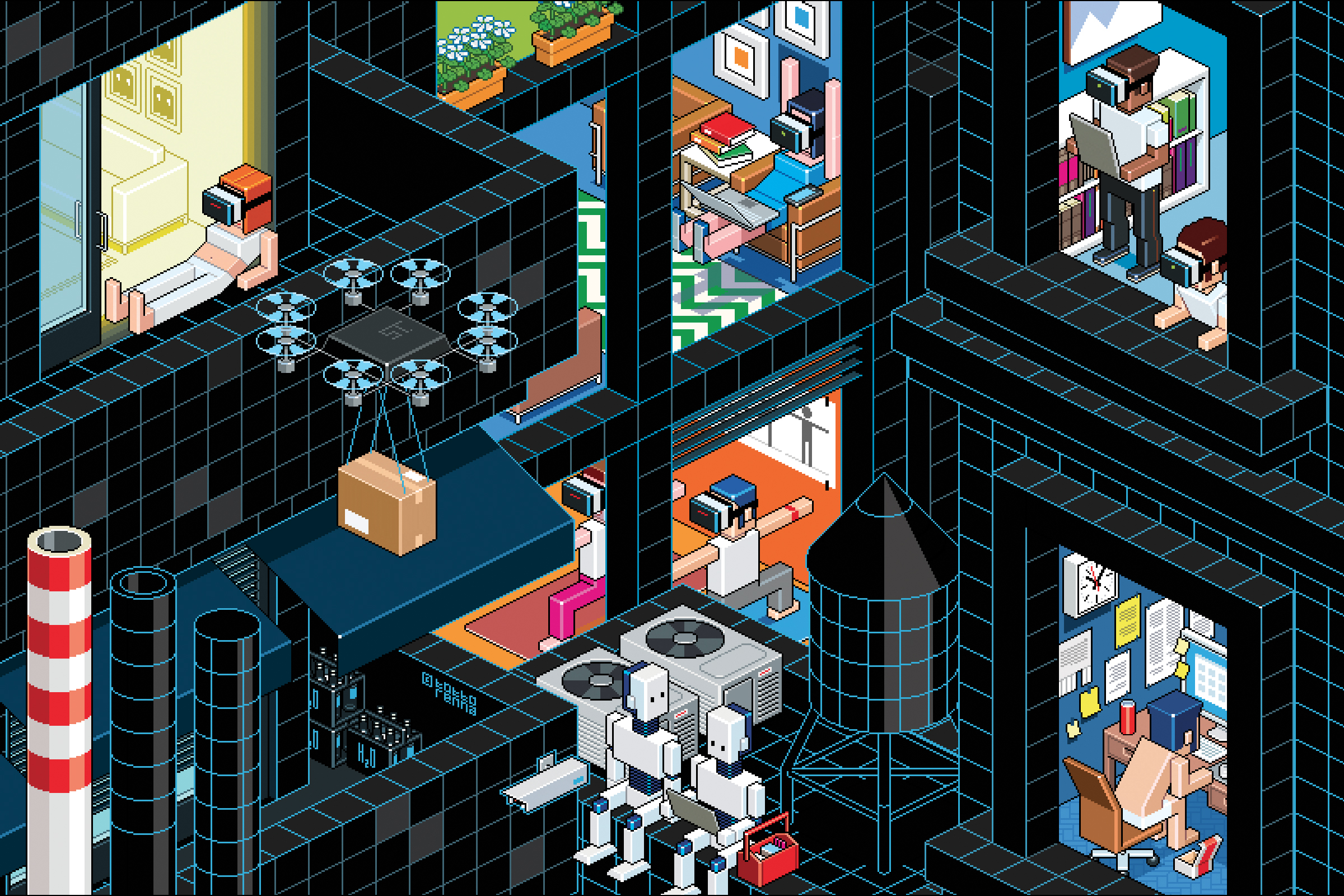

For some people, the metaverse has a strict definition: it’s an advanced version of the Internet that you are inside of—instead of merely looking at. In this singular 3D world, you walk around as an avatar, interacting with other avatars; you can buy and sell virtual stuff, go to work, form communities, play games, wage war.

Two sci-fi novels were central toward this conception of the metaverse: Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, which actually coined the term, and Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One. In both novels, the metaverse was entwined with dystopia: it held sway in a society that was in ruins and controlled by shadowy corporations. For the characters in both books, the metaverse offered the allure of escape from their bleak existences while also reinforcing corrupt power structures.

This singular version of the metaverse is decades away from fruition, if even possible at all. Both VR (virtual reality, which typically uses a headset) and AR (augmented reality, which layers the virtual world on top of the real world) have yet to penetrate fully widespread adoption. The amount of social coordination, infrastructure building and technological advancement it would take to build a universal metaverse like those portrayed in sci-fi is immense. And crucially, it’s unclear if this is something that people actually want.

It’s also true, however, that over the past year and half, much of human life has moved online in unprecedented ways. As the pandemic upended our real-world work and social spaces, the average American spent 7 hours a day online last year, according to one study. We went to birthday parties on Zoom and sent the host presents via Amazon or Cash App; we attended company quarterly meetings over Microsoft Teams while sniping about the CFO with our colleagues on Slack. We spent billions of collective hours and hundreds of millions of real dollars in games like Fortnite, Roblox and Animal Crossing. In April 2020, we might have been among the 27 million unique visitors who watched Travis Scott give a virtual concert in Fortnite—that’s 67 times the number of people who went to Woodstock in 1969.

So in a looser sense, the metaverse is already here—in bits and pieces. I’d like to define the metaverse, for the purposes of this newsletter, as the ways in which our physical and digital selves are becoming increasingly blurred. Many people see the metaverse not as one unified world, but a scenario in which we will be able to seamlessly bring ourselves and our stuff—from fashion to art to spending money—with us from platform to platform. The ideas of digital sovereignty and interoperability are key: Instead of having separate Facebook and Twitter accounts in which everything you post is owned by those corporations, you will be able to own your digital personhood and all of your ideas and digital belongings wherever you go.

Why you should care

The past year and a half has exposed both extreme benefits and drawbacks of our unprecedented global connectedness. On the plus side, many people were able to continue earning a living without having to go into an office, giving them freedom of movement and location outside dense urban centers. People found solace and escape in online communities and new streams of revenue selling products or art online. Organizations and social justice movements connected people and ideals across the world.

On the flip side, the pandemic led to one of the greatest wealth transfers in history— specifically into the pockets of Big Tech. It also accelerated many of the worst trends in the digital world. Misinformation and hate speech spread like wildfire under the purview of social media companies whose primary duty was to their shareholders’ wallets. Our data was farmed out from us, creating an age, as tech pioneer Jaron Lanier says, of not simply targeted advertising but “behavior modification.” Algorithms derailed the self-esteem of younger users, especially those belonging to Generation Z. And many of us developed Zoom fatigue, showing the limits of the abilities of even the most cutting-edge technology to connect us the way it does in real life.

Nearly all of these effects, both positive and negative, were borne out of decisions made by a few guys in Silicon Valley over the past two decades. Ideas that might have seemed silly before they existed—virtual assistants, photo-based social apps, video filters— are shaping the way we engage with the world and each other.

Now, a battle is being waged over what the next stage of the Internet will look like, and who will control it. You may find many of these efforts and developments—from governance tokens to volumetric video to haptic gloves—irrelevant or indecipherable, especially in the face of much greater global problems. But they are already having huge impacts on their practitioners and generating astonishing streams of income for a diverse set of people across the world. As users continue to adopt these newfound technologies, their ability to transform society in unpredictable ways will only accelerate.

“I think this transition is like the one from desktop to mobile,” Annie Zhang, who hosts the podcast “Hello, Metaverse,” says. “Mobile Internet was not completely groundbreaking—but the way in which people interacted with the world fundamentally changed.”

Who is building the metaverse?

Some of the players building the metaverse are in it for the money and power; others are more interested in resolving the huge problems endemic to our current online structures. Many more fall somewhere in between these two aims.

The first camp of contenders includes the powers that rule our current online existence, including Facebook, Microsoft and Google. These companies have profited immensely from cornering their respective markets—and they obviously want to be a part of whatever comes next. (As Black crypto policy expert Cleve Mesidor told my colleague Janell Ross last month: “The Internet was supposed to be decentralized, and today it’s owned by four white men.”)

Microsoft, Tencent, Snap, Nvidia and others have started pouring resources into developing the metaverse—but the company leading the charge most publicly is Facebook. In October, Mark Zuckerberg changed the name of Facebook’s parent company to Meta and proclaimed of the metaverse, “You’re going to be able to do almost anything you can imagine.” Facebook will soon hire 10,000 workers in the EU to build out Zuckerberg’s vision. The company already owns Oculus, a VR goggles company, and is trying to coax people to buy cheap headsets as a gateway to the metaverse.

The second camp of contenders includes the gaming companies that have already created their own thriving virtual worlds, like Epic (the maker of Fortnite), Roblox, and Unity (whose online engine powers Pokémon Go and League of Legends). Video games are the closest things we have to singular metaverses right now: social worlds in which virtual currency has actual value, creators can be compensated for their labor and commerce and art thrive without needing anchors in the real world. These companies have a crucial advantage in their already-thriving user bases, who are disproportionately young, tech-savvy and understand the value of digital goods.

The last group is perhaps the most intriguing: the proponents of an idea known as “Web 3,” who envision a world in which every action or interaction we undertake online will no longer be under the purview of megacorporations. They dream of an “open metaverse” in which online spaces are owned collectively; in which every person owns their data and can reap the profit of their online creations without corporate middlemen taking a slice. Crucially, they believe blockchain technology—a tamper-resistant digital public ledger—is the bedrock on which all of this will rest. Blockchain-based worlds like Decentraland, Somnium and Sandbox are already building out their communities under this vision, although they count their daily active users in the thousands as opposed to the tens of millions of Fortnite and Roblox.

Many of the leaders in the Web 3 space see themselves as diametrically opposed to the first camp of corporate forces—and locked in an ideological and technological battle that will play out over the next decade. “If we’re going to exist in some kind of a hybrid virtual physical world, I think we’re in a far better situation if people are educated about the importance of ownership, censorship dynamics and even the ability for users to opt out of certain environments,” says the technologist and artist Mat Dryhurst, who co-hosts the podcast Interdependence. “I don’t want the next virtual world to be determined by decisions made in Palo Alto. There ought to be an open, permissionless environment where a large group of different people internationally have some say in the way in which that is governed.”

But there is plenty of overlap between the three groups. Many of the biggest players have expressed an interest in building an “open” metaverse, but in the past they’ve proven themselves resistant to integrating their systems or sharing data. (Anyone trying to text a group that includes both iPhone and Android users knows this all too well.) Tim Sweeney, the CEO of Epic Games, has verbally aligned himself with the third camp, even as Fortnite gains more and more market share in this new era: “As we build up these platforms toward the metaverse, if these platforms are locked down and controlled by these proprietary companies, they are going to have far more power over our lives, our private data, and our private interactions with other people than any other platform in previous history,” he said in May 2017.

And not all Web 3 folks are all in it for the kumbaya idealism. There are plenty of speculators in the space, for which the development of blockchain-based infrastructure serves to boost their cryptocurrency investments. (Crypto-investing is far from a niche activity anymore, however: a study from this summer showed that 13% of Americans traded crypto over the previous year.) While crypto enthusiasts are fighting against flawed structures, they have also experienced plenty of hiccups along the way. Studies have shown that NFT earnings are pooling into the hands of a few wealthy collectors, while major crypto companies like Tether, Binance, and OpenSea have suffered from legal disputes, hacks and insider trading in the last year.

So what will this newsletter be about, exactly?

As I mentioned earlier, this newsletter will chart the many ways that our physical and digital selves are becoming more and more entwined. In some weeks, I will track the progress that some of the above companies are making toward fulfilling their visions. Other weeks, I will focus more on how technological tools are impacting our current world. How is crypto impacting the countries that have adopted it early on, including El Salvador, for instance? Who are the gamers in the Philippines making huge money off gaming in Axie Infinity, and how are their efforts impacting their country?

Loosely, the topics will fall into five overlapping categories that intersect in the fields of business and innovation: culture, work, economics, gaming and regulation. How is gaming becoming work? What does the development of smart contracts—agreements written on the blockchain—mean for businesses? Could the concept of decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) make us rethink how corporations are run? And what are the ways in which decentralization opens up its own bag of new problems?

There’s a lot to bite off here; we’re going to take it one week at a time. The newsletter will also include a roundup of some of the metaverse news of the week. See you there.

Subscribe to Into the Metaverse for a weekly guide to the future of the Internet.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com