The Harder They Fall, a film arriving on Netflix on Nov. 3, starts with a message plainly stating that its “events are fictional.” Over 137 sprawling minutes, director and co-screenplay writer Jeymes Samuel weaves an epic and blood-splattered tale of revenge in the Wild West, tracing an outlaw as he hunts down the man who killed his parents.

But while the story is fake, many of the characters in the film share their names with real life historical figures: Nat Love, Bass Reeves, Rufus Buck, Cherokee Bill. Samuel’s characters share some resemblances with their namesakes while diverging drastically in other ways; most have no actual connection to each other. In making The Harder They Fall, Samuel hopes to call attention to how Black pioneers shaped the culture and history of the American West but have since been cut out of its legacy. “We have been ignored from the history of the Old West and the cinematic presentation of what the Old West was,” Samuel told the New York Times earlier this month.

The Harder They Fall continues a current wave of Black storytellers mining this historical material for their work, joining titles like Watchmen, Hell on the Border and the upcoming Outlaw Posse, Mario Van Peebles‘s follow-up to his 1993 western, Posse. “Most people don’t know that history: They don’t know Isom Dart or Deadwood Dick or Stagecoach Mary. White male supremacy has reigned supreme in Westerns,” Van Peebles told TIME earlier this year. Two of those names appear in The Harder They Fall. Below is a primer on them and the rest of the true stories behind the film.

Nat Love

Riding at the center of The Harder They Fall is the outlaw Nat Love, played with a smoldering intensity by Jonathan Majors. Majors’ Love engages in petty thievery and seeks revenge on a man who killed his parents and then branded him when he was a child.

Much of what we know about the real Nat Love comes from his 1907 autobiography: The Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as “Deadwood Dick.” But it’s disputed how much of Love’s book is fact as opposed to self-mythology. The history professor Michael N. Searles contends in the book Black Cowboys in the American West that “few sources corroborate his story.”

In his autobiography, Love writes that he was born a slave in 1854 in Tennessee, where he learned to break horses on his owner’s plantation. After the Homestead Act—which allowed former slaves to claim land in an expanding America—Love rode west and became a ranch hand in Kansas. Over the coming years, Love says he roved around the west, herding steers and winning contests in roping bridling, saddling and shooting, earning the moniker “Deadwood Dick” for his prowess (This nickname was claimed by at least five other people, however). Love shares stories of riding up to 100 miles a day, fighting Mexicans and Native Americans—who he demeans often and refers to as “blood thirsty red skins”—and befriending other cowboy icons like Buffalo Bill and Billy the Kid. “There was no law respected in this wild country,” Love writes, “except the law of might and the persuasive qualities of the 45 Colt Pistol.”

Whether or not his particular tales are true, it’s indisputable that countless Black cowboys went on similar adventures during this period. As Texas was developed into a cattle capital in the early 19th century, slaves played an integral role in managing livestock, accounting for a quarter of the region’s settler population in 1825. After the Civil War, many former slaves became paid cowhands and cowboys, shepherding herds for hundreds of miles in between trading centers like Denver and Kansas City. Overall, one in four cowboys at the peak of westward expansion was Black.

By the time that Love had written his autobiography, his alleged exploits were long in the rearview. In 1889, he got married and later became a Pullman porter, one of the few jobs available to Black men at the time.

Bass Reeves

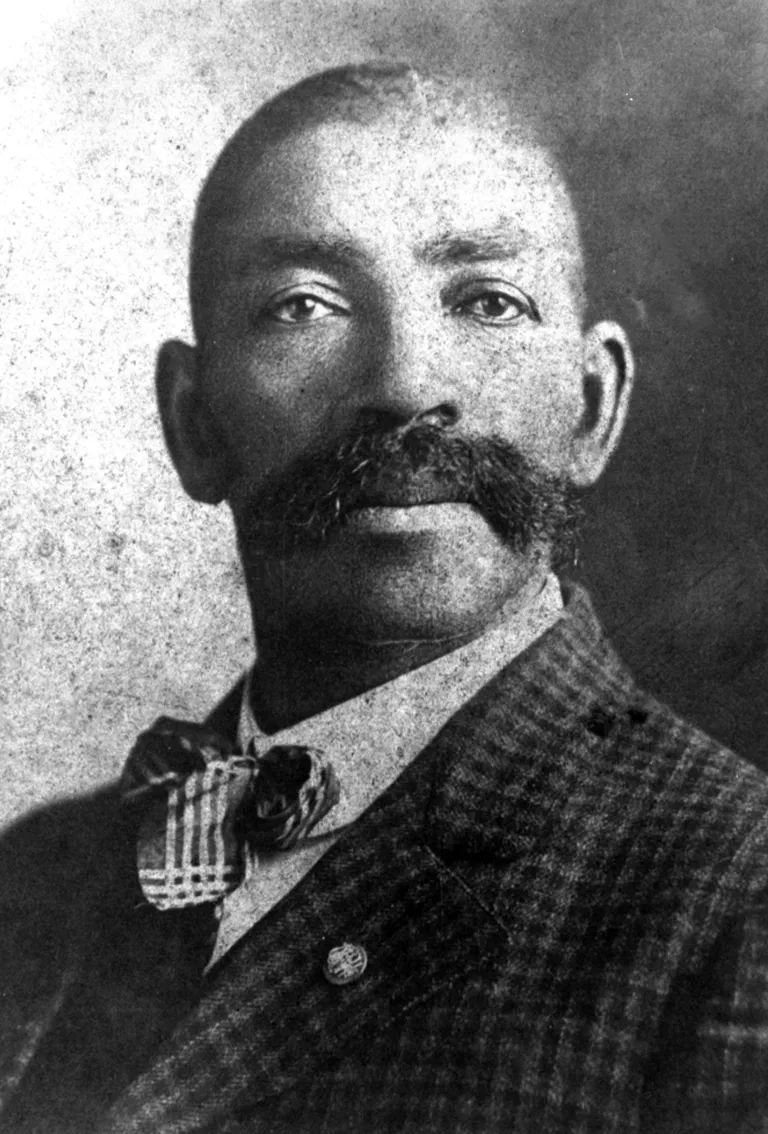

In The Harder They Fall, Majors’ Nat Love finds an unlikely ally in the U.S. deputy marshal Bass Reeves (Delroy Lindo), who helps him hunt down Rufus Buck. Reeves was a revered lawman in Indian Territory for three decades starting in 1875, handcuffing more than 3,000 felons; he was known for being unbuyable at a time in which many lawmen accepted bribes or were part of criminal enterprises themselves.

Reeves was born a slave and escaped to Indian Territory as a young man. Some accounts say he fled after killing his enslaver in a dispute, and proceeded to live among the Cherokee, Creeks and Seminoles until emancipation made him a free man. In 1875, Reeves signed up to be a marshal when Judge Isaac Parker recruited hundreds of new officers to attempt to bring law to a territory full of violence and subterfuge.

Reeves was an exemplary lawman for several reasons: he spoke several languages, was a diligent detective and an honest shooter—in multiple senses of the word. Legend has it that he was barred from turkey shoots at picnics and fairs because he would win too easily. One sharpshooter said Reeves “could shoot the left hind leg off a contented fly sitting on a mule’s ear at a hundred yards and never ruffle a hair.”

He had a legendary walrus mustache and equally legendary disguises, sometimes posing as a cowboy or a con man to win the trust of his targets. He was a devout churchgoer and famously principled: He even arrested his own son Benjamin, who had been charged with killing his wife.

Reeves was the longest serving deputy U.S. Marshal in Indian Territory, holding his post for 32 years. Some believe that Reeves was the basis for the Lone Ranger. Two years ago, he showed up as a character on Watchmen. He will also be the subject of a new TV series from Morgan Freeman’s production company.

Rufus Buck

Idris Elba’s Rufus Buck walks a path not unsimilar to one of his most famous characters: The Wire’s Stringer Bell. Like Bell, Buck is a lifelong criminal hardened by systemic injustice and racism. He believes that through his criminal enterprise, he can build legitimate business structures that will better his community—but takes ruthless approaches to get there.

In real life, Rufus Buck didn’t make it past 18. Buck was born in the late 1870s, the son of a Black mother and Creek Indian father. In the 1890s, Buck created a gang with other Black and Creek Indian teens and proceeded to rampage through Arkansas and Oklahoma, robbing stores, killing a U.S. deputy marshal and allegedly violently beating and raping their victims.

Historians say that Buck’s terrorizing was not without purpose: he strove to incite a Native American uprising that would wrest Arkansas and Oklahoma back from the white settlers who were encroaching upon Indian Territory in overwhelming numbers. “His dream was impossible; and he used the same violence to achieve it that he saw all around him,” wrote the novelist Leonce Gaiter, who turned Buck’s tale into the 2011 novel I Dreamt I Was in Heaven: The Rampage of the Rufus Buck Gang.

In 1896, U.S. Deputy Marshals and police tracked down the gang outside of Okmulgee, engaging in a day-long gunfight that ended with the gang’s surrender. (There are no records indicating that Bass Reeves was part of this hunt.) Unluckily for Buck’s gang, their cases fell under the purview of the previously-mentioned Judge Parker, who was known as the “Hanging Judge” for his ruthless sentencing, and unsurprisingly sentenced them to death at Fort Smith. While many men had been hanged there for murder over the previous decades, gang members Maoma July and Sam Sampson were the first ones to be hanged for rape. The Supreme Court upheld the verdict, and the quintet was executed all on the same day.

Cherokee Bill

While Cherokee Bill, portrayed in the film by Lakeith Stanfield, did not run in Rufus Buck’s gang as The Harder They Fall depicts, he was a feared criminal in his own right. He was born Crawford Goldsby; his mixed heritage included Sioux, Mexican, Black and white ancestors. As a teenager, he rode with the Cook Gang, stealing horses, holding up trains and banks and killing anyone in his way. He even shot and killed his brother-in-law after a dispute.

While robbing a store in 1894, Cherokee Bill shot and killed a spectator in cold blood, precipitating a manhunt. He was eventually reeled in by Deputy Marshal W.C. Smith, another Black man, and sentenced to hang by Judge Parker, who described him as a “bloodthirsty mad dog who killed for the love of killing” and as “the most vicious” outlaw in Oklahoma, according to journalist Al Cimino’s Gunfighters: A Chronicle of Dangerous Men & Violent Death. Cherokee Bill staged an unsuccessful jailbreak before being killed. Like Buck, he did not live to see 20.

Stagecoach Mary

Zazie Beets’ Mary Fields is Nat Love’s romantic foil; she owns a saloon and is also something of a burlesque performer. The real life Mary Fields became renowned in middle age, when she agreed to leave her home in Ohio to join a Catholic mission in the wilds of Montana.

Mary Fields is said to have been born on a Tennessee plantation around 1832. For many years, she served a family in Cleveland, Ohio. After being emancipated, she got a job as a groundskeeper at a Toledo convent, and then followed her friend who was an Ursuline mother superior deep into Montana Territory. That woman, Mother Amadeus, had grand visions for her Catholic outposts, and especially for young Native American women she hoped to convert. But her health deteriorated, especially in an unforgiving Rocky Mountain climate in which both snowstorms and floods were common.

So when Mother Amadeus asked for Fields’ help to carry out her visions, Fields boarded a train west and proceeded to take care of nearly all the logistics of survival for the mission’s nuns and boarders. She maintained a vegetable garden and henhouse; drove buggies and wagons through rough terrain on horseback, hauling lumber, stone, tools, medicine and food; washed laundry and even hunted wild game. “She did everything that we couldn’t,” read a nun’s entry from the Saint Peter’s Ursuline Annals. Records from 1885 state that she earned $50 a month for her troubles.

Fields was also reputed to have a temper, and to engage in prototypically masculine activities like drinking, smoking, handling guns and even wearing men’s clothing. When a rumor circulated that Fields had participated in a gun duel, the local bishop kicked her out of the convent. She moved to Cascade, became its lone Black resident, and worked as a laundress.

In the 1890s, Fields answered the call for U.S. postal drivers, becoming one of the first known African American woman star route mail carriers in the United States. During this time, lore of her ruggedness and independence grew; stories say that she shot at bandits trying to rob her cart; that she was six feet tall and over 200 pounds, “a match for any two men in the Montana Territory” with “the temperament of a grizzly bear.” Miantae Metcalf McConnell, in her essay “Mary Fields’ Road to Freedom,” wrote: “In winter, when horse or wagon passage proved impossible, she threw the U.S. mail sack over her shoulder and huffed the thirty-four-mile roundtrip on snowshoe … Nothing deterred her sense of duty.”

But those stories didn’t gain Fields legal or communal respect. In Cascade, she frequently babysat for local families but was never integrated into social settings. She became the mascot of a local baseball team and was treated more as a character than a person. In 1889, a gendered law was passed that prevented her from entering saloons, where she loved to hang out, or carrying around her signature handgun. She died in 1914.

Jim Beckwourth

RJ Cyler plays the cocky Jim Beckwourth, who believes himself to be the quickest draw in the west. The real Beckwourth actually had a far more rip-roaring life. Beckwourth was a mountaineer and explorer who went on fur-trapping expeditions across the Rocky Mountains. In the 1820s, he left white society to live among the Crow people, fathering several children there. He returned to life to the states and participated in several wars on the side of the U.S., according to Britannica. Near the peak of the Gold Rush, Beckwourth “discovered” a pass through the Sierra Nevada, which would soon be known as Beckwourth Pass and help usher in a population boom in Central California.

He told his life story, with plenty of embellishments, to the journalist Thomas D. Bonner, whose 1856 book, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, Pioneer and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians, made Beckwourth a person of public interest at the time.

Bill Pickett

The real Bill Pickett wasn’t a sharpshooter, like Edi Gathegi’s character, but perhaps the most famous Black rodeo rider of the early 20th century. Bickett grew up in Oklahoma in a ranching family and soon pioneered the rodeo sport of “bulldogging,” in which he would grab a bull by the horns and bite into its upper lip to immobilize it.

Pickett soon adopted the moniker of the “Dusky Demon,” and performed in fairs and exhibitions all over the world—including for presidents and the British royal family. With the onset of silent films in the 1920s, Pickett appeared in two movies: a rodeo documentary called The Bull-Dogger and an outlaw flick called The Crimson Skull. In 1971, Pickett became the first Black cowboy inducted into the Hall of Fame of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com