Issa Rae’s Insecure has told many stories previously unseen on mainstream television. Over 34 episodes, the show has covered the mundane aspects of Black female friendship; the complexities of colorism and Afrolatinidad; the intersection between Black masculinity and mental health; even the power dynamics of oral sex.

But for Rae, setting precedents behind the camera has been just as important as what happened in front of it. Several recent studies have shown that Black creatives are underrepresented in nearly every aspect of filmmaking, while interview after interview has revealed how they are often ignored in writers rooms, sidelined into “diversity” slots without upward mobility and shut out of top decision-making positions. The result has led to both a huge undervaluing of Black-led projects, as well as onscreen representations of Blackness that, for many Black people, felt foreign to their actual lives.

When Insecure was greenlit on HBO in 2016, Rae, a newly minted showrunner, hoped to build Insecure not only into a formidable show but also a pipeline for Black writers, directors, editors and other creatives to gain experience and credibility in a cutthroat industry resistant to change. “That was a super conscious effort: It was like ‘Oh, the door is open to everybody—come on in,’” Rae tells TIME. “If we only get one season, at least you can say you have this experience and get on to the next show.”

Insecure, of course, outlived its first season: it was a runaway hit for HBO, dominating social media conversations every Sunday night. As the show wraps up with its fifth season, premiering Oct. 24, the impacts of Rae’s emphasis on growth and mentoring are already being felt, as a veritable constellation of power players who cut their teeth on Insecure are fanning out across the Hollywood landscape. Just as shows like The Simpsons and Freaks and Geeks served as essential breeding grounds for talent, it’s likely that the reverberations of the Insecure incubator will be felt for years to come.

“It was its own kind of school experience—on inclusion, on giving opportunities, on developing authentic stories, on fighting for untraditional locations,” says Deniese Davis, who started out as an assistant on the show’s pilot and now runs her own production company. “I can’t foresee any of us not wanting to replicate some small part of what made Insecure so special.”

Learning on the Job

In the beginning, Insecure was led largely by first-timers: Rae, a first-time TV show creator; Prentice Penny, a first-time showrunner; Melina Matsoukas, directing her first episode of narrative TV; Amy Aniobi, a first-time TV producer. “It was scary, and obviously you have moments of imposter syndrome,” says Aniobi. “But at the end of the day, how else do you learn but on the job? We had the safety to fail: We all had each other’s backs because we were learning together.”

Given this mentality, Rae and the rest of the creative team tried to fill out their staff not based on experience—which they found was often a part of the gatekeeping that kept doors closed to young voices of color—but based on hunger, talent and fit. Rae says that this approach was sometimes met with pushback by HBO. “I’d hear, ‘This director doesn’t have much experience. Are you sure?’ It’s up to me to be like, ‘Yes I’m sure. I’m willing to put my name behind the fact that I’m sure.’”

Deniese Davis is an example of someone who never would have been brought on board under entrenched Hollywood hiring practices. She had been hustling for years for low-budget online video projects—including with Rae on the web series The MisAdventures of Awkward Black Girl—but had never previously worked in the television space. When hiring began for the Insecure pilot on HBO in 2016, she was told by a producer that she didn’t have enough experience to join: that “the way TV pilots work, I just can’t bring in an outside nonwriting producer, because we don’t know there’s a series yet,” Davis remembers hearing.

Instead, Davis accepted the position of assistant, but still did the work of a producer anyway. “Melina, Prentice and Issa never regarded me as an assistant. They all said, ‘Deniese is a producer, and allowed me to help however I could,” she says. After the series was picked up, Davis was promoted to an official producer. “Issa opened the door for me. I don’t know how else I would have made that jump from the indie low-budget world to TV,” she says.

In a recent interview with Produced By Magazine, Penny says that Insecure filled out its ranks by asking agents and managers around town to send them young creators of color. They also held a contest in which young people could send in edited rap videos as submissions to become PAs. “It’s not intuitive—but it showed they had initiative to write a rap, talk about their skills, shoot a video, edit it together,” Aniobi says. “All those things showed us: ‘You’re not just a PA, you’re creative yourself.’” One of the contest winners, Kindsey Young, announced on her first day on set that she wanted to join the writer’s room one day. Two years later, she would be sitting among them.

You Know What That Is? Growth

Getting new faces in the door was the first step. The next stage would be to build a culture of growth (as Natasha Rothwell’s character Kelli expressed in a widely-shared GIF). Syreeta Singleton, who started as Penny’s assistant and a writer’s room PA, says that people were consistently teaching their jobs to those one level down, “because the thought was that we’re all going to move up.”

While Singleton had been sharpening her writing skills long before working on Insecure, she came to the show from a period of odd jobs from babysitting to working in PR, and barely knew what a writers room was before her first day. But Penny took her to high-level meetings and constantly encouraged her and other assistants to pitch and write ideas.

“Prentice and Issa were both adamant about making sure people grew on this show: they know we’re all there because we want to write,” Singleton says. She moved up from assistant to script coordinator to story editor—and even wrote one of the series’ most climactic episodes, 2020’s “Lowkey Movin On,’” in which Issa finally throws a block party in Inglewood.

When Insecure was between seasons, Singleton says that Rae and Penny would also advocate for her to be hired on other shows. Through her newfound connections, she soon landed jobs writing on Black Monday and Central Park, deepening her bona fides in the industry.

“I’ve watched [Singleton] grow from season to season, as one of the people I would be the most excited to get scenes from, to watching her pen her own episode,” Rae says. “To see her grow in confidence has been really stellar to witness.”

The emphasis on mentoring didn’t help just the mentees, but also the show overall. Rae says that at the show’s beginning, she received plenty of pressure to cater the show to the white gaze; to elevate the role of Issa’s white colleague Frieda (Lisa Joyce), for instance. This sort of framing is far from new: A recent Atlantic article described the history of the “negotiated authenticity” of Black television, in which Black screenwriters have been tasked for years to create a version of Black life that is acceptable to white showrunners, studio executives and viewers.

By nurturing writers inside their walls, Insecure was able to develop a pool of young talent who had practiced writing in the show’s voice, and could step right into full-time writing roles with authenticity and humor when more veteran staff writers moved on to other projects. “Even when the room had turnover, we weren’t playing catch-up: having that pipeline meant that we were getting new voices in the room who already understood the show,” Aniobi says.

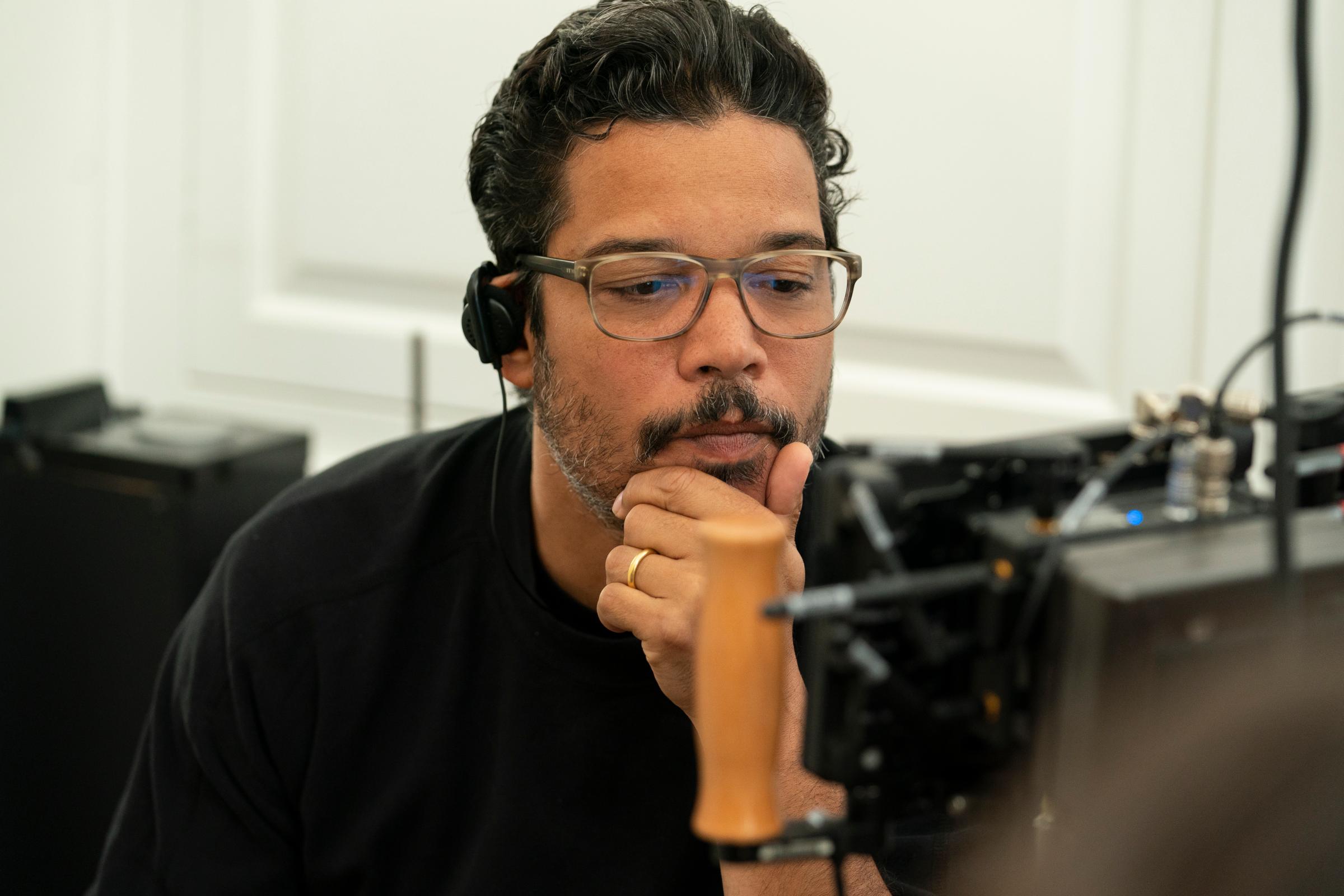

Directors Get Their Shot

Rae also made it a priority to hire directors at varying career stages, giving them opportunities to expand the industry’s narrow conception of them. One of those was Kevin Bray, a veteran director who had spent the early 2010s working on middlebrow dramas like Franklin & Bash and White Collar. “She took a chance on me because I was a kind of dyed-in-the-wool network hourlong director—but she thought maybe I was more than the sum,” Bray says. “It paid off for her and for me: It kind of reintegrated me into the forefront of youth culture.” Since then, Bray has directed episodes of The Americans, Shameless and Succession.

On set, Bray says he saw how Rae followed through on her ideals in many different ways, including when she fought to film in Ladera Heights instead of pretending the valley was that aforementioned predominantly Black neighborhood. “I believe she wanted to give the location fees to the people she said was representing. The powers that be, the money people, thought that was not the best route to take,” Bray recalls. “But it actually yielded more success because it had integrity to it.”

Over the years, other burgeoning directors would parlay their Insecure experience into bigger projects, including Matsoukas (Queen & Slim), Regina King (One Night In Miami), and Liesl Tommy (Respect). By season two, Matsoukas felt comfortable enough to have prospective directors shadow her to gain experience—including Kerry Washington, who was just beginning to direct for television. The former Scandal star and producer ended up directing two later episodes, and will direct the first episode of a new Hulu show, Reasonable Doubt.

And this season, Rothwell will be making her directorial debut, after four years of studying the craft of filmmaking both as an actor and producer on the show. “[Issa] bet on us, and so we bet on ourselves,” Rothwell says. “She created a safe space for us to take risks, grow and create in ways that the industry at-large very rarely provides POCs.”

The Next Episode

In the past, Black creatives in Hollywood have expressed frustration about finding steady work even after their big breaks, largely because they weren’t considered for non-Black shows, and the number of Black shows was so limited. But now, as Insecure wraps up, it’s hard to find an alumni of the show that hasn’t already dived into another significant venture. Matsoukas has her own production company and recently signed a film deal with MGM. Penny co-created and executive-produced HBO’s Pause With Sam Jay; both he and actor/writer/producer Natasha Rothwell have deals with Disney’s Onyx Collective to create projects for Hulu.

Regina Hicks, a co-executive producer on Insecure, went on to co-create The Upshaws, a breakout sitcom for Netflix this year that has been picked up for a second season. Kindsey Young, the PA-turned-writer, is now writing for Grand Crew, an NBC show helmed by another Insecure alumnus, Phil Augusta Jackson. Deniese Davis founded her own production company, Reform Media Group, which she hopes will nurture the next class of industry changemakers—”the Black female Jerry Bruckheimers and Brian Grazers of the world”—while Aniobi has created Tribe, a networking and mentorship program mostly for writers of color.

Actors on the show now have producing and directing credits on their resumes (including Rothwell and Jay Ellis). The musicians who had their songs featured on episodes have seen career boosts, from Kari Faux to Rico Nasty. “It was early on in my career, and a lot of people watched the ‘Poppin’ music video, and that was like a huge moment for me,” Rico Nasty said in a statement to HBO about one of her songs that made it onto the show.

At the same time, the TV and film landscape has filled up with Black projects since Insecure’s inception, lessening Rae’s burden as a rare Black talent hub. There’s been Ava DuVernay’s Queen Sugar, Robin Thede’s A Black Lady Sketch Show, Lena Waithe’s The Chi and 50 Cent’s Power series—and now joining them is Rap Sh*t, an upcoming HBO Max show based on the ascent of the uber-popular Miami rap group City Girls. Rae herself is executive-producing the show—and this year, she tapped Singleton, Penny’s former assistant, to be a first time showrunner on the project.

“I was so taken aback: I was not prepared for that,” Singleton says of her hiring. Rae, for her part, says that young writers of color should get used to claiming roles they’ve never held before. “They don’t take chances on us: they take chances on white men constantly, based on a little short or something,” Rae says. “Things have changed now that we’re in more positions of power to take chances on each other.”

Singleton is currently filming Rap Sh*t in Miami, and learning on the fly—just as Rae did in the first season of Insecure—while using all the knowledge that she picked up for years working with Rae and Penny. Of course, Singleton hopes to instill their same ethos of uplift and growth. “My assistant is the same age I was when I was Prentice’s assistant—and I spent so much of that time learning from him and writing because he was like, ‘this is the time to be sharpening those skills and finding your voice,’” she says. “My assistant, the PAs and the entire crew: they’re in this environment for a reason, so come ask me as many questions as you want.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com