In November of 1890, a group of women called the Board of Lady Managers gathered in Chicago, a city that had been chosen as the site for the World’s Fair of 1893. The fairgrounds, an area of which was nicknamed (unironically) “The White City,” was to showcase the marvels of electricity and the modern achievements for crowds of Americans and the rest of the world.

In keeping with the mood of the moment, the women were celebrating their own unprecedented victory. The all-male commissioners overseeing the fair granted them permission for a special exhibit—a “Women’s Building”—to showcase the incredible achievements made by American women over the previous decades. The Lady Managers had the task of overseeing what would be exhibited in this building. This could just as well be translated to deciding which women were worthy of being included.

The meeting was full of squabbles, starting from the question of who would be chosen as their leader. While the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued, women’s suffrage was not yet won, and the question of representation wound itself tightly around the issue of politics. Most of the women were, like American women still are, properly dazzled by fantastic wealth, and hence by Bertha Palmer, the wife of a wealthy Chicago businessman who could well be considered the Melinda Gates of her age. Others supported the hardworking, middle-aged suffragist Phoebe Couzins. Palmer ultimately won, not least because her politically minded detractors set about working toward an entirely separate task—collecting money for the erection of a statue of Queen Isabella elsewhere in the fair. In paying homage to the Spanish Queen, who funded Columbus’s expedition, rather than the man himself, they imagined themselves the true radicals.

Squabbles aside, the one thing that all the women, suffragettes and socialites, had in common was that they were all white. Not only were there no Black women on the Board of Lady Managers, the possibility of even including Black women’s achievements was in itself a testy one. No one who was white wanted to talk about race, which they believed was inherently divisive. Instead, they did what boards of organizations excluding Black women still do. They issued a statement. “There should be no discrimination on the score of race and that colored women should have precisely the same chance that white women had, by being given equal opportunity, neither more nor less to do the best work that they are capable of,” the statement read.

When the World’s Fair began in 1893 and the Women’s Building containing thousands of exhibits was inaugurated, the “Afro-American” contribution was limited to a single bound book with statistics about Black women in a table bookcase in the South Record Room of the Building. If a contemporary Black woman was to venture back into the Women’s Building, she would find no representation of herself; all the art and industry of America, it appeared, was the product of the toils of White women only. If a South Asian woman like myself would venture back, she may find herself one of the “40 ladies from 40 nations” that were available to view. Some sang and danced, all could be ranked by their “beauty” in a chart printed in the back of some of the souvenir books at the fair. If you were not the respectable white ladies of the Building, you were simply something for fairgoers’ gaze.

Read more: Feminism Claims to Represent All Women. So Why Does It Ignore So Many of Them?

This history of excluding women is important because it is still so common today. Organizations are filled with white women who, next to white men, wield the most power. Like Bertha Palmer and her cohorts, these powerful white women do not appear to “see” how this exclusion mirrors and replicates their own past experience. In my book Against White Feminism, I highlight just how this refusal to cede any space to women of color propagates “white feminism” which among other things is the failure of white women to recognize the role of white supremacy in leading to white feminist victories. Looking back, it is painfully evident that the social and racial privileges of the women who made up the board overseeing the Women’s Building in the World’s Fair played a tremendous role in providing opportunities toward governance and power. Yet, they saw their position and the selection of the exhibits of almost entirely white women as the products of fairness, as something won on the basis of equal competition.

The competition was not equal then and it is not equal now. A diversity survey released by Deloitte in June 2020 found that white women made the largest percentage gain in board seats in Fortune 100 (15%) and Fortune 500 (21%) companies, bigger than any other group or gender. Undoubtedly, white feminists would point out these gains as victories for “feminism,” when they are really only victories for white feminists who imagine them as justly won.

It is high time feminism had its own racial revolution, but it cannot happen unless the white feminists of today learn from the mistakes of the white feminists of 1893 and cede space so that women of color can be represented and elevated. Feminist solidarity must not be a cover that thwarts discussions of differing racial privilege and hence disparate access to opportunities and achievements. The rates at which white feminists have advanced themselves is marvelous but also tainted by the unearned and unjust fruits of racial privilege that have accrued to them. The time in which America was represented by a “White City” and only white women were good enough to be considered women worthy of celebrating should be relegated to history.

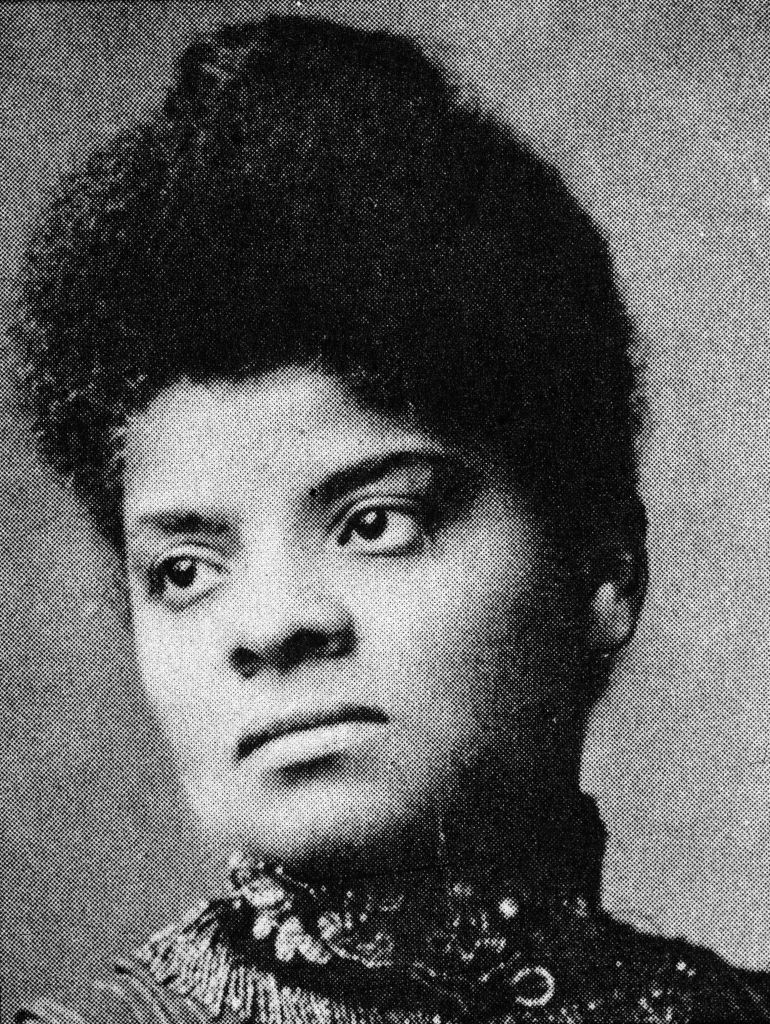

As for the World’s Fair, Black women may not have been in the Women’s Building but they refused to be completely erased from the image of America that the fair was projecting. Black feminist Ida B. Wells (along with Frederick Douglass) published a pamphlet titled, Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. In her diary, Wells recounted that she had personally put at least 10,000 copies of the pamphlet in the hands of visitors during the three months of the World’s Fair hoping that they would get a glimpse of the “real” America. It was “was a clear, plain statement of facts concerning the oppression put upon the colored people in this land of the free and home of the brave,” Wells said.

If Wells were to travel into our time she would likely be disappointed. As of June, just two of the record 41 women leading Fortune 500 businesses were Black. The “real” America Wells fought to expose is still issuing statements about racial diversity while doing very little to enable it. There are now many Women’s Buildings in the United States and Black women are still, for the most part, left out.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com