The night before Julie Rikelman was scheduled to argue before the Supreme Court for the first time, she hardly slept at all. But it wasn’t nerves that kept her up. It was a persistent fire alarm at the Washington, D.C. hotel where she was staying. It went off again and again for hours on end, she remembers, laughing.

Despite the mayhem, Rikelman, the litigation director at the Center for Reproductive Rights who colleagues describe as “unflappable,” stood before the high court the next day to argue the first abortion-related case since Trump-appointed conservative Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh arrived on the bench. She left the oral arguments feeling confident and several months later, she learned she’d tallied up another win. The court sided with the Louisiana abortion clinic that Rikelman represented, holding that the state’s law put an undue burden on those seeking abortions—as was the case when they struck down a nearly identical Texas law in 2016. Abortion rights advocates breathed a sigh of relief.

Most Popular from TIME

But all the drama of that March 2020 argument—which unfolded just before COVID-19 shut the country down—pales in comparison to the pressure Rikelman and the Center for Reproductive Rights are facing now. On Dec. 1, Rikelman will again appear before the Supreme Court to argue against yet another state law, this one from Mississippi, that represents the biggest threat to abortion access that the country has seen in decades.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization centers on a 2018 Mississippi law that would prohibit almost all abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Unlike the Louisiana case that Rikelman successfully argued before SCOTUS in 2020, this law does not add requirements for those providing abortions; it seeks to outlaw the procedure entirely. The Mississippi law represents a direct, unalloyed challenge to the Supreme Court’s 1973 landmark decision in Roe v. Wade, in which the court found that people have the constitutional right to an abortion until the point when a fetus can survive outside the womb, or about 24 weeks into pregnancy.

That the Supreme Court agreed to hear Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization at all came as a shock to Rikelman and her colleagues. But then the news got worse: the Court announced it would not only hear the case, it would consider the question of whether all laws that ban abortion pre-viability are unconstitutional. In other words, the Supreme Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority featuring Amy Coney Barrett in place of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, is prepared to review the precedent of Roe v. Wade itself.

“It’s been clear for 50 years that a ban like Mississippi’s is unconstitutional,” Rikelman says. “If the Supreme Court upholds this ban, it will have effectively overturned Roe v. Wade.”

The case comes at a delicate political moment. In the past year, state legislatures have passed a record-breaking 106 new laws restricting abortion and, in September, Texas implemented the nation’s single strictest abortion law since 1973, banning nearly all abortions after six weeks of pregnancy. The Texas law may also come before the Supreme Court this term. The stakes of this moment, Rikelman says, are “monumental.”

A grounding in human rights

Rikelman has been preparing for this fight for decades. Born in Kyiv, she immigrated to the U.S. with her parents in 1979 after they experienced severe discrimination in the former Soviet Union for being Jewish. Her mother was blocked from medical school because of her religion, and when her parents arrived here barely speaking English, they had to restart their careers from scratch. Rikelman herself learned English as a second language, and says seeing her family’s struggle shaped her interest in civil rights from an early age. “I definitely grew up thinking about how important it was for people to be able to make personal decisions about their lives for themselves,” she says, “and not have the government make those decisions for them.”

In school, Rikelman sometimes felt like an outsider. But in college, she found her niche. She remembers taking a class on sex discrimination that introduced her to Supreme Court cases about reproductive rights. She’d found her calling. She still keeps that college textbook in her office. Some of the cases she reads now in her work at the Center for Reproductive Rights are the same ones she underlined as a 19-year-old. After falling in love with constitutional law, Rikelman clerked for a judge at the Third Circuit Court of Appeals and the first female judge on the Alaska Supreme Court, then accepted a fellowship at the Center for Reproductive Rights, the powerful non-profit that was founded in 1992 to represent the abortion clinic at the heart of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the lesser-known Supreme Court case that upheld the right to abortion that year. After a stint as vice president of litigation at NBC Universal, Rikelman returned to the Center in 2011 and has been there ever since.

In years after the Center for Reproductive Rights was founded, it grew quickly into a legal powerhouse, employing 75 lawyers and wielding a $40 million budget to fight many of the country’s high-profile abortion legal battles, often alongside Planned Parenthood and the American Civil Liberties Union. More recently, its role has become even more outsized. In the decade since Rikelman joined the Center as a senior attorney, the types of lawsuits aimed at abortion access have changed. “We were always fighting restrictions that are burdensome and make it harder to access reproductive health care,” says Nancy Northup, the president and CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights. “But not flat out bans. The boldness of the restrictions, the fact that we are litigating at the Supreme Court the question about whether Roe v. Wade should be overturned, was nowhere on the horizon 19 years ago.”

As the challenges to abortion access have become more pronounced, Rikelman’s experience has accumulated. “Julie has a first rate legal mind. But she doesn’t have a trace of arrogance about it,” Northup says. “It makes her an incredibly effective advocate because she is not letting any kind of ego get in the way of the way that she argues in the courtroom.”

‘Concerning for the rule of law’

For decades, abortion opponents have worked closely with conservative lawmakers at the state level to limit abortion in a variety of ways. They have, for example, put in place an array of requirements ostensibly aimed at protecting patient safety but that really make it difficult for doctors to practice and for clinics to stay open. Abortion rights advocates call those TRAP laws: Target Regulation of Abortion Providers laws. But over the years, efforts to reduce and ban access to abortion have gotten less subtle. Instead of adding facility requirements or mandating hospital admitting privileges—the subjects of the past two abortion-related Supreme Court cases—lawmakers recently have sought to impose gestational bans and to revisit the idea of when life begins. Those laws go straight at the question of whether, and at what point, abortions should be legal at all.

Changing the viability standard, the central holding in Roe, would not only upend the 1973 decision, it would also give states a green light to revisit dozens of other abortion laws that have been blocked over the years. “One of the basic principles of the rule of law is stare decisis,” says Rikelman. “You don’t change precedent unless there’s a really good reason, unless there’s been some really fundamental shift, a real change in facts, a major change in the law—and none of that has happened. For the court to reverse itself here for this right would just be deeply concerning for the rule of law.”

That’s exactly what this Mississippi case is asking the Supreme Court to do. In a brief this summer, Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch asked the Court to overturn Roe, arguing that changes in science and society have rendered the precedent “decades out of date,” and that the controversy over Roe has damaged the Court. “The national fever on abortion can break only when this Court returns abortion policy to the States,” the brief said.

Rikelman and other abortion rights advocates disagree with that logic. If Roe were overturned, abortion would become illegal—either immediately or very quickly—in roughly half the states in the nation. The Center is currently litigating 32 cases and has clients in 25 states. Without the viability line, state legislatures would likely pass more laws restricting abortion and this work would multiply exponentially, Northup says, creating even more unequal access between conservative and liberal states. She notes that the Casey decision opens with the line “Liberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt.” In other words, “the more imprecise the constitutional standard,” she says, “the more that opens the door for chaos and thus no refuge, no safety, no guarantee of liberty.”

‘Always another road to go down’

Texas’s recent, ultra-strict abortion law represents a cautionary tale for the abortion rights movement. The law not only bans most abortions, but also deputizes private citizens to enforce the ban and gives them a bounty to do so. Some clinics in the state have stopped offering abortion services altogether, while the law has forced other abortion providers into tough legal corners. In the weeks since the law passed, Texans have flood surrounding states in search of abortions. “Texas has given us a preview of what we could see on a much bigger scale in many states around the country if Roe is overturned,” Rikelman says.

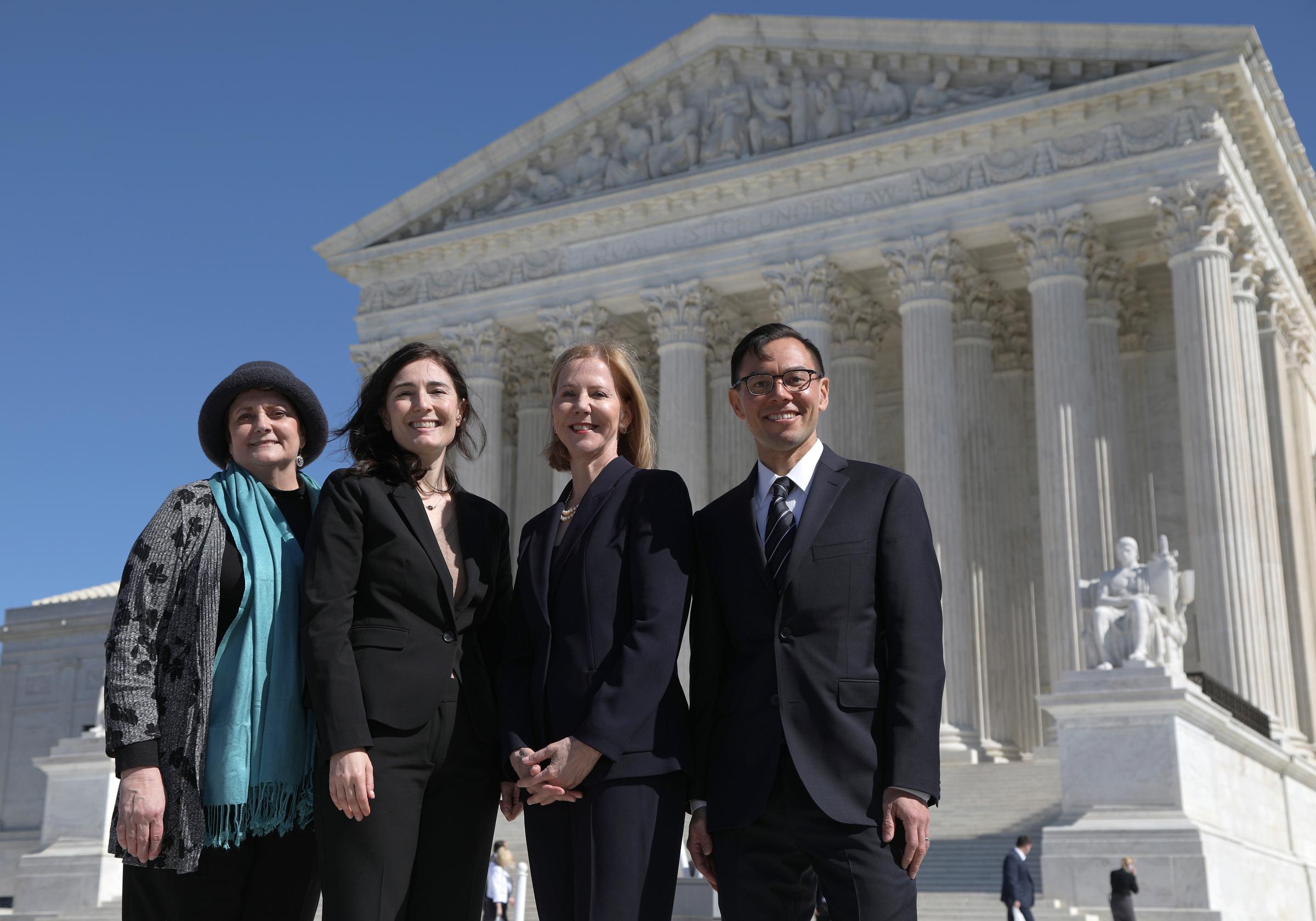

She knows that her ability to argue effectively before the Supreme Court in December comes with huge stakes. Women still make up only a fraction of advocates before the Supreme Court—often less than 20%—and now Rikelman will be appearing again in a case that could have historic implications for the future of how women are able to live in the U.S. She and her co-lead counsel Hillary Schneller often work 13- or 14-hour days preparing for oral arguments. By the time Dec. 1 comes, their team will have spent thousands of hours on the case.

The arguments themselves will look very different from the past. Due to the ongoing pandemic, only the main lawyers from each side and press will be allowed inside. Everyone else, including Northup, will have to wait outside. Rikelman isn’t even sure her husband will make it this time, as the family has been careful about traveling since their younger daughter isn’t yet eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine. Rikelman plans to listen to music—maybe some U2—to steady herself before the arguments and meditate on the extraordinary work that her clients do to keep their clinics open.

She and Northup are realistic about the outlook for their cause. The Supreme Court already allowed the Texas law to go into effect earlier this fall, and despite the Justices recently professing that they want to remain apolitical, the conservative Justices have all expressed clear opposition to abortion over the course of their careers.

“I have never been as concerned about the constitutional protections for abortion rights as I am today,” Northup says.But, she adds, she remains optimistic about the fight for abortion access going forward. “There’s always another road to go down,” Northup says. “If the Supreme Court slams the door, reverses Roe vs. Wade, we have the U.S. Congress, we have fighting state by state. We have mobilizing people, like perhaps had not been necessary before.”“There is always, always an opportunity to fight on a different front,” she adds. “And that’s what we’ll do.”

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the daily D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com