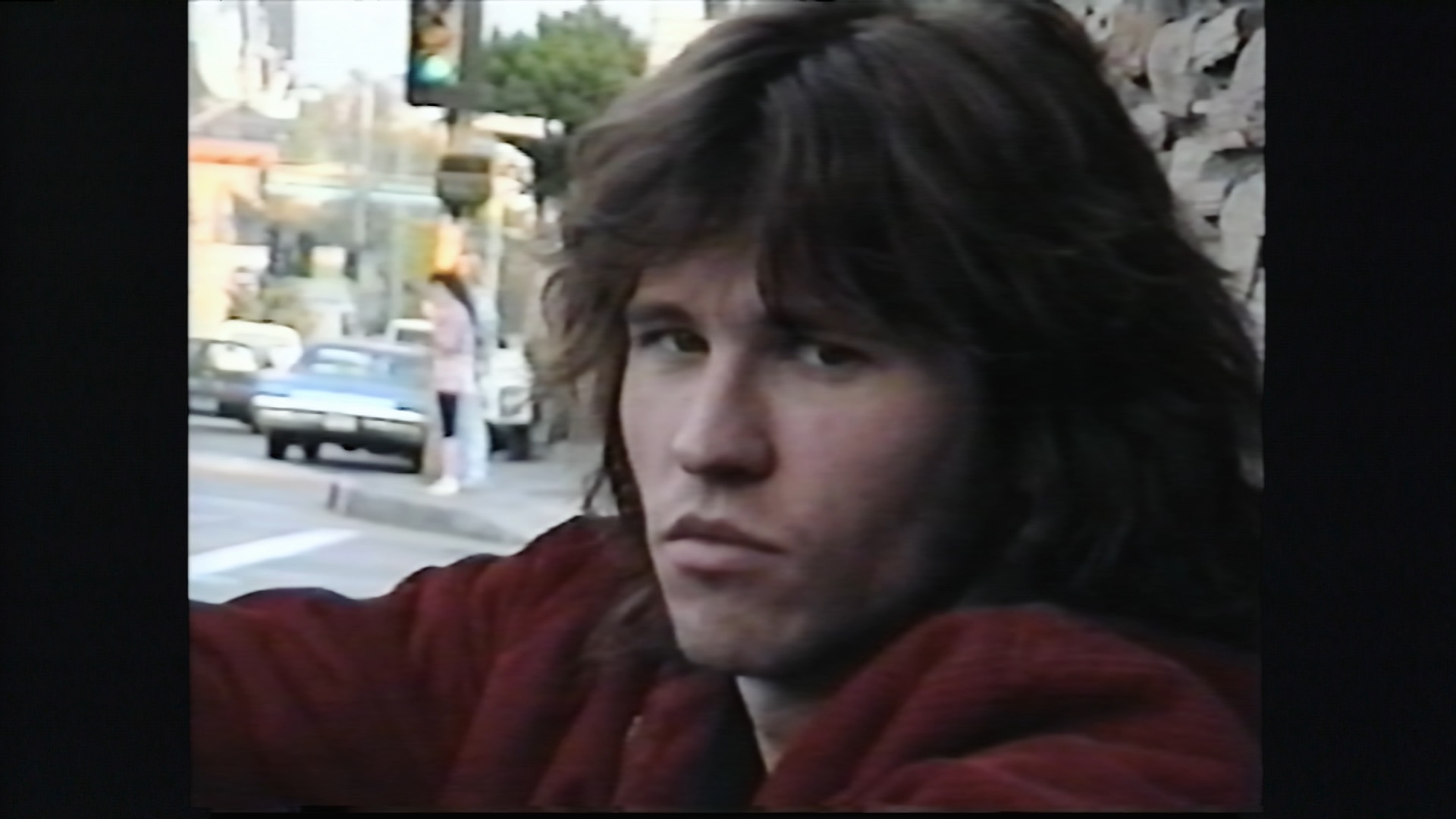

Now that we’re used to recording our whole lives on cell phones, it’s hard to imagine an era when we didn’t walk around with mini movie cameras in our pockets. In the early 1980s, Val Kilmer—who would go on to give vibrant performances in movies like The Doors (1991) and Tombstone (1993)—became an early adopter of video recorders. Footage Kilmer shot through the years—plus some from the present, as well as home movies from his childhood in Chatsworth, California—provides the backbone for the documentary Val, directed by Leo Scott and Ting Poo, which draws us deep into the life and career of a bold and sometimes headstrong performer.

Kilmer got his first Broadway role after graduating from Juilliard, playing third banana to Sean Penn and Kevin Bacon in 1983’s Slab Boys. Backstage footage from that lark shows three beautiful, boisterous young men, practically kids, who have no clue how their careers are going to unfurl. But Val also shows us Kilmer at an even earlier age, as a precocious kid appearing in home movies with his two brothers, some of them re-enactments of films the boys loved—including an homage to Jaws, featuring a fine, salty Robert Shaw impersonation from the young Kilmer.

The wrenching footnote to these delightful clips is that the mastermind behind them, Kilmer’s younger brother Wesley, died at age 15 in a drowning accident, an event that marked the family forever. And although Val leans heavily toward flattering its subject, some of Kilmer’s own video recordings cast him in a decidedly unflattering light: we see him sassing back as director John Frankenheimer tries to keep order during the filming of the ill-fated 1996 fantasy adventure The Island of Dr. Moreau, which Kilmer saw as his big chance to work with one of his idols, Marlon Brando. While it’s often hard to pinpoint what makes a film a disaster, unruly actors rarely help.

Yet Val, equal parts swaggering and wistful, keeps us squarely on Kilmer’s side, suggesting that if he was ever difficult on set, it was only because he cared so much about every project he took on. This deeply personal scrapbook is particularly resonant now that Kilmer’s career has been curtailed by throat cancer; he can speak, but he is still learning how to shape sounds. (Much of the documentary is narrated by his son, Jack, reading words written by Kilmer.)

Read more reviews by Stephanie Zacharek

Footage of Kilmer today, slightly puffy and arrayed in turquoise-and-silver jewelry, shows him signing Batman memorabilia at Comic-Con—a detail that could be stinging, considering how much Kilmer hated making his single entry in the franchise, 1995’s Batman Forever. Yet Kilmer, speaking in his own voice, says he doesn’t mind these events; he’s grateful that people still care. Val is a portrait of an actor who poured his all into his work. Only now can he see what it amounts to, and find some vindication in the truth that it was worth defending all along.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com