Twenty years ago, on July 20, 2001, a film that would become one of the most celebrated animated movies of all time hit theaters in Japan. Directed by Hayao Miyazaki and produced by Studio Ghibli, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, titled Spirited Away in English, would leave an indelible mark on animation in the 21st century. The movie arrived at a time when animation was widely perceived as a genre solely for children, and when cultural differences often became barriers to the global distribution of animated works. Spirited Away shattered preconceived notions about the art form and also proved that, as a film created in Japanese with elements of Japanese folklore central to its core, it could resonate deeply with audiences around the world.

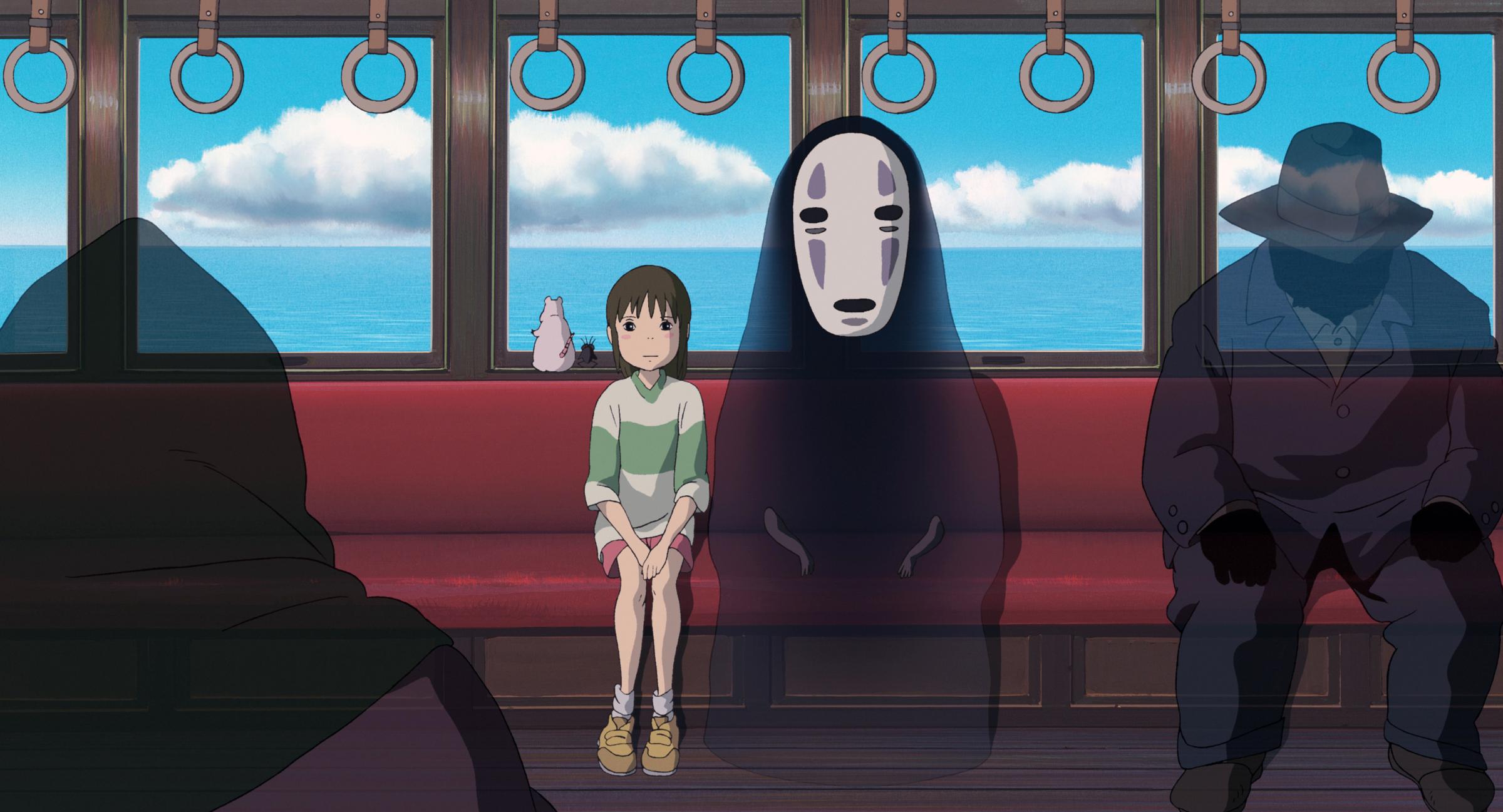

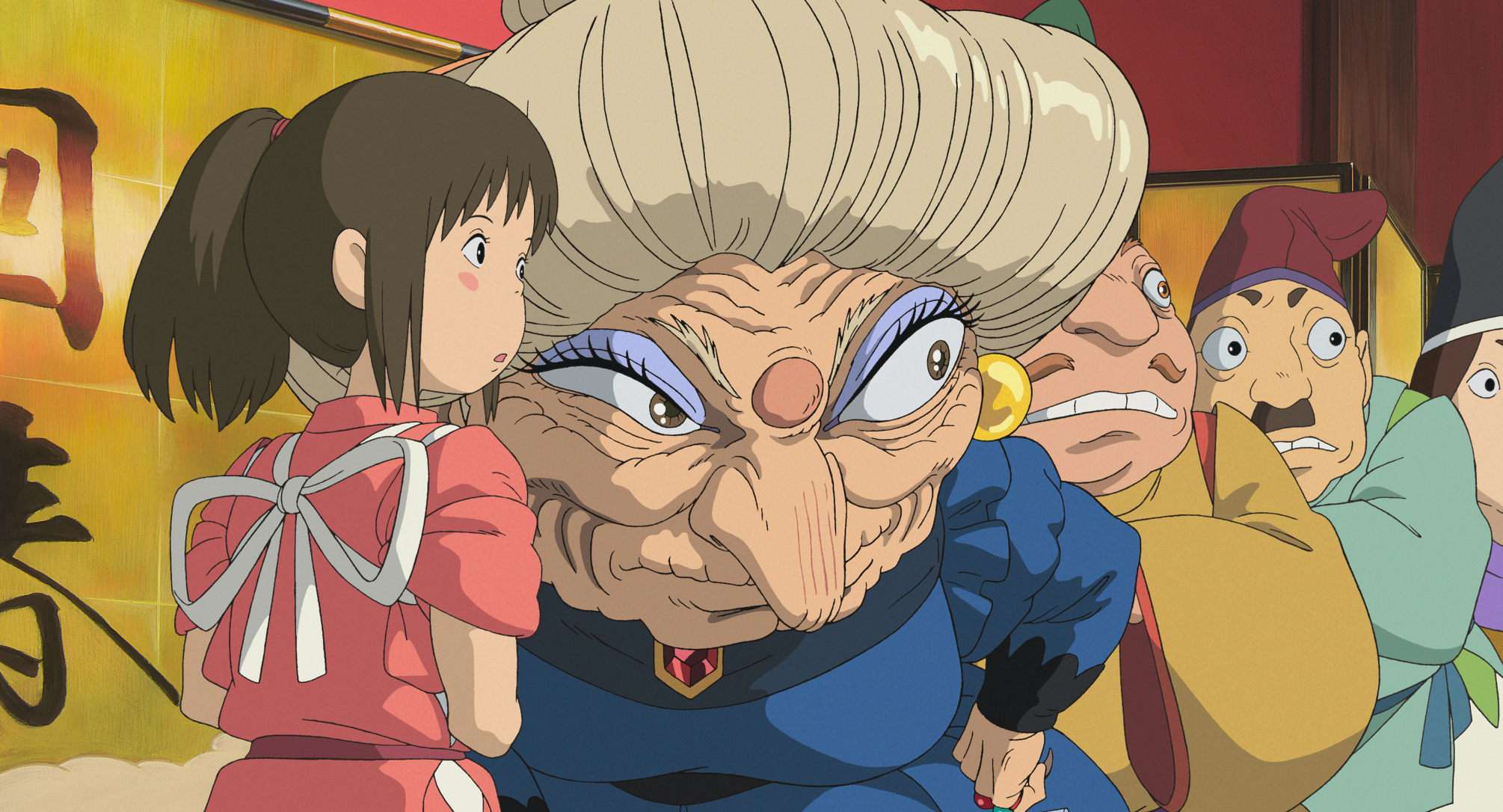

The story follows an ordinary 10-year-old girl, Chihiro, as she arrives at a deserted theme park that turns out to be a realm of gods and spirits. After an overeating incident leads her parents to turn into literal pigs, Chihiro must work in a bathhouse that serves otherworldly customers in order to survive and find a way to return home.

Imaginative and inspired, Spirited Away immerses the viewer in a fantastical world that at once astounds and alarms. Many of the deities are based on figures in Japanese folklore, and part of the Japanese title itself, kamikakushi, refers to the concept of disappearance from being taken away by gods. The story is also a tale of resilience and persistence, as Chihiro gradually draws on her inner strength to endure this land where humans are designed to perish.

In a 2001 interview with Animage, Miyazaki said he had an intended audience in mind for the film. “We have made [My Neighbor] Totoro, which was for small children, Laputa, in which a boy sets out on a journey, and Kiki’s Delivery Service, in which a teenager has to live with herself. We have not made a film for 10-year-old girls, who are in the first stage of their adolescence,” he said, as translated by Ryoko Toyama. “I wondered if I could make a movie in which they could be heroines.”

Spirited Away would go on to resonate far beyond its target demographic. Immediately upon release, the film broke the opening weekend record in Japan by earning $13.1 million over three days. It beat previous numbers set by another one of Miyazaki’s films, 1997’s Princess Mononoke. Spirited Away went on to become Japan’s highest-grossing film of all-time, and held the record for 19 years, surpassing $300 million at the local box office last year after the movie was re-released. (It was eclipsed soon after by Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train in December.) .

In the years following Spirited Away’s premiere, the film traveled widely as it was screened at international film festivals and released theatrically around the world. In 2020, it became available to even more audiences when it entered Netflix’s catalog in dozens of countries and joined HBO Max’s catalog in the U.S. when the platform launched with a Studio Ghibli collection. Two decades later, the story of Chihiro continues to reach new audiences, including through new formats: a stage adaptation of Spirited Away directed by John Caird (Les Misérables) and produced by the Japanese entertainment company Toho, which originally distributed the Miyazaki film in Japan, is set to premiere in 2022.

For its 20th anniversary, TIME looks back at Spirited Away’s historic path from Japanese blockbuster to Oscar winner, its U.S. release by Disney following a complicated history between Miyazaki and foreign distributors, and the film’s lasting impact on Japanese animation and beyond.

The significance of Spirited Away’s box office records and awards

Spirited Away raked in $234 million, overtaking Titanic to become Japan’s highest-grossing film. Its commercial success helped make animation “a very significant, legitimate film genre in Japan,” says Dr. Shiro Yoshioka, a lecturer in Japanese Studies at Newcastle University’s School of Modern Languages and author of the chapter “Heart of Japaneseness: History and Nostalgia in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away” in Japanese Visual Culture. He explains that its popularity had a compounding effect on that of another Studio Ghibli release from four years earlier. “Princess Mononoke was already successful and put animation on the map in Japan,” he says of the 1997 film that was Japan’s box office leader before being unseated by Titanic. “Until then, animation or anime was more like a niche genre,” Yoshioka explains

Dr. Rayna Denison, who wrote the chapter “The Global Markets for Anime: Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away” in Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts and is a senior lecturer at the University of East Anglia, says that while Studio Ghibli films had been growing in Japan’s box office since Kiki’s Delivery Service was released in 1989, Spirited Away was able to reach blockbuster status—surpassing records previously set by movies like E.T. and Jurassic Park. “It’s a major shift in the local market proving that films from Japan could be the equivalent of, in blockbuster terms, big Hollywood movies,” Denison says.

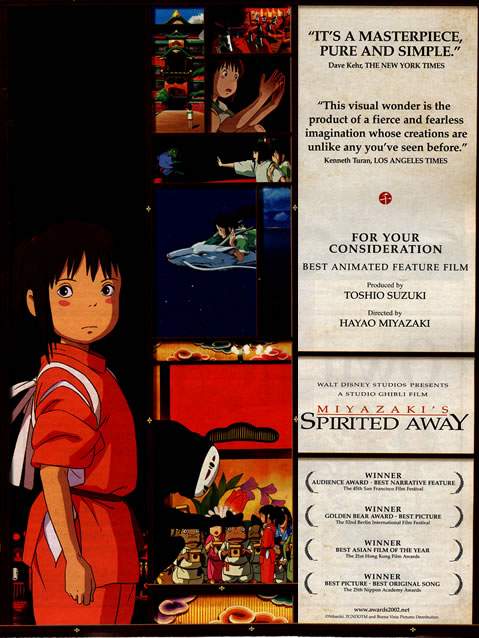

International critical acclaim soon followed the film’s domestic commercial success. At the 2002 Berlin International Film Festival, Spirited Away was a co-recipient of the Golden Bear, the first animated feature to win the highest prize in the festival’s history. In 2003, Spirited Away was awarded Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards, becoming the first—and to this day, only—non-English-language movie to win the award.

“The fact that a non-Western, Japanese animated film would win major awards from two major Western sources was a very big shot in the arm to the Japanese animation industry,” says Dr. Susan Napier, author of Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art and a professor at Tufts University. There was also special significance to Spirited Away taking the Oscar win during only the second year after the Best Animated Feature category was created. (Shrek was the first movie to win the category.) “For so long, cartoons have been seen in the West—America in particular—as kind of childish, vulgar, things that you didn’t take seriously,” Napier explains. When Spirited Away took home the Academy Award, Napier says, “people were starting to say, wow, what’s all this about animation that it’s getting its own category, that it’s considered a real art form.”

According to Yoshioka, the Oscar win was hugely important for Miyazaki, Studio Ghibli and Japanese animation more broadly. “It made Japanese animation a more global film genre rather than very niche,” he explains, noting that animation was no longer perceived to be content strictly for otaku, a term often used to describe passionate fans of Japanese culture who heavily consume entertainment like anime and manga.

Disney’s partnership with Studio Ghibli and the complicated history behind it

A major component of Spirited Away’s global popularity was the partnership between Tokuma Shoten, then the parent company of Studio Ghibli, and Disney. Forged in 1996, the agreement gave Disney the home video rights to a handful of Studio Ghibli films in addition to the theatrical rights for distributing Princess Mononoke outside of Japan. Disney would later acquire the home video and theatrical rights to Spirited Away in North America.

But this partnership had a rocky history. Miyazaki was wary of foreign distribution for his films after the director’s 1984 movie Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was infamously edited by Manson International for its U.S. release. A full 22 minutes were cut from the original film, and it was promoted as Warriors of the Wind with posters featuring male characters who do not appear in the movie.

“The distributors edited the film in such a way that it’s become almost like a kind of children’s adventure story, there’s no nuance,” says Yoshioka, noting that the movie, which follows the heroine Nausicaä in a post-apocalyptic world, has a layered plot. “The assumption behind the editing was that American audiences wouldn’t understand the storyline, because in the States and in many Western countries, the assumption was that animation was for children.”

The heavy editing of Nausicaä was part of the reason why, when the U.S. release for Princess Mononoke was in the works, Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki sent Harvey Weinstein—who led Miramax, which was handling the film’s American distribution—a samurai sword with the note, “no cuts.” The movie hit U.S. theaters in its uncut form in 1999, but did not perform strongly at the box office—grossing $2.3 million for the initial release. Napier says it’s hard to pinpoint why the film didn’t quite catch on. “Maybe at that point people weren’t quite ready for it. It was another kind of dark film, it had an ambiguous ending,” she says. “It also doesn’t have a conventional good-versus-evil kind of plot which American audiences tend to expect.”

By the time of Spirited Away’s limited release in the States in 2002, Napier says that Disney was more familiar with Miyazaki as a brand. Another major difference from Princess Mononoke was that Pixar’s John Lasseter, who had long been a fan of the Japanese director, was at the helm of Spirited Away’s distribution and English adaptation efforts. “That kind of industrial support from people in America that were, at the time, very well respected in the animation world was really important to raising Miyazaki’s profile, raising the profile of Studio Ghibli,” Denison says. Lasseter and Disney boosted Spirited Away’s visibility in America by heavily campaigning for the film to be considered for the Academy Awards, including with a full-page advertisement in Variety. “They were very, very careful to push the film to the foreground to keep it in everybody’s minds,” she says. “And I think, in no small part, that’s one of the reasons it succeeded and won the Best Animated Feature.”

Drawing in $10 million, the film did not see huge success in U.S. theaters. But Yoshioka says that, in contrast to Princess Mononoke, it was the first Studio Ghibli movie to reach a broader American audience. It also attracted significant viewership beyond the U.S, grossing around $6 million in France, for instance, and more than $11 millio in South Korea.

How Spirited Away influenced animation

Spirited Away is not just the only non-English-language animated film to have won an Oscar for Best Animated Feature, it’s also the only hand-drawn animated film to receive the honor. Nearly all of the other winners are computer-animated works. “Spirited Away comes at a time when there’s a big changeover happening in Japanese animation, and more and more people are using computers rather than traditional two-dimensional, cel-based animation,” Denison says, referring to the technique in which every frame is drawn by hand. The film incorporated computer animation, but sparingly.

“As a viewer, it’s very subtle and nicely done. It still looks like 2-D, more traditional film animation,” says Dr. Mari Nakamura, a lecturer of modern Japanese studies and international relations at Leiden University. “This is very characteristic of Japanese animation in general—how to have a good balance between 2-D and 3-D.” And while many studios have left behind two-dimensional animation over the decades, the style has remained core to Studio Ghibli’s style. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly last May, Studio Ghibli’s Suzuki talked about the hand-drawing process for Miyazaki’s upcoming film, How Do You Live? “We have 60 animators, but we are only able to come up with one minute of animation in a month,” he said. “That means 12 months a year, you get 12 minutes worth of movie.” It’s a painstaking process, but one that has undeniably shaped the singular animation aesthetic of Miyazaki films.

There is, indeed, plenty to think about in Spirited Away for audiences of all ages. Napier says that in addition to the aesthetic impact of the film, there has also been a psychological one. “This willingness to see children in a dark and scary world, the possibilities of children having to confront dark and scary things on their own,” Napier says, “A number of anime were already dealing with it before Spirited Away, but I think after that it becomes even more of an important motif in Japanese animation.”

She draws similarities between Spirited Away and Makoto Shinkai’s 2016 film Your Name—Japan’s fifth highest-grossing movie of all time—which tells the story of two high school students, one boy and one girl, mysteriously swapping bodies. “Both stories, although they’re very different, really are about young people confronting very strange, destabilized worlds,” Napier says. Like Chihiro, whose name is taken away by the sorceress Yubaba and becomes “Sen” as she begins work in the bathhouse, the characters Taki and Mitsuha in Your Name lose their identities through the body switches. Napier hypothesizes that these themes relating to uncertainty are connected to a dominant feeling in the 21st century of children being more on their own and feeling at a loss. “I think one reason why these films are so popular is that they do recognize and acknowledge that the world can be scary, and that we don’t always know what’s going to happen to us,” Napier adds.

Outside of Japan, Miyazaki has inspired filmmakers from Wes Anderson to Guillermo del Toro. In the case of the latter, Napier says that there are clear similarities between Spirited Away and del Toro’s 2006 live-action fantasy Pan’s Labyrinth. That movie’s main character, 10-year-old Ofelia, is taken to the countryside to a new home like Chihiro was. Napier describes a scene in Pan’s Labyrinth’s opening sequence, in which Ofelia gets out of the car and enters the forest, as a direct homage to Spirited Away. “She sees a kind of stone image that is so overtly similar to an early scene in Spirited Away when Chihiro confronts a stone image,” Napier explains.

And while not specific to Spirited Away, Pixar’s Lasseter—who directed films including Toy Story, Cars and A Bug’s Life and in 2018 left the company after allegations of sexual misconduct—has long spoken of his admiration for Miyazaki’s works. In Toy Story 3, the character of Totoro even makes a cameo as a plushie. Napier points to a later Pixar film that she thinks “really clearly shows influences from Spirited Away”: the 2015 movie Inside Out. “It’s about a young girl who is, as with Spirited Away, leaving her old home for a new one,” Napier says. “She’s being confronted by a variety of challenges and emotions.” Napier adds that it’s another example of a female protagonist carrying the film, something that has only become slightly more prevalent in the last decade after Pixar’s history of centering male protagonists.

Spirited Away embaced as a classic, 20 years later

As Denison puts it, “This is a film made by a master animator at the height of his powers and it is one where the quality of the animation really does set it apart from everything else around it. Nobody else was making films that looked like this or that were as inventive as this was at this time.”

To Yoshioka, one reason why Spirited Away continues to be adored two decades after its release is its ambiguous nature. “It’s not entirely clear when watching for the first time what the story is about,” he says, adding that earlier Miyazaki films often had clearer themes. Spirited Away can be interpreted in numerous ways by the viewer. “This sort of elastic or enigmatic feature is key for the film to be loved as a classic,” he says. In this way, even 20 years on, Spirited Away is a movie that can be watched and rewatched, pondered in solitude or mulled over in company, the film’s meticulously crafted and intricately designed visuals washing over you with each new viewing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com