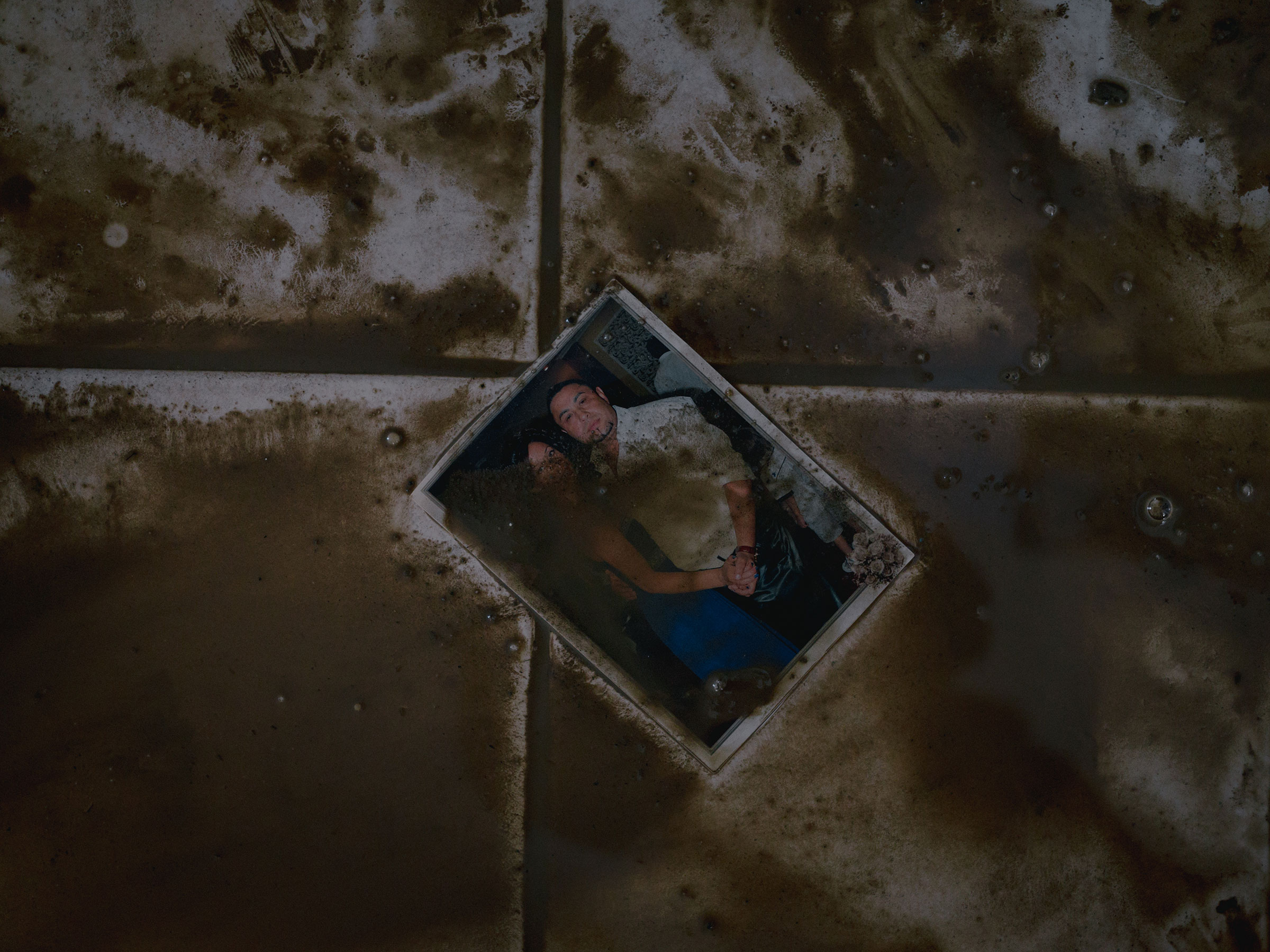

Pia Negro’s family has lived in the same castle in Blessem, western Germany, for 300 years, and spent the last 30 years restoring it to its former glory. But around 4am on Thursday, they were forced to leave it in minutes. Firefighters yelled to them from outside saying that they needed to evacuate, as floodwaters rushed towards their home. “We couldn’t bring anything—not the very old furniture, not even photos that are highly emotional, just our phones,” says Negro, 32.

Like many in Germany and neighboring countries, Negro hadn’t anticipated just how bad last week’s floods would be. She and the castle’s 40 inhabitants, including her entire family as well as renters, spent Wednesday moving furniture to higher floors, and went to sleep once the rains had stopped in the evening. But as they slept, the muddy waters continued to rise in Blessem and a nearby dam threatened to break. Soon after the residents evacuated, the castle and the surrounding village were submerged entirely by muddy water. The building remains inaccessible, Negro says, and the family has launched a crowdfunder to try to save it. “We are just in shock that something like that can happen to our home.”

That sense of shock is shared by many Northwestern Europeans. Accustomed to robust governance and a mild climate rarely troubled by the extremes of weather they see on the news, few were prepared for the scenes they saw this week after the worst flooding to hit the region in centuries.

“People kept saying it was worse than the war,” says Arne Piepke, from the DOCKS photography collective, which captured the scenes in western Germany—the center of the flooding. War was the best analogue locals could think of for the death and destruction wrought by the weather, he says. “This just hasn’t happened here before.”

More than 7 inches of rain fell on parts of the western German states Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia between Tuesday and Thursday— roughly double the normal expected rainfall for the whole of July, causing major rivers to burst their banks and sweep away entire villages.

At least 160 people died in Germany and 31 in Belgium, and more are missing. Some 370 miles of railway tracks were damaged. “The German language has no words, I think, for the devastation,” Merkel told reporters as she surveyed the damage in Schuld, a town on the River Ahr.

It will need one. Developing countries have long borne the brunt of extreme weather events, especially those with few resources to deal with them. In Madagascar, for example, the worst drought in 40 years is currently pushing 400,000 people into famine. But the summer of 2021 is showing us that nowhere is safe in the climate change era. In June, a normally temperate village in western Canada briefly became one of the hottest places on earth and before 90% of its buildings were razed by a wildfire. Dramatic—though far less devastating—disruption also visited New York and London this month, when several inches of rain fell in a few hours, gushing into subway systems and leaving shocked commuters to wade through waist-deep dirty water.

Survivors of the floods in Germany are reeling from the loss of a sense of relative safety in the face of climate change. “We live in a society that thinks it can control nature. And now people are feeling powerless against it,” says Albi Roebke, an emergency chaplain from the city of Bonn, deployed by the government to counsel hundreds of survivors in North Rhine-Westphalia over the past week. “We have to be afraid of water and fire, like our ancestors 40,000 years ago. That’s very difficult for people to understand.”

A sense that wealthy countries with typically mild climates won’t really be affected by extreme weather may have made the death toll worse in Germany. Some have criticized the effectiveness of warning systems in the affected states, arguing they didn’t communicate the seriousness of the rainfall, which meteorologists had flagged early last week, to the public. “We could have been warned much earlier,” Negro says. “Nobody was aware of how severe it would be.” In at least four instances, people drowned in their basements, some of them trying to save their belongings, rather than flee.

“People thought ‘yeah, I guess it’s going to rain a lot.’ But they don’t know what that means,” says Karsten Haustein, a climate scientist and meteorologist at Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), a research center. “We have to get rid of this thought that somehow extreme and severe weather cannot impact us—this is the climate hubris we have going on in Europe.”

Studies will need to be done to determine whether or not these floods would have taken place without climate change. But scientists say it is safe to assume that it wouldn’t have rained so much, for so long, without the warming of the planet. For one thing, warmer air can hold more moisture—7% more for every 1°C increase in temperature—and Germany’s average temperature has risen by more than 2°C over pre-industrial times.

Another factor that might have played a role is the slowing of regional air currents as the difference in temperature between the polar regions and the equator decreases, meaning low pressure systems can stay in one place for a longer time. In western Europe this week, that might have allowed the rain to fall on the same place for longer. A similar effect led the intense “heat dome” system to linger over western Canada for a perilously long time in June.

With climate change, Haustein says, “at some point, an event which would have been just heavy rainfall without too much damage is suddenly a really catastrophic event. That threshold will simply be crossed more often.”

Europe has done more than most regions to recognize the risks of climate change and step up efforts to fight it. In the same week that the floods hit, the E.U. presented its plan to drastically overhaul its economy to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Germans themselves are even more concerned about climate change than other European citizens, according to regional polls, and the country’s Green Party is projected to make significant gains at its September elections.

But even the most drastic efforts to cut carbon emissions—which face huge barriers to success—will not reverse the destabilization of our climate that we are beginning to see. A certain amount of further warming is already baked into our future, since carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for at least 300 years, and will keep trapping more heat. As a result, scientists warn that recent weather events are not a “new normal” but the end of any kind of normal or stable climate altogether.

For that reason, experts say governments urgently need to widen their focus to include adapting to that instability—as well as emissions cuts—in the coming months and years. Adaptation will mean costly efforts to make homes, transport and infrastructure much more resilient to heat, rain and droughts. It may also mean expanding and formalizing our systems for cleaning up after disasters. At the very least, it means better warning systems and more public awareness that extreme weather is a real threat—whichever country you live in.

Photographs are by members of DOCKS, a collective of five documentary photographers: Aliona Kardash, Maximilian Mann, Ingmar Björn Nolting, Arne Piepke and Fabian Ritter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Ciara Nugent at ciara.nugent@time.com