From the time he was sixty until he died, my dad lived on a ranch where, instead of using money to pay rent to the white couple who owned and lived on the property, he worked and helped to manage the land.

They shack they offered him in exchange for his labor was down a dirt road, and had a cement floor and holes in the walls. There were problems with it in every season. December rain, March wind, and smokey September heat all pushed inside. Rodents loved it. There was no refrigerator. There was no water. There was no electricity, just a generator as-needed and its grizzly hum, hooked up to the space heater or his breathing equipment.

The landlords sometimes called him the Big Nig. Six-foot-four, big-boned, Black. It did not strike me as incidental to the decrepit housing they provided, or the labor by which he paid for it. He laughed about the nickname, though. And I laughed when he told me; that seemed to be the reaction he wanted. But it made me want to spit in their faces. I was rude to them when I visited, aware that my iciness didn’t serve my dad, who relied on the economy he and the landlords had created.

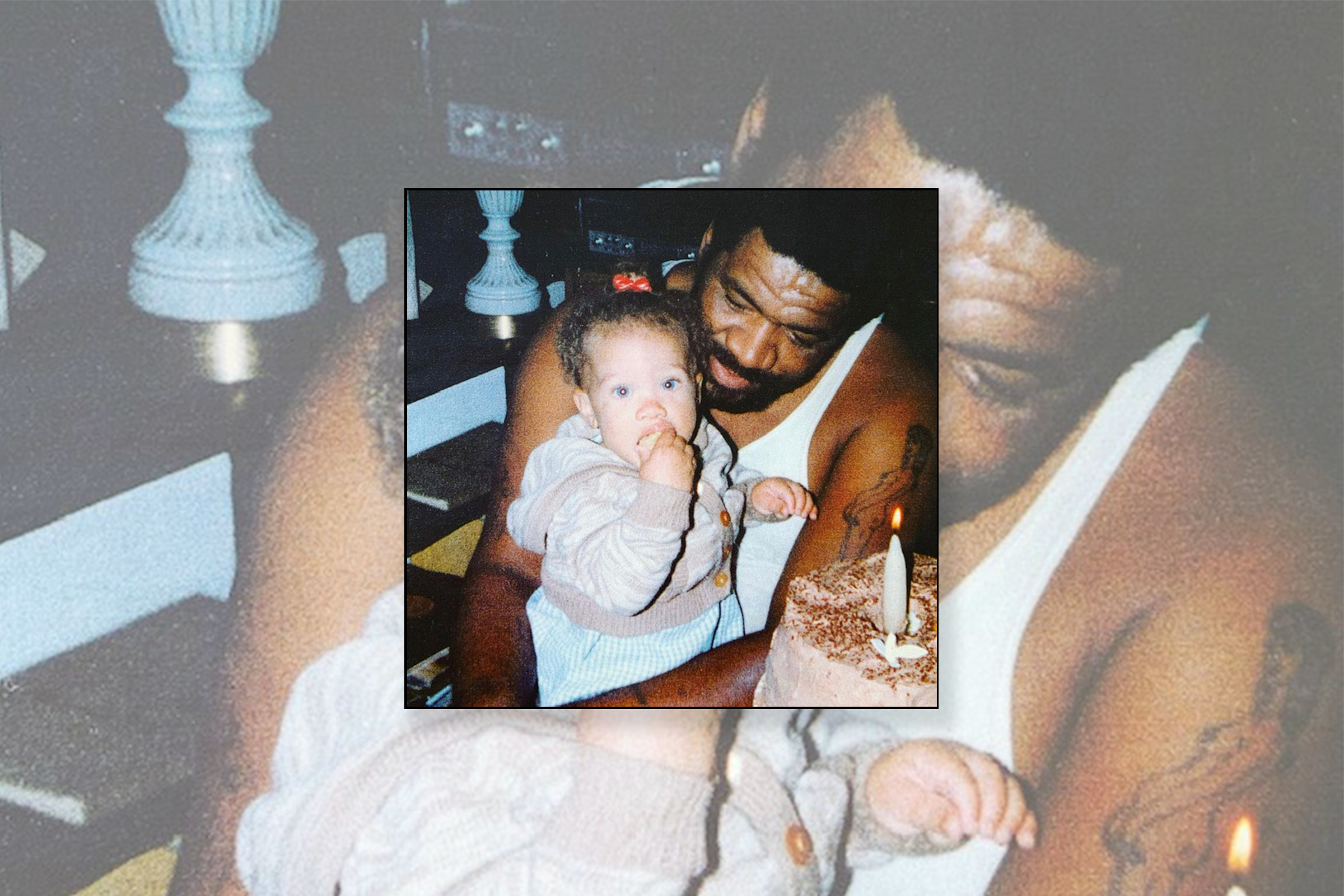

My dad chose this—or was forced to choose it—because, after nearly two decades in prison, he needed the quiet space of the land, and because he could use his labor to pay his primary living expense. He was first incarcerated at seventeen, and left prison for the last time around forty, a few years before I was born. Prison shaped the rest of his life, molding his innate appreciation for nature and stillness into a deep (crippling?) need for solitude and space. It also severely limited the kinds of expectations, exchanges, and rules—what you might call norms of society—he could tolerate. It made him unable to sit with his back to the door. It made him hypervigilant; there would be a sound on the street—a car backfiring, a neighbor hollering briefly—and he’d startle, suddenly focused on the window or the door, no longer in the room with us. It made him shop for food at 2 a.m., when the grocery store was empty. It made him wary of the emotional sways and eddies that comprise family life in a house. It made it harder to hold down jobs, which he’d have to do to pay rent with money.

As he got older—into his seventies—I tried to help him leave the ranch, or tried to try; in retrospect, my efforts were half-hearted because, though I felt guilt and shame that my dad lived that way, I was ambivalent about what it would take to help him. He had no money and could not hold a traditional job anymore, though, when I was a kid, he managed to work periodically as a bakery’s truck driver, or doing set-up work for a caterer, or construction, or selling drugs. We offered to buy him a trailer or have him move in with us, but he refused. He was so deeply acclimated—institutionalized—to a decrepit domesticity, to something most people would call uninhabitable, that it seemed likely he’d be more physically and psychologically comfortable in our basement than in our house. So we offered him that, as strange as it might look to other people. But he wasn’t interested.

He wanted to stay where he was. Or he couldn’t imagine being anywhere else. There, unlike in prison, he could be left alone, physically distant from other people and their needs, whims, power trips and pain. He could relish his own sense of time, his own rhythm, unlike in prison. He was swimming in nature—ladybugs and rabbits, vegetable gardens and citrus trees, puddles and creeks, daylight and the sky—unlike in prison. His favorite thing to do was “set”—meaning, sit and watch the peace of his sweet corner. I’d call him and say, “Watcha doin pops?” He’d answer, “Oh, I’m just settin here, watching the wind.”

He must have known that the solitude of that place meant he might die alone, and perhaps slowly, if he had a bad fall or accident when his landlords weren’t around. He knowingly traded the safety and normalcy most of us rely on for a kind of freedom he’d rarely had. And he did die alone.

The coroner said it was probably quick—a heart attack, maybe. But within hours of getting the news, I asked myself whether it wasn’t racism, slow and steady, that killed him. Whether but for its grip on his shoulders, but for being trapped in its wake, he might have had a better death.

Because here’s what happened: his truck hadn’t moved in days, though every morning he drove it across the property to check the land. He wasn’t answering his cell phone, though it was always clipped to his t-shirt. And he was eighty years old, with diabetes, congestive heart failure and C.O.P.D. His landlords—inventors of that nickname, the Big Nig—knew all of this. They knew his health status, they knew his truck hadn’t moved, and they knew he wasn’t answering his phone, because they’d seen the truck stationary all week, and they’d tried calling him, too. After three days, they sent their son to my dad’s shack; he noticed the unlocked door and called, “Lee?”. When no one replied, he simply left. Three days later, the landlady finally called my mom to say, “I think something might be wrong with Lee.” She explained that he hadn’t answered his phone or moved his truck in a week, and his door had been unlocked for days. The landlady said, “Do you think I should check on him?” My mom hollered, “Yes!” The landlady said, “But I’m scared!” (Of what? His body—large and black and male—even in death?) The landlady refused. I cannot separate any of this from how they called him the Big Nig. My mom drove to the ranch, opened the shack door, and saw his body. The coroner said he’d died six days before.

On my dad’s side of the family—the Black and brown side—the state and its violent power are never far away. The state draws us into an intimate, involuntary relationship, and we’re never fully at ease. It often feels like, beneath the thin layer of our free-will, the state is the decider, the key-holder, the vault from which our limited choices are drawn and into which our histories are thrown, like a grave. The state has always had a grip around my dad’s family—and had its grip on him until the moment he died.

(I sometimes wonder what it’s like to experience life without the state’s hands on you like a battering ram in constant motion. And then I remember. I can see what it’s like to be free of the state: the white side of my family is free, and nearly always has been.)

In the early 1950s, my teenaged dad walked into a bank with a pistol and walked out with over $100,000. There was no money on him when he was arrested, and no money ever found. He didn’t want his mom to know he’d been arrested so he told the police he was an orphan. He looked big for his age, and he successfully concealed the fact that he was a minor. He was convicted and sent to Soledad State Prison, a prison for adults. For the next twenty years, he’d be released, then sent back (San Quentin, Folsom), convicted of other robberies and burglaries. I often asked him about his time in prison, hoping he would illuminate that black hole of years because I longed for the fullest possible understanding of him, for the most detail I could get. But he rarely answered my questions, and always reluctantly, preferring and perhaps needing to leave those years in the dark.

I know my dad made choices that incarcerated him—and I also know that as a poor, big, black man born in 1938, his options were few. Southern California, where he was born, was not the deep south—but it was no utopia. Public spaces from fire stations to beaches, from bars to hotels were segregated. Gangs of white people were setting fire to black people’s houses, burning crosses on their lawns. The so-called Zoot Suit Riots and the Second Great Migration were on deck. Redlining was rampant. In other words, our racial caste system meant his choices—the roads on which he could walk through life—were profoundly limited, the racism of the state cherry-picking his options, some decent and some bad and some awful, since his birth. Indeed, his first brush was the state happened when he was only a little boy, and, without process or, according to his family, good reason, the state removed him from his home for a stint at Camarillo State Mental Hospital, an institution for adults. Or maybe since before his birth—the state had been pounding at his family for generations. His father, born into Jim Crow, was incarcerated for having a gun. His black great-grandmother was murdered by racist vigilantes. A generation or two before her, the family line is bludgeoned by chattel slavery in antebellum Alabama and Louisiana. We can call slavery the start of the state’s interference; we can call life after the Civil War the middle; we can call the state scrambling my dad and his sisters in and out of institutions the middle, too; and we can call how my dad died the end. Because I connect how he died to how the state inserted itself into his family and his life.

The continuity is haunting, and so very, very American. Alabama and Louisiana, where our tall, big-boned genes survived despite being treated like n*****s; a slurry of horrors though chattel slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow; my dad’s father in and out of prison; my dad in and out of foster care, institutions, and prisons; the effects of prison—what we’d now probably call post-traumatic stress disorder; my dad’s decision, both willing and forced, to live as he did, paying rent with his body; his landlords calling him, with a laugh, the Big Nig. My dad, who was joyful, brilliant, and gregarious, who loved John Coltrane and fresh tortillas and kids’ laughter, who spoke two languages and could fix anything, must have heard himself described in that reductive way, in some form or another, his whole life. Recently, I opened one of the storage crates we cleared out of his house to read his court papers. Trial transcripts, parole papers, letters to and from his family. In one transcript he is described, over and over, by every witness, as the large Negro man. They pointed to him at the defense table and said, “The large Negro man sitting over there.” Or described the guy with the gun, scooping jewelry from the case into a sack, as “a large Negro man, like him.” Arrested, tried, convicted, prison; the state, the state; he made choices that set the state in motion, but how many choices did he have?

When I became a lawyer, my dad cried and took my hands and said I was going to make people whole. What I wish I could tell him is that the wholeness I seek cannot be attained—not when the state hovers in the doorway, not when the state redacts decades and lifetimes, as if we never existed, or as if our existence were a mistake to be corrected. Instead of memories that can be shared and tilled like soil, made to bring forth new beauty and knowledge—seventeen years of memories in my dad’s case—we have the state, with its insatiable desire to redact and desecrate Black and brown lives. We have, instead of overflowing, voluminous, unabridged lives, an extraordinary erasure. That loss cannot be made whole.

Adapted from DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN: Essays on Race, Gender, and the Body by Savala Nolan. Copyright © 2021 by Savala Nolan. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com