A version of this article also appeared in the It’s Not Just You newsletter.Sign up here to receive a new edition every Sunday morning.

I’m a tech believer. My first job with TIME was to set up new communications systems and convince cranky foreign correspondents to trust them. Alexa and Google Home have colonized my apartment. And not only did I give my DNA to 23andMe, but I even answer their follow-up questions about whether I like olives or get carsick so they can map those genes. (Naturally, I also want to donate my body to research after I’m done with it–and if there were a way to send me a report in the afterlife about what they find, I’d request it.)

So you can imagine how very interested I was when Fitbit and other wearable health trackers, including Amazon’s Halo and the Apple Watch, started coming up with ways to show us data on our stress levels. There’s a bevy of new devices that monitor not just our heart rate, daily steps, and the quantity of our sleep, but the quality of our sleep by hour, skin temperature, and fluctuations in our blood oxygen saturation. Many of these biomarkers relate to our mental wellness and physical health, and there’s new wearable technology that picks up on our emotions.

But even data geeks like me realize there are crucial questions about whether technology is a solution or part of the problem when it comes to stress management. It’s fair to ask whether the very act of constantly checking personal health stats on our phones is antithetical to the kind of mindfulness and meditation practices that alleviate stress. And then there are all the sticky issues around data privacy.

So as annual global spending on wearable tech rises to more than $80 billion a year and rates of stress and anxiety skyrocket simultaneously, we wonder: Is a quantified self a happier self?

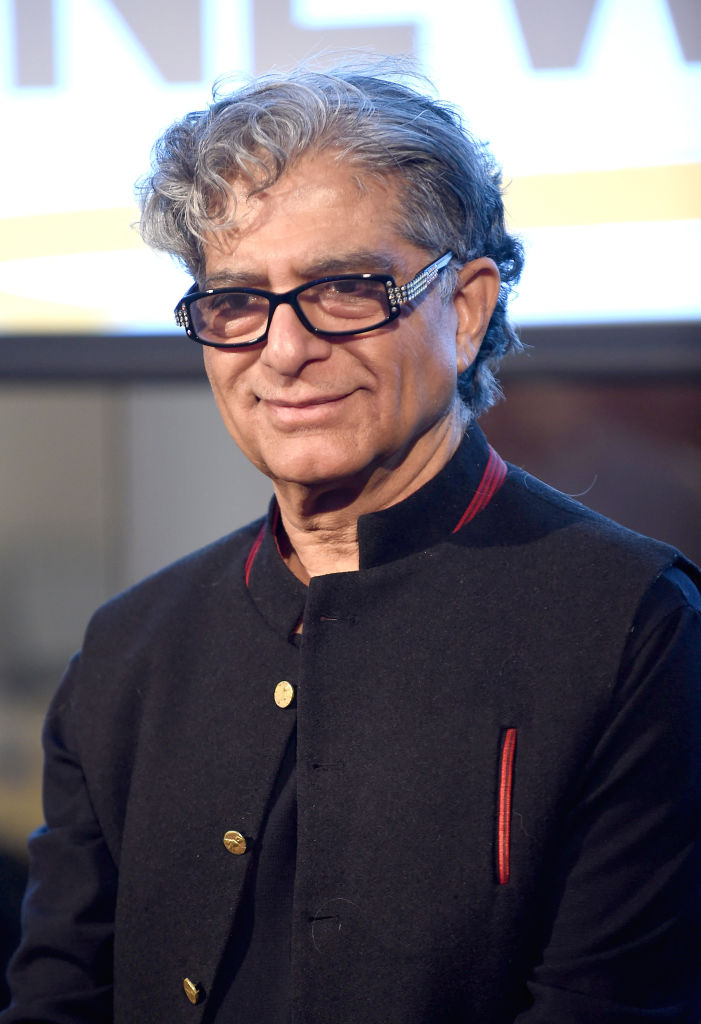

I spoke to mindfulness expert Deepak Chopra, M.D., and Fitbit CEO James Park about some of these questions. They’ve recently partnered on a series called “Mindful Method,” an expansion of Fitbit Premium‘s health tracking and content offerings. It includes short video meditations led by Dr. Chopra on cultivating the mind-body connection, getting better sleep, mental wellness, and my favorite, “resetting your bad mood.” This collection is paired with new Fitbit technology that detects electrodermal activity (EDA) responses–tiny electrical changes on your skin that can indicate a stress response.

Both Park and Chopra will tell you they see tech as a neutral actor, one that can be used to better lives or exploit societal weaknesses. Park uses the example of controversial algorithms that favored the sharing of extreme content on Facebook and other social platforms, which can lead to negative behavior. But Park sees positive opportunities in applications that provide ever-more customized health offerings: “What’s fascinating to me is that you can use these same tools to look at populations and try to nudge them in ways that actually result in really positive behavior.”

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Subscribe here to get a fresh edition every Sunday

And on the fundamental question of whether health tracking devices are an impediment to mindfulness or an facilitator, Chopra is unequivocally in the latter camp.

I think of technology as the evolution of human consciousness. Who created technology? We created technology, right? And technology is unstoppable. So how do we use it to our benefit? says Chopra.

To that end, more wearable health trackers like Fitbit are adding mental wellness features and content. For example, these devices can help you become more aware of your emotional fluctuations by asking you to log your moods and showing you data about related wellbeing biometrics (like the quality of your sleep, your physical activity, heart rate, or some of the newer wearable capabilities that can recognize stress reactions in your voice or skin).

There isn’t much independent research on whether digitally logging your moods is effective in managing your mental health. Still, the concept is similar to longstanding suggestions that it can be beneficial to keep a mood journal manually to identify your emotional patterns and triggers.

However, according to some studies, monitoring one’s biometrics can leave some users feeling both empowered and anxious. You could say our smartwatch relationships are complicated. Not only do we share intimate information with them, our weight, what we eat, how we feel, but they now give us biometrics that only elite athletes once had. These are things we didn’t know we had to worry about like whether we’ve enough REM sleep or our heart rate variability. That amount of information can be overwhelming, and dispiriting if you’re not meeting your goals. And on the flip side, some people become anxious when they don’t have access to their health trackers.

In a lot of ways, our gamified brains are primed to respond to trackers’ immediate feedback. Follow a guided breathing exercise and see your heart rate drop–it’s satisfying.

“Today, we are not even talking about bio-feedback; we’re talking about bio-regulation, which means real-time data, real-time feedback, and real-time intervention,” says Chopra. “But,” he adds, “it’s a mistake to think that the quantified self is not the qualitative self as well. The quantitative self is data that makes you feel better about yourself without feeling guilty.”

If you’re like me, this kind of data revolution isn’t so alarming, but there are obvious sensitivities about all the personal health information in the hands of private companies. This issue particularly current for Fitbit, which was acquired by Google earlier this year. Park assures us that Fitbit’s data will not be used by Google for ad targeting, explaining the terms of the deal this way: “The regulators have said, ‘Hey look, you can’t just make a verbal commitment, it actually has to be enshrined and encoded in the technology itself, and in the systems that enforce the separation.'”

How data is gathered and used is undoubtedly one of the most vexing questions of our time. But Chopra believes it is medicine’s most valuable tool in managing chronic health conditions. He is working on a separate project for which a thousand people have agreed to share their biometric and other personal data from cradle to grave. “Data can give you instant knowledge of how to manage somebody’s concerns, whether they’re mental, emotional, physical, or even spiritual,” he says.

Read more: My Fitbit Is More Interested In Me Than I Am

Even those who have avoided the quantified-self movement would likely agree that we need more and better mental wellness interventions. There’s evidence the pandemic worsened what was already a stress epidemic. The American Psychological Association recently reported that 84% of U.S. adults reported feeling at least one emotion associated with prolonged stress in the prior two weeks. And, as Chopra and other health experts point out, long-term stress has all kinds of cascading physical health consequences, which can include high blood pressure, obesity, depression, and more.

At the very least, the debate over whether tech helps with mental wellness is bringing more awareness of the tremendous toll of rampant stress and burnout. And this conversation goes beyond changing our individual lifestyles and behaviors. It’s also about transforming institutions and workplace culture to get at some of the systemic causes of stress. And in that fight, data is an ally.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Subscribe here to get a fresh edition every Sunday.

As always, you can send comments to me at: Susanna@Time.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com