A TikTok accusing Converse of stealing designs that were submitted by an intern applicant has shed more light on alleged copying in the fashion world and the few avenues available to designers who suspect their art has been co-opted by brands.

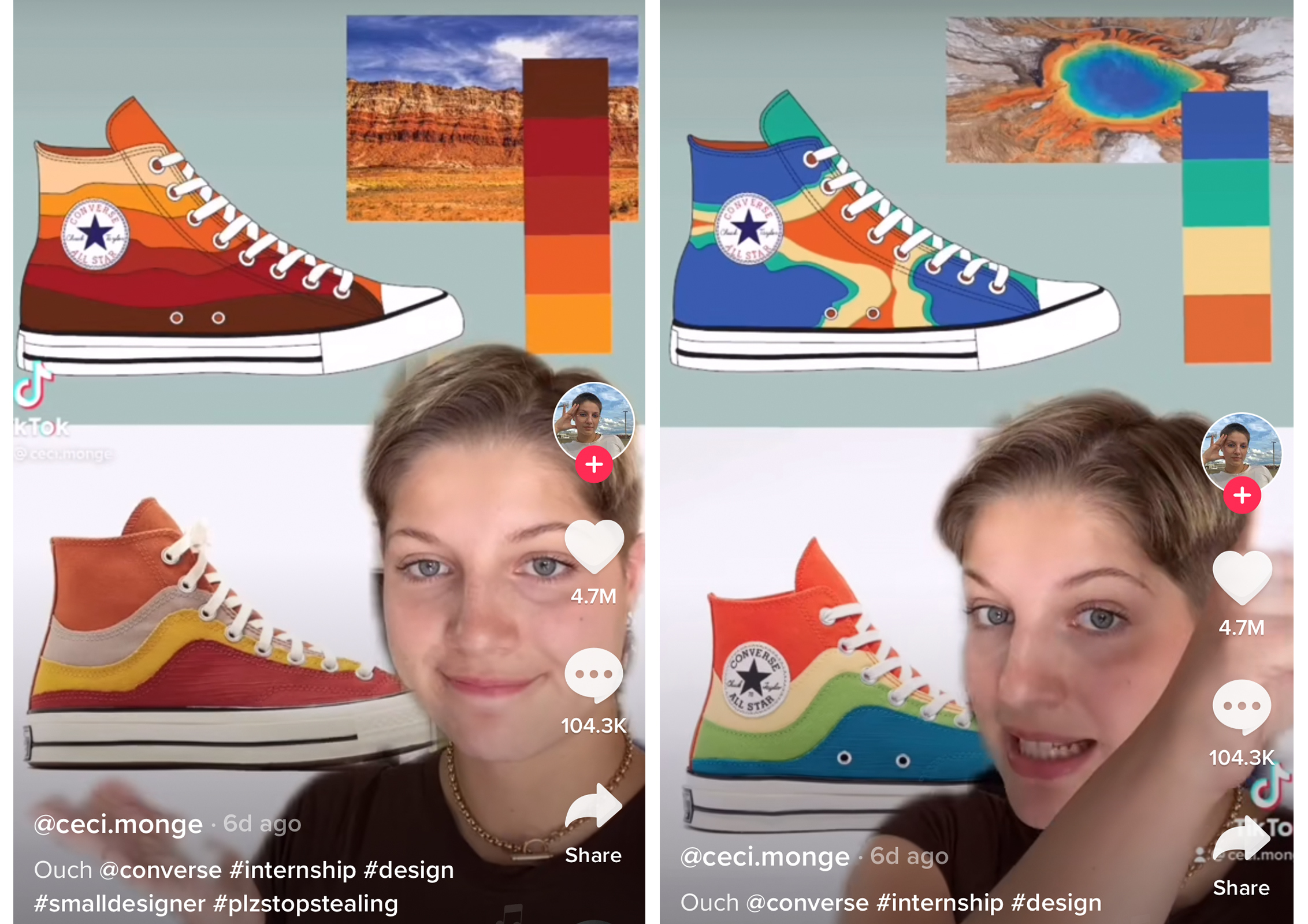

In a now-viral video posted on May 21, 22-year-old designer Cecilia Monge juxtaposed designs she says she shared with Converse in November 2019 with both the Bright Poppy and Red Bark editions of the company’s Chuck 70 National Parks high-tops. In the video, Monge states that the shoes and her designs are “essentially the same.”

“I originally saw Converse’s National Park line while I was just scrolling through TikTok, and my immediate reaction was, ‘Wow, that looks really similar to what I pitched two years ago.’ So I ran downstairs, checked my files, looked at the PDF that I had sent in, and started panicking a little bit,” Monge tells TIME. “Within the [design] industry, you learn that this is something that happens to smaller designers and, unfortunately, is super common. So I made the TikTok because I wanted to share my experience and spread awareness.”

Monge’s original TikTok has since garnered over 17 million views and 5 million likes and has also spread to other popular social media platforms. On May 23, it was picked up by Instagram fashion watchdog Diet Prada, with the account saying “Converse’s shoes appear uncannily similar to Monge’s designs, which feature organic waves of gradated color inspired by national parks. One of Converse’s color [waves] even mirrors the same hues and color order of the designer’s Yellowstone-inspired shoe.”

In a statement obtained by TIME, Converse denied that the designs were based on Monge’s portfolio submission. “As a matter of standard legal policy, we do not share unsolicited portfolios of job applicants across the business,” a spokesperson told TIME. “This concept and design was completed before we received an application from the candidate.”

The company further elaborated on its “footwear development process” in an email to Monge that she shared with TIME.

“In November 2018, our design team was working against a seasonal Nor’easter creative direction, and the shoe design was initiated in April of 2019,” a spokesperson for Converse told her. “The first results of that Chuck 70 design [were] released in October 2020, which took inspiration from the map patterns of Nor’easter storms. Due to the popularity of the style, we continued it in 2021 under our design concept ‘Hybrid World,’ which explores original design concepts informed by the physical and digital realities of modern lives. The Great Outdoors and specifically, the appeal of National Parks served as inspiration for various color palettes.”

Coincidental or not, the controversy sparked by Monge’s video illustrates how complicated and difficult it can be to legally protect fashion design, according to Susan Scafidi, the founder and director of Fordham’s Fashion Law Institute.

Scafidi says American copyright law protects only the two-dimensional aspects of fashion design—like the pattern of a fabric—and not the functional aspects—like the cut of a fabric—and that designers often have to turn to patent law to protect the decorative elements of functional items. But obtaining a patent can present some challenges.

“Over 100 years ago, the United States Copyright Office decided that all fashion, no matter how fanciful, is functional. So copyright doesn’t protect it, which, in theory, means designers could go to the Patent Office to protect their designs,” Scafidi says. “But the Patent Office standards for what qualifies as new are pretty high. In the case of copyright, you can protect anything that’s original. In the case of patent, it has to be new to all the world. And even if you meet that standard, it’s expensive and time consuming. For the average design that will be around for a season and then gone, it’s just not worth it.”

And if a designer does decide to pursue legal action against a large corporation, attorney Nicole Haff, a litigation partner at Romano Law with a focus in business and intellectual property, says they’re often met with intimidating resistance.

“The biggest hurdle is you have an independent designer suing a big company. It’s a David and Goliath situation,” Haff says. “If you threaten to sue, you often get a very heavy-handed response because they know a lot of these artists are [smaller] artists. And these companies have a lot of money and a lot of resources. They have their own legal departments. It’s a very difficult battle.”

In Monge’s case, Scafidi says that while she might be able to get a copyright on her design if she chose to file a claim, the legal process would likely take years.

“Assuming the Copyright Office looked at the designs she created for those shoes and said, ‘Yes, those are distinct enough to be copyrighted,’ she’d still have to file her case in court,” Scafidi says. “That means time and money. So maybe five years from now, she’d win. But it’s so much quicker to make that TikTok video.”

Some designers and artists still choose to take their cases to court. In 2015, Brooklyn-based street artist Joseph Tierney, better known as Rime, brought a lawsuit against Moschino and creative director Jeremy Scott alleging that the brand used imagery from one of his murals for a dress worn on the runway by Gigi Hadid and to the Met Gala by Katy Perry.

“If this literal misappropriation were not bad enough, Moschino and Jeremy Scott did their own painting over that of the artist — superimposing the Moschino and Jeremy Scott brand names in spray-paint style as if part of the original work,” the complaint stated. Rime and Scott eventually settled following a nearly yearlong dispute.

The obstacles associated with legally protecting design have also led to an increase in designers opting to call out companies on social media, Scafidi says. One recent example of this trend occurred last summer when designer Tra My Nguyen took to Instagram to accuse Balenciaga of appropriating her work.

A similar instance took place in 2018 when Carrie Anne Roberts, the British designer behind the clothing brand Mère Soeur, accused Old Navy on Instagram of allegedly stealing the design of one of her graphic T-shirts. “When you’re having a hard week/month then you find out [that Old Navy is] the next in a long line of big brands to rip you off except they literally lifted the EXACT SAME DESIGN from your shirt,” Roberts wrote.

Following some public outcry, Old Navy ultimately pulled the shirt from its site.

“Over the past five years in particular, many designers are simply eschewing law and trying their cases in the court of public opinion on social media,” Scafidi says. “But using social media as a tool can be a double-edged sword. Sometimes people pile on and say, ‘Actually, we don’t think this is copied.'”

So far at least, it seems the opposite has largely been true for Monge.

“A common thing people were telling me online was, ‘That’s what you get for sharing your work.’ But in the design world, no one’s going to hire you if they don’t see what kind of work you do,” she says. “So the most gratifying part of this whole thing has been that other designers have reached out to give me tips and advice on how to prevent this from happening in the future and to thank me for speaking up. That’s made me feel better because my goal with the video was to get people to talk about their own experiences so that smaller designers feel less alone.”

Given that Monge’s designs may not be protectable from a legal standpoint, Haff says that the nature of the fashion industry puts her in a really tough spot. While smaller designers like Monge typically have to share their designs to get noticed, sharing them may also increase the likelihood that they’ll be used without the designer’s permission.

“She essentially gave away her ideas for free,” Haff says. “Not doing that is easier said than done because the job market is so competitive now and everybody is basically providing a lot of free work on applications. But they’re doing so at their own peril.”

In a follow-up TikTok posted on May 25, Monge said that while Converse did reach out to her over email, the company “hasn’t apologized or compensated me or credited me in any way.” She went on to encourage other designers to use the hashtag #designersspeakup to talk about their experiences.

For her part, Monge says that to bring about change in the industry, she thinks transforming the culture of fast fashion is necessary.

“A lot of larger companies are built in a way where they don’t really value the more artistic side of things,” she says. “And a lot of fast fashion retailers churn out so many clothing and shoe designs throughout the year that their design process, from conception to production, is so quick they sometimes scramble for ideas. So the issue is changing that culture and prioritizing people’s minds and talents and creativity instead of treating design like just another gear that has to turn to get product out.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Megan McCluskey at megan.mccluskey@time.com