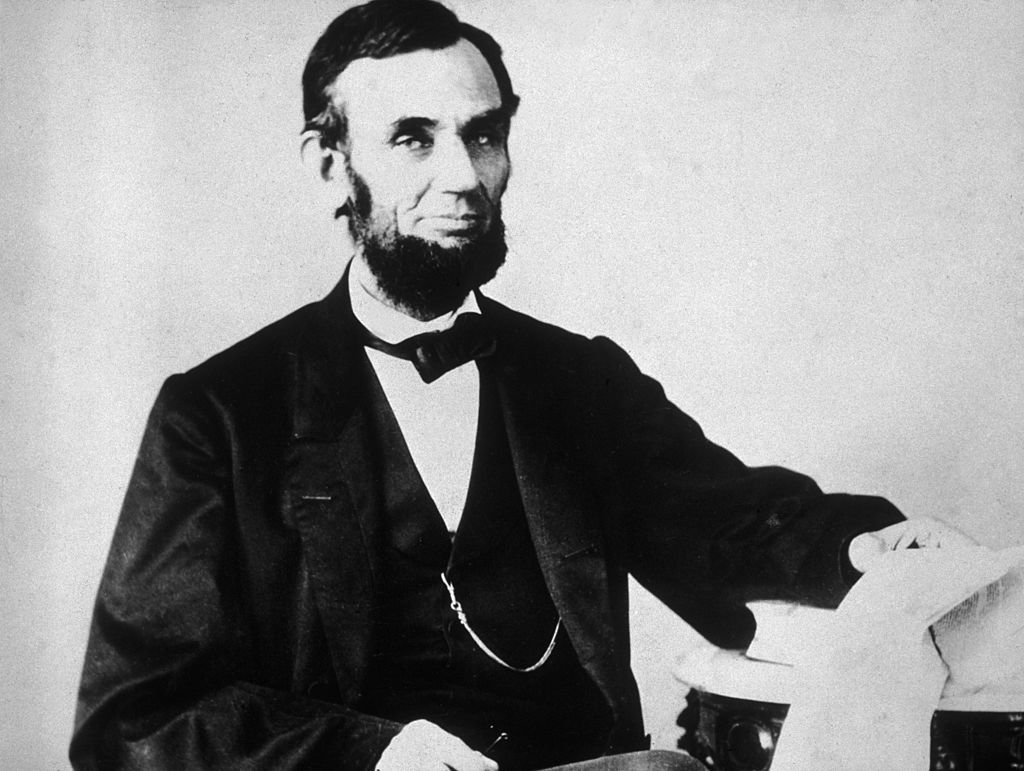

Abraham Lincoln is one of those individuals whose stature is so large that he has become engulfed in myth—myth that often replaces reality. In poll after poll, the man who died on April 15, 1865, has consistently been ranked by historians and the American people as our greatest president. Both political parties claim to represent his values and never hesitate to invoke his name to bolster their image. Over 145 statues of Lincoln stand, more than two dozen of them in foreign countries. Lincoln is recognized internationally as a symbol of freedom and all that America stands for.

Yet now, he finds himself a target of those who would pull down those statues. He has evolved from being called the Great Emancipator to “a stone-cold racist.” His domestic life has been likewise dissected. Some claim he hated his father, found himself in a marriage made in hell, suffered from Marfan Syndrome, Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia, even syphilis. Had John Wilkes Booth not assassinated Lincoln, some assert, he would have died in office during his second term from one or all of those diseases.

Scholars are not the only ones reevaluating Lincoln. In 2016, as a result of a misstatement by a candidate running for state office, students at the University of Wisconsin demanded that his statue be removed from its place of honor in front of Bascom Hall because “he once owned slaves.” Even after that was proven false, they called for the statue’s removal because he had ordered the murder of 38 Dakota Sioux Native Americans. Similarly, in January 2021, Lincoln was among the historical figures whom the San Francisco school board voted to remove from the names of 44 schools, because, as one board member stated, “He contributed to the pain and decimation” of the Dakota Sioux. (The renaming process was suspended this month.)

Historical revision in itself is not bad, but it must be based on facts. Truth, after all, is the stock-in-trade of all historians. Lincoln said it best: “History is not history unless it is the truth.”

But getting to the truth is seldom easy. In the case of Lincoln, this is particularly true. One can find documentation of an unending number of people who were eager to give personal testimony to their relationship and knowledge of the great man. Many exaggerated, a few lied. For example, 11 people swore they were in the state box at Ford’s theater the night he was shot. Twenty-six people claim they carried him from the theater to the Petersen House where he died. Fifty-six people claim they were standing at his bedside, witness to the moment of his death. Four individuals, all honorable men, claimed to have placed coins on the deceased Lincoln’s eyes.

When it comes to his pre-presidential years, the truth is even harder to assess. Documentary records are scarce, so historians turn to personal recollections by people who knew Lincoln, some better than others—people Lincoln historian James G. Randall referred to as having “dim and misty” memories.

So how are we to judge the truth about the man?

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Lincoln was our most eloquent president. Still, it is his actions by which he should be judged. The Gettysburg Address, his farewell speech to the people of Springfield, his condolence letter to Mrs. Bixby, and his Second Inaugural address are considered among the greatest writings in western literature. Yet the Emancipation Proclamation, which reads like a bland legal document, contains the most important words that ever flowed from Lincoln’s pen: “All persons held as slaves within any state or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Modern-day critics rightly point out that these words freed very few slaves at the time of their issuance in 1863. However, just as the Declaration of Independence did not free a single American, the Emancipation Proclamation established the basis upon which a war would be fought and freedom won.

All historical figures led nuanced lives, and those gray areas are important to acknowledge. Lincoln never owned slaves, but there are ambiguities in his personal views on race. And it is true that he approved the death sentences of 38 Native Americans, though he did so after he reviewed the trial records of 303 Dakota Sioux who had been condemned to death after the 1862 Sioux Uprising in Minnesota. In the end, he overturned the convictions and sentences of 265 and allowed 38 sentences to stand.

But when it comes to the reason why Lincoln deserves his place at the top of all those rankings, the answer is relatively simple. Abraham Lincoln might not have loved his father, might have had a difficult marriage and might have suffered several life-threatening diseases, but there is no solid evidence to support such claims. What we do know for certain is that he saved the Union and, in doing so, helped bring about the freedom of millions of enslaved people. Judge him by those actions, and there will be little room for doubt.

Edward Steers Jr. is the author of Getting Right With Lincoln: Correcting Misconceptions About Our Greatest President, available from the University Press of Kentucky.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com