Netflix’s latest true crime documentary series, Murder Among the Mormons, chronicles the strange events surrounding a trio of bombings that rocked Salt Lake City, and especially the Mormon community, in October 1985. It’s a complex story that, despite making national news at the time, has remained widely unknown over the past 35 years.

According to series creators Jared Hess (Napoleon Dynamite) and Tyler Measom (An Honest Liar)—who were both raised in the Mormon faith—that’s likely because the issues at the heart of the story were mostly of regional concern. “It was Utah, it was Salt Lake City, and it remained very isolated,” Hess says. “There’s been books written about it, so the material’s been out there. But most people just don’t know about it.”

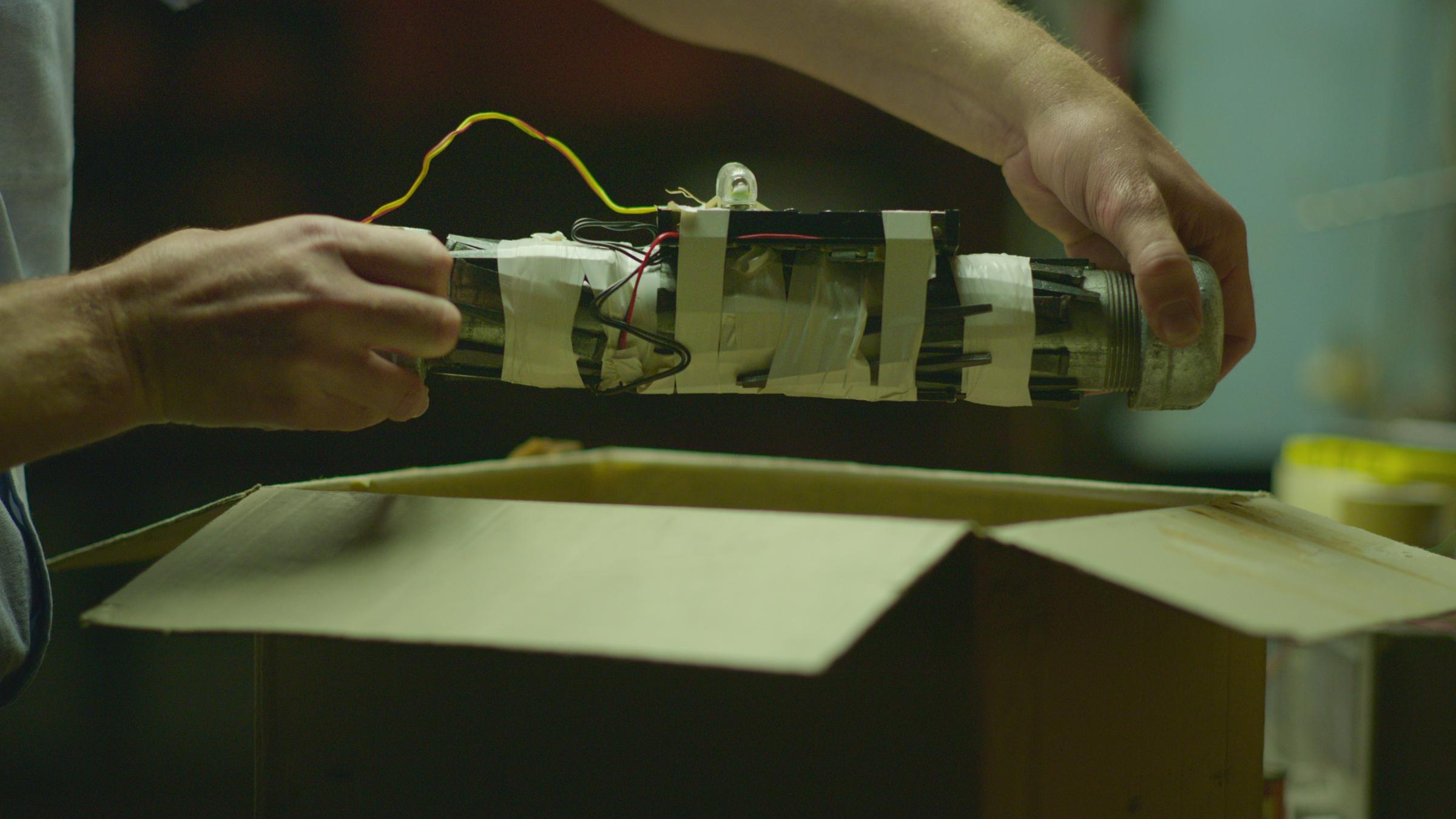

At the center of the three-part docuseries is Mark Hofmann, a master forger who was convicted in January 1987 of killing stockbroker Steven Christensen, a Mormon bishop and document collector, and Kathleen Sheets, the wife of Christensen’s former business associate Gary Sheets, with pipe bombs in an attempt to prevent the discovery of his fabrications. Hofmann, then 30, became a suspect in the case when he was seriously injured by a third bomb that exploded in his car the day after the first two bombings.

“Because it’s a regional story, I think that people who come into the series cold are shocked at how prolific Mark Hofmann was and that he was the greatest forger of all time,” Hess says.

“The beauty of that was that it allowed us to craft a narrative to kind of keep that secret,” Measom adds. “We weren’t retelling something that everyone knows. So we were able to suspend this whodunit for an episode and a half, and then in episode three reveal how and why he did it as opposed to who did it.”

Murder Among the Mormons, in the vein of previous Netflix offerings like Wild, Wild Country, relies on a mix of archival footage, home videos, dramatic reenactments and interviews with subjects connected either to Hofmann personally or to the case as a whole to reconstruct the events surrounding the bombings.

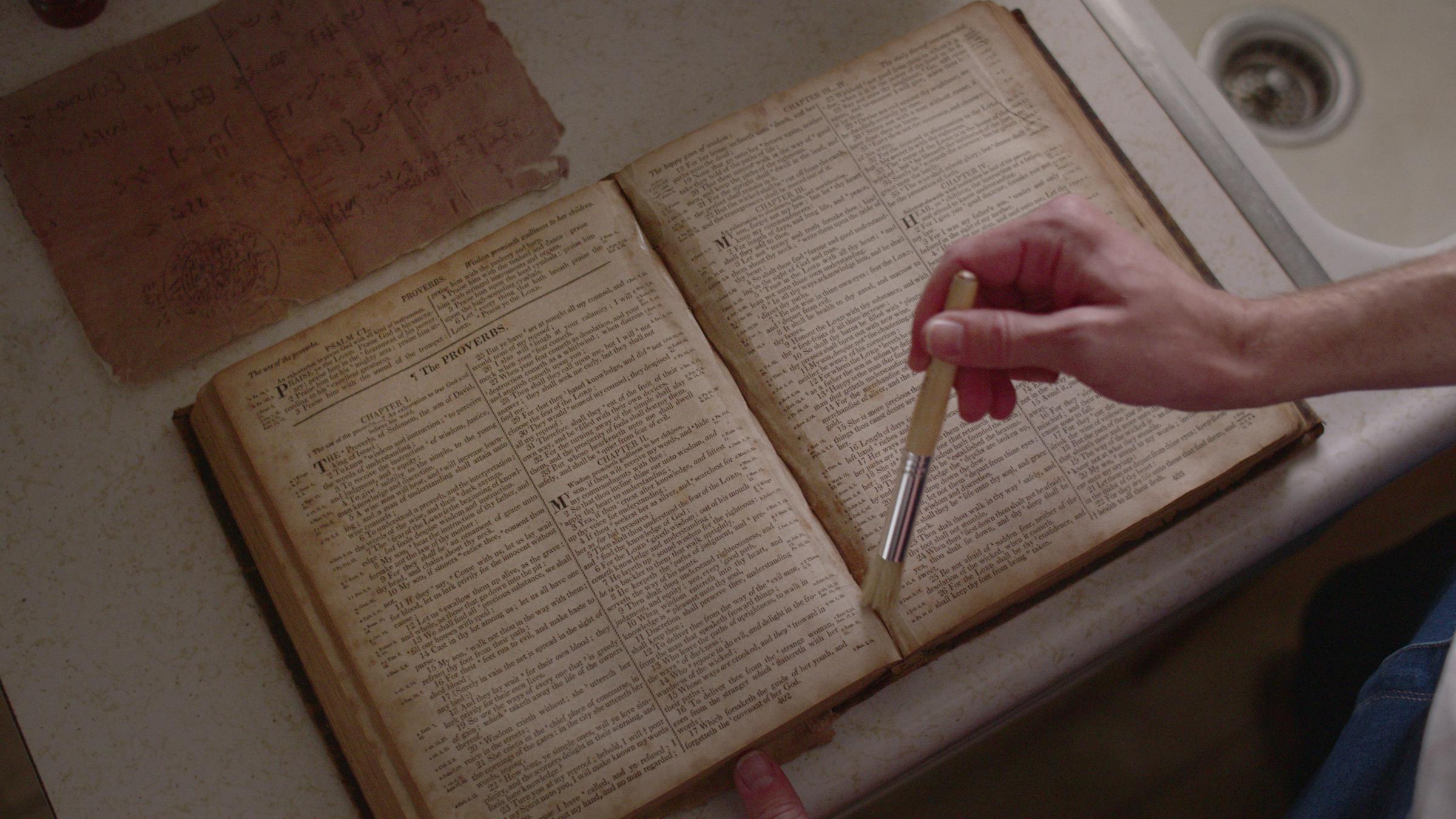

Leading up to the violence of Oct. 15, 1985, Hofmann had spent years forging and dealing a variety of historical documents, including several purported to have been written by early members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (widely known as the LDS or Mormon Church). Two of Hofmann’s forgeries in particular, the so-called Salamander Letter and McLellin Collection, threatened to shake the foundations of the church by undermining some of its most important teachings. An unknown number of Hofmann’s forgeries may still be in circulation today.

Even though the series explores a dark period of time for the LDS Church, Hess says that the Mormon community’s response has been positive thus far.

“Hearing the details and having a context for what really happened is really liberating and empowering. For people to be able to confront their fears over the mythology of this whole story is a great thing,” he says. “And I think for the church at large, as an institution, there aren’t any surprises. They know what happened, and ultimately, the bad guy goes to jail. They were victims, just like many other institutions that we feature. The FBI was duped by Mark Hofmann. Sotheby’s, universities, historical institutions—all kinds of people from all walks of life.”

Following an extended investigation into Hofmann’s criminal activities, he pled guilty to two counts of second-degree murder and two of theft by deception in a plea bargain that allowed him to escape a possible death penalty. He was sentenced to five years to life, with the judge recommending that he never be released. At a 1988 parole hearing, the Utah Board of Pardons ordered him held for his “natural life” in prison, citing a “callous disregard for human life.”

Hofmann was held under maximum security at the Utah State Prison in Draper until December 2015, when he was transferred to the Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison. He remains housed there today.

Despite writing numerous letters to Hofmann throughout the years-long process of making Murder Among the Mormons, Hess and Measom say they never received a response from him. But if they’d had the opportunity to communicate with him, Measom says he would have liked to learn more about what drove Hofmann to a life of crime.

“Mark has kept his secrets to himself. I think that’s all he has, frankly. He’s sitting in jail with very little chance of ever getting out. So the one thing he has is the power to wield his story,” he says. “I’d like to understand what caused him to use his powers for evil, as opposed to good. Was there ever a time when he thought, maybe I can work for the FBI and be a document examiner, instead of a document forger? That crux, or that fork in the road, is always interesting, especially in filmmaking: why someone becomes a superhero versus a supervillain.”

Ultimately, if there’s one thing Hess and Measom hope that viewers take away from Murder Among the Mormons, it’s that the broader themes of the story are still relevant today—especially in the context of our current political climate.

“We live in a world of misinformation. And a lot of the material that Hofmann was producing [evoked] a very visceral, emotional response—especially as it related to church documents, where you had a history that everybody believed to be true about the origins of the church,” Hess says. “In this day and age, we have to be so careful about the narratives that we choose to believe and we have to dig a little deeper and not just accept them on an emotional level because it feels right. Otherwise we can really be led down a path that will end in tragedy.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Megan McCluskey at megan.mccluskey@time.com