Jessica Salas stood up from her plush velvet seat in Milwaukee’s Pabst Theater on Tuesday night, her second-grade daughter Layla in tow, and carefully read her question for President Joe Biden from a white sheet of paper. “My children,” she told Biden, “often ask if they will catch COVID, and if they do, will they die. They are watching as others get the vaccine, and they would like to know – when will kids be able to get the vaccine?”

Biden, who joked at the beginning of the town hall that he preferred kids to people, immediately turned his attention to Layla, assuring her that it was unusual for children to contract the coronavirus but that he understood her fear. “When things change, people get really worried and scared. But don’t be scared, honey,” Biden said. “You’re going to be fine. And we’re going to make sure Mommy is fine, too.”

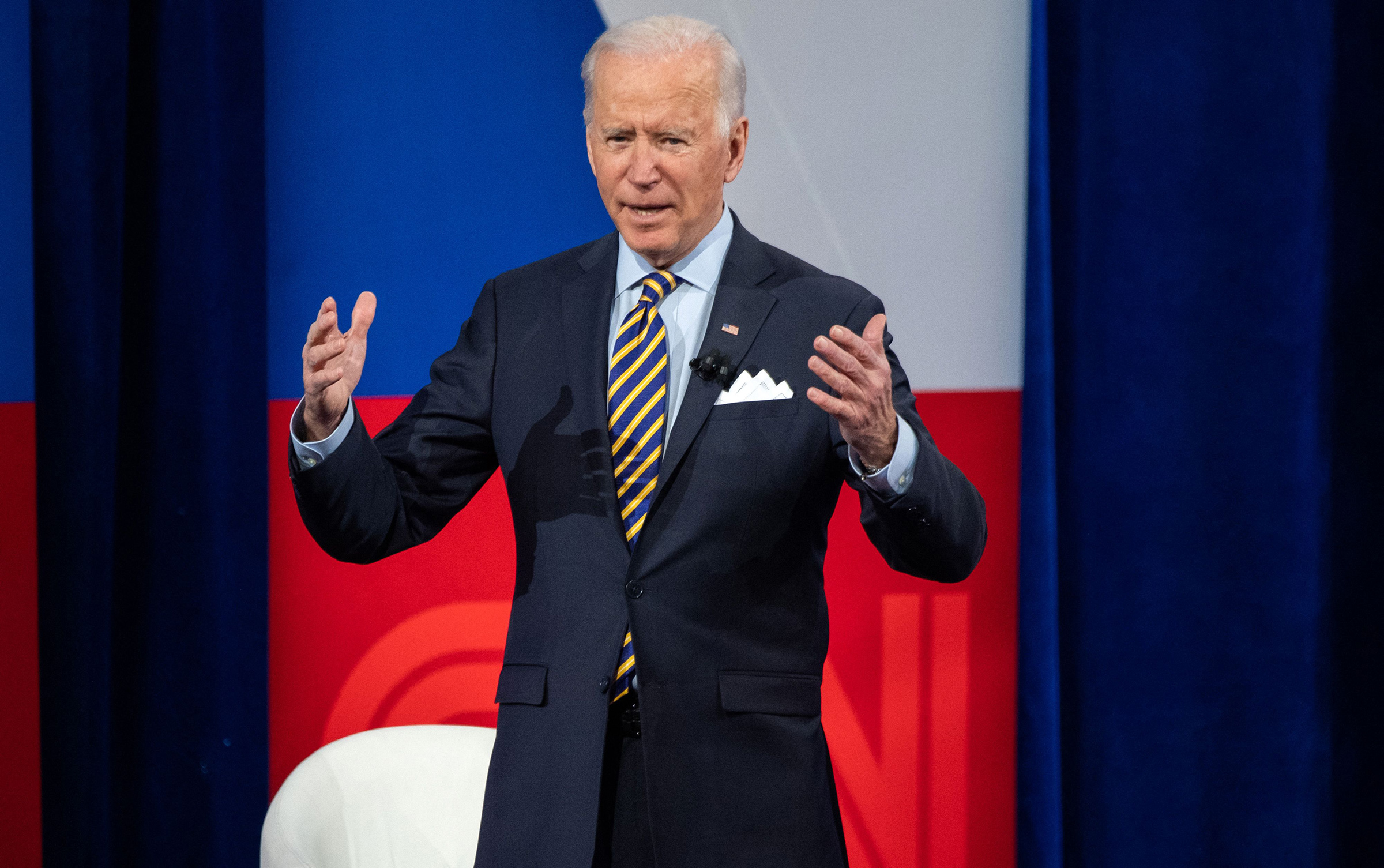

This exchange during the President’s first town hall was classic Biden. In his half century in political life, Biden has always prided himself on his ability to connect with Americans, and he’s doing it again now as he gets out of Washington to pitch his $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package to voters in key swing states. Stepping out of the shadow of former President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial, he is reclaiming the spotlight with the first two major domestic trips of his tenure. In addition to Tuesday’s town hall in Wisconsin, he plans to spend Friday in Kalamazoo, Michigan, touring a Pfizer vaccine production facility and meeting with workers. (The White House postponed Biden’s arrival in Michigan by a day because of bad weather in Washington.)

For Biden, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The package is not only the first big legislative item on his presidential agenda, but aims to launch a recovery from the pandemic and economic crisis that will inevitably define his first term. The trips also reveal a longer-term strategy, advisers and strategists say. Presidential travel during the pandemic takes on greater meaning when large parts of the country have effectively been in lockdown for a year and public safety guidelines must be strictly adhered to. In selecting two of the most critical battleground states, he’s using his political capital to tell the voters that helped send him to the White House how he’s delivering on his campaign pledges — and why they should stick with Democrats in elections to come.

“It’s no accident that Wisconsin and Michigan are the first two trips for Biden,” says Jim Margolis, a Democratic strategist. “They were must-win states in 2020, have big elections in 2022 and will undoubtedly be in the electoral bullseye again in 2024.”

But first and foremost, Biden is hoping to cement bipartisan support for his relief bill. Biden’s campaign message was predicated on the idea of unity; he pledged to restore civility to Washington by reaching across the aisle and breaking through the intractable polarization that dominated his predecessor’s tenure. So far, no Republican lawmakers have said they are on board with this package, instead expressing sticker shock. But polls show the package is exceedingly popular among Americans: a Feb. 3 Quinnipiac poll found 68% of Americans currently support the package, including 37% of Republicans, and that 78% back another round of $1,400 stimulus checks.

Now the administration is using bipartisanship as a reference to the American people, rather than lawmakers, wielding this data to insinuate that if Republicans don’t ultimately get on board and back this package, it will be at their own political peril. “If you look at the polls, they are very consistent. The vast majority of the American people like what they see in this package and it should be noted by members of Congress as they consider whether they’re going to vote for it or not,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said on Tuesday.

The Biden Administration is trying to build on that support. Leading into this week, Biden and his staff have harnessed the technological skills they built during the campaign to pitch his COVID-19 package, relying heavily on socially-distanced meetings with advocacy groups and business leaders. Since Jan. 27, senior administration officials and other surrogates have conducted over 70 television interviews with local outlets in over a dozen states to discuss the proposal, including Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

But they also know that there is little substitute for the visibility that accompanies an on-the-ground Presidential visit. Margolis noted that making trips to two battleground states puts Congressional Republicans “on notice” that the Biden Administration is prepared to go around Congress and make the case for Biden’s large relief proposal directly to the public. The message for Republicans: “Think twice before you vote no,” Margolis says.

The White House has publicly downplayed the political significance of these destinations, aside from noting that, as politically divided states, constituents have a wide range of views that will prove fodder for debate. Wisconsin “was a state where people have been impacted by the pandemic, they’ve been impacted by the economic downturn and the President felt he could have a good conversation with people about the path forward, even people who disagree with him,” Psaki said Tuesday. “It’s not more complicated than that.”

While it’s true that both Michigan and Wisconsin have been hit hard by the pandemic and economic crisis, it’s equally true that Biden’s path to the White House ran through them. Wisconsin Senator Ron Johnson, a close Trump ally, is up for re-election next year, and Democrats are determined to oust him. And now that Biden has narrowly shifted both back to the Democratic column—he won Wisconsin by a mere 20,000 votes—he and his administration are determined to show these voters they don’t just matter every four years, and that he is providing them with the economic and pandemic relief he promised.

“One of the things we found out in the campaign was people just wanted stuff done,” says John Anzalone, Biden’s campaign pollster and longtime adviser. “This is about having a plan and executing a plan quickly.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alana Abramson at Alana.Abramson@time.com