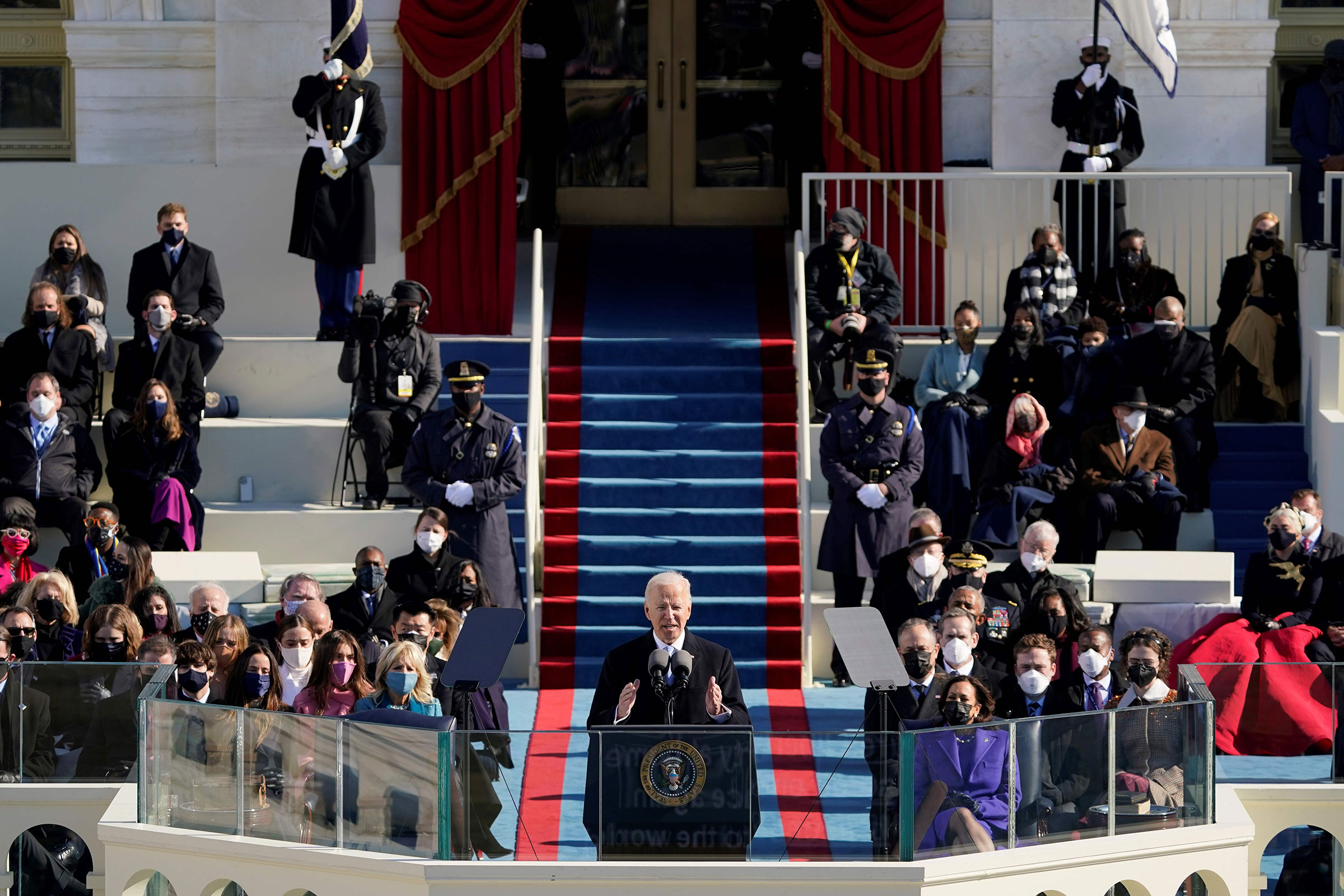

With a couple swipes of the pen within hours after taking office, President Joe Biden put the U.S. on track to return to its pre-Trump position on climate change. Biden rescinded the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline, directed agencies to seek to undo Trump’s rollbacks of many environmental regulations and recommitted the U.S. to the Paris Agreement.

But Biden would be the first to admit that restoring the Obama years’ state of play on climate in the U.S. is not enough. On the campaign trail, then-candidate Joe Biden listed tackling climate change as a top priority and promised to incorporate the issue into policy making across his administration. Now, with Biden in control of the executive branch and Democratic control in both houses of Congress, a new realization is starting to emerge: the Biden Administration may actually be in a position to fulfill some of its loftiest climate goals.

“We are now thinking in very ambitious terms,” said Representative Kathy Castor, a Florida Democrat who heads the House of Representatives committee charged with developing climate policy recommendations, on a Jan. 13 call with environmental groups. “We just have to shoot for the stars.”

The most immediate place to expect the Biden Administration to pursue ambitious action is in coming legislation to fund an economic recovery in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. On the campaign trail, Biden, like many of the Democratic candidates, proposed trillions of dollars in spending to fund U.S. efforts to combat climate change while also creating millions of new jobs. The economic fallout from COVID-19 has made federal investment of that scale to combat climate change more politically viable than at any point in U.S. history.

In recent weeks, Biden has doubled down on those promises. He stated plainly in an address to the nation on Jan. 14 that after funding direct measures to curb the pandemic, such as vaccines and testing, his recovery efforts would include “confronting the climate crisis with American jobs and ingenuity.” That same week, Brian Deese, his top economic advisor, told a virtual forum that Biden’s economic recovery strategy “puts solving the climate crisis at the center of creating jobs.”

The precise details of what Biden’s plan for the U.S. will include remain to be seen, but his allies expect the spending to include a focus on infrastructure improvements that will reduce emissions. The transportation sector, which now generates more emissions than other sectors like electricity production and agriculture, will likely be a key target with funding for measures like electric vehicle charging stations and reviving public transit. The price tag on these proposals is expected to dwarf the $90 billion dedicated to promoting clean energy in the 2009 stimulus package that Biden oversaw, which the Obama Administration billed at the time as the nation’s largest single investment in clean energy.

Spending hundreds of billions of dollars on clean energy in a COVID-19 stimulus plan may sound like an uphill battle given that many measures that respond directly to the pandemic have drawn opposition from conservative lawmakers. But, while skepticism from some on Capitol Hill is inevitable, many climate policy experts say the outlook for clean energy funding isn’t as bad as it may seem. Support for clean energy in the U.S. is high across the partisan and geographical lines that often divide American politics. And a growing percentage of Americans — particularly young people of all political stripes — say they are concerned about climate change. That broad support has translated to bipartisan support for some recent clean energy spending measures already. In December, Congress approved some $35 billion in spending on clean energy measures as part of its $900 billion COVID-19 relief package with relatively little controversy or opposition.

Democrats’ gaining control of the Senate will make a big difference, too. Wins in two Senate runoffs in Georgia created a 50-50 split in the upper chamber, effectively giving Democrats control as Vice President Kamala Harris will cast the tie-breaking vote in split decisions. Most legislation still needs 60 votes to win approval in the Senate, but Democrats could turn to a process known as budget reconciliation, which only requires a simple majority to pass spending measures including climate stimulus funding. Perhaps just as important, Democrats will now control what gets considered on the Senate floor. “There are things that may be possible to do even without bipartisan cooperation,” says Jason Bordoff, who advised the Obama Administration on energy policy and now heads the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

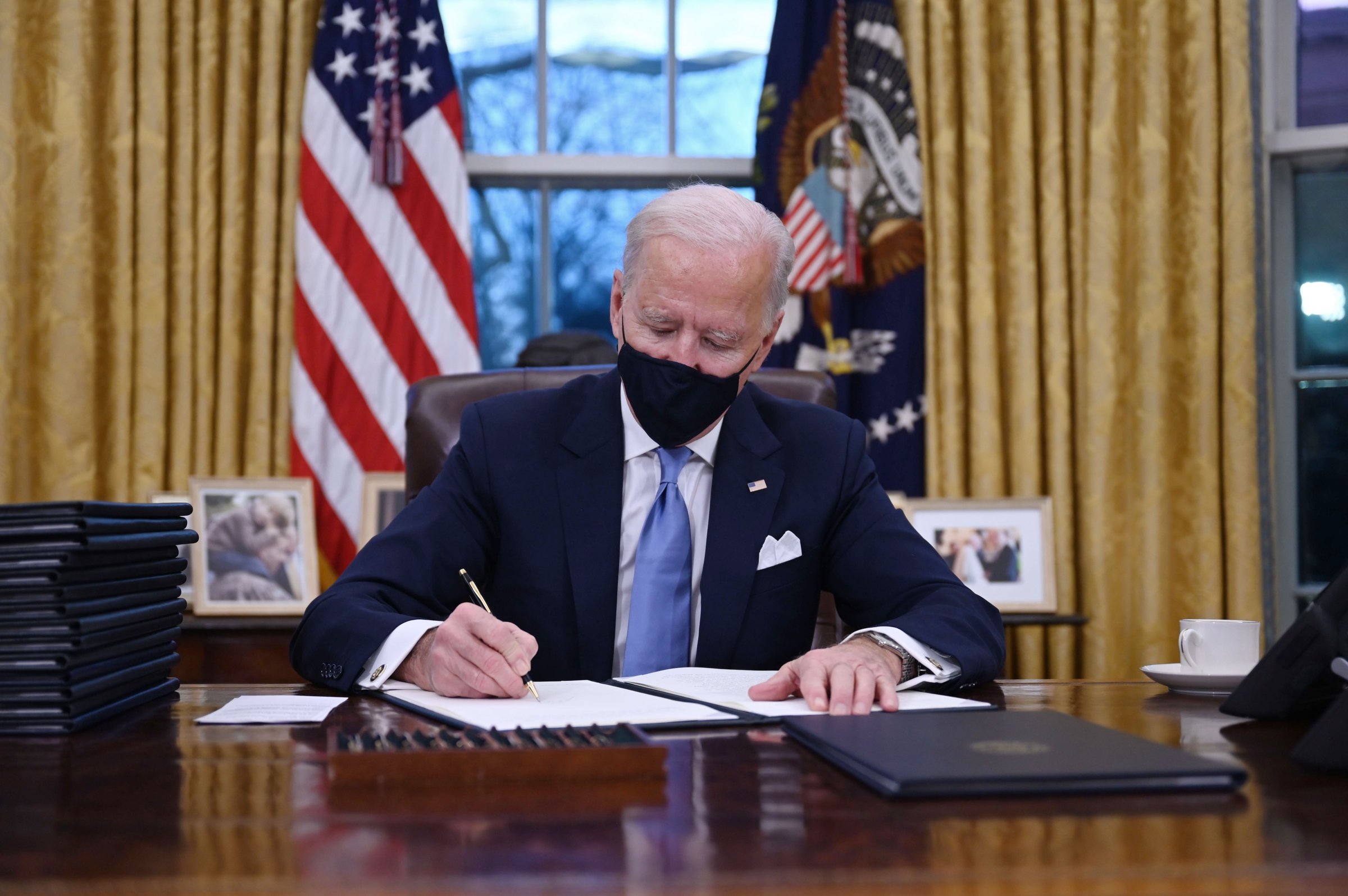

The Biden Administration is expected to pair the push for climate-related spending with an aggressive effort to incorporate climate change across policy making. Biden took the first steps to enacting this strategy — which climate policy experts call a “whole of government approach” — when he stepped into the Oval Office Wednesday and signed executive orders directing government agencies to seek to restore Obama-era environmental regulations that were undone under Trump.

Some of that work has already begun. Last year, after Biden’s victory was clear but it still seemed unlikely Democrats gain Senate control, the incoming Biden team started positioning itself to expand its regulatory approach to tackling climate change by pushing agencies that don’t typically think about climate change to consider the issue. Gina McCarthy, who rolled out a series of landmark climate regulations as the head of the EPA under Obama, has taken the lead in the Biden Administration on coordinating the push for domestic measures, including at the agencies.

The early dividends of that work is clear already. Janet Yellen, Biden’s nominee to lead the Treasury Department, for example, said she would start a climate “hub” at the department to assess the risks to the financial system posed by climate change during a confirmation hearing Tuesday.

All of these measures will buttress what Biden has promised will be an aggressive effort to promote action on climate change across the globe. In response to the pandemic-related economic fallout, many of the world’s largest economies have doubled down on climate change measures, using recovery spending to fund green infrastructure. The European Union has launched a Green Deal, calling climate change central to its development plans as it commits hundreds of billions of euros to phasing out fossil fuels and building new clean infrastructure. Meanwhile, China has renewed its plans to develop a domestic clean energy economy. A bold campaign from the U.S. could help shape the paths of developing countries like India that are poised to make up an increasing share of the emissions pie.

In his confirmation hearing on Tuesday, Antony Blinken, Biden’s pick to serve as Secretary of State, called climate change an “existential threat” and responded resolutely to questions regarding climate change. He committed to making climate change a top priority in global engagement and vowed to oppose international financing for fossil fuel projects. Biden has further signaled his commitment to making climate central to his international engagement with his selection of former Secretary of State John Kerry to serve in a newly created position of climate envoy.

But to have credibility, Biden will need to enact a robust agenda domestically—and he needs to get started now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com