This article is part of the The DC Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox every weekday.

Almost everything about the deadly insurrection at the Capitol last week will make President-elect Joe Biden’s hard job harder when he takes office next week. But there is one thing it may have eased: the opposition to Biden’s pick to lead the Pentagon seems to be losing steam.

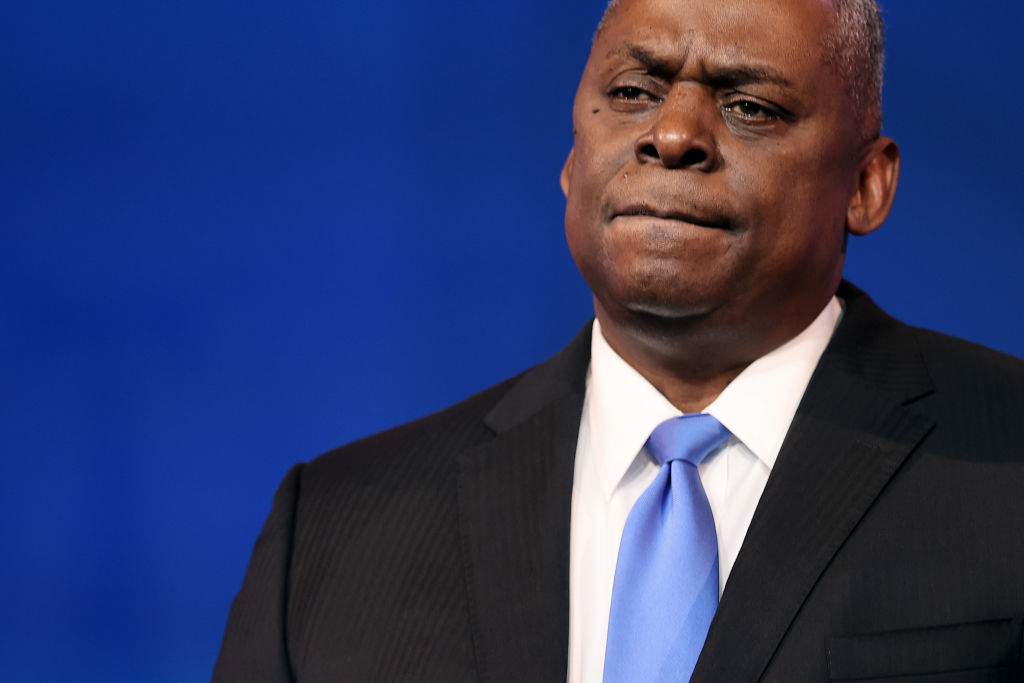

Last month, Biden’s choice of retired four-star Army General Lloyd Austin raised some hackles on Capitol Hill. By law, a civilian must lead the Pentagon, and there is a seven-year cooling-off period for retired military members before they’re allowed to trade their uniforms for a suit-and-tie and come back as the Secretary of Defense. Austin only retired in 2016. He would need Congress to sign-off on a waiver to that law — a move made just twice before, for Gen. George Marshall during the Harry Truman years and for Gen. James Mattis in 2017. (Both, it should be noted, are likely to be remembered for accomplishments away from the Pentagon, and neither lasted two years in the role.)

An accidentally bipartisan group of lawmakers had initially signaled reluctance to grant another waiver for Austin, as it risks cementing a bad precedent and further concentrates power in uniformed hands. After all, it’s not like the Pentagon lacks familiarity with how men and women in uniform think. Incoming Senate Armed Services Chairman Jack Reed said after the Mattis waiver that it was a once-in-a-generation move, hinting that the Army veteran was going along with it only so that President Donald Trump had the most capable internal check on his power. Others like Sen. Tammy Duckworth — a combat veteran and a Democrat — also said the waiver for Austin might not be appropriate. Republican Senators and veterans Joni Ernst and Josh Hawley have also gone on-the-record with concerns.

But all of that was before the bungled response to the siege of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. Investigators will spend months piecing together just where security lapses fell and who should bear the responsibility for them. But for now it appears there was a breakdown among the Pentagon, Capitol police and local police in sending National Guard troops to secure the Capitol Building — and the Vice President inside. There are plenty of worries that Biden’s Inauguration next week could be an even worse sequel with days of violence to follow.

Few would argue there’s ever a good time for a gap in Pentagon leadership and even fewer would say that time is now. That’s why lawmakers are quietly starting to cede some of their early opposition to Austin’s waiver. On Tuesday, Reed, during a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee that he will lead as soon as the two Democrats who won Georgia run-offs take their seats, seemed to back away from his hard opposition.

“We now have a clearly qualified candidate and a declaration by the President-elect that he needs Gen. Austin for the safety and security of the nation,” Reed said. “Civil-military relations are never static and must constantly be tended to. During the four years since the committee last considered such a waiver, the status of the military relations has eroded significantly under President Trump, and the Department of Defense is in many cases adrift.”

In other words, now is not the time to worry about a flip-flop; the stakes are simply too high. In their own way, the rioters who sought to deny Biden power may have actually made it easier for him to get the Cabinet he sought, or at least part of it. After all, it’s tough to argue that a Trump Administration hold-over running the Pentagon is what the country needs right now.

Not everyone appears willing to give Austin a pass. Sen. Jim Inhoffe, the outgoing GOP Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, asked witnesses this week if two Generals in four years was really the best answer for the Pentagon. And Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat, still seems to be a nay on this exemption. Similarly, Republican Sen. Susan Collins is going to have tremendous bargaining power in a 50-50 Senate. Still, that’s not to say there might be opposition to the waiver and support for his confirmation from the same offices. They are, to be fair, very different questions.

House aides expect some of the Democrats who opposed Mattis will support Austin, who if confirmed would be the first Black person to serve as Secretary of Defense. The Congressional Black Caucus, a powerful bloc when unified, has thrown its support behind Austin.

Austin isn’t due to meet with the House Armed Services Committee about the waiver until Jan. 21 — one day after Biden’s inauguration — because of a lack of organization as party power shifts in the Senate. That means Biden will start his term without a confirmed Secretary of Defense, a first since the Senate in 1989 rejected George H.W. Bush’s nomination of John Tower to the role. George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Trump all started with their Defense Secretaries confirmed and ready to run the almost-three-million-employee behemoth.

Biden’s pick of Austin was in trouble over the cooling-off period from the start. With Capitol Hill looking like a war zone and military personnel patrolling the site of Biden’s inauguration next week, maybe, for some lawmakers, that distinction between civilian and warrior matters a little less right now.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the daily D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com