Rev. Raphael Warnock made history when he won the Jan. 5 Georgia run-off election for the U.S. Senate and became the first Black Democratic senator from the South, in a victory that helped the Democrats to regain control of the legislative branch. The high Black voter turnout that was key to electing Warnock and President-elect Joe Biden was the product of shrewd organizing by Black women voting rights activists like Stacey Abrams and a continuation of more than a century of efforts to help Black people exercise their right to vote.

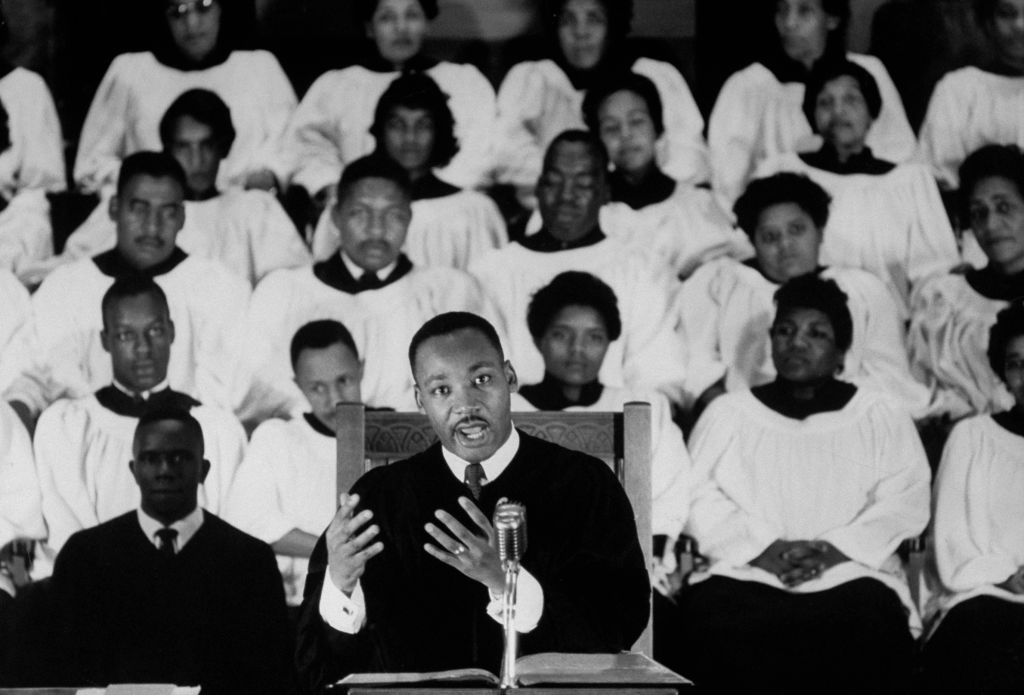

These victories are especially symbolic given that Warnock’s historic win happened a week before Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Jan. 15 birthday and the federal holiday honoring him. King, like Warnock, was a pastor at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Formerly enslaved individuals helped found Ebenezer in 1886, and its roots in civil rights activism predate King. His grandfather, A.D. Williams, was the church’s second pastor, and he helped start the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP. The church’s historian Benjamin Ridgeway tells TIME that King’s father, known as Martin Luther King, Sr., was an early advocate for Black police officers in Atlanta and equal pay for teachers as a pastor at Ebenezer. But Martin Luther King, Jr. helped raise the church’s profile on the world stage.

Ebenezer is the church where King was baptized in 1929 and he credited it for laying the foundation of his success. King wrote in 1950 that Sunday School “helped me to build the capacity for getting along with people.” It was the church where he served as a co-pastor with his father in the 1960s, even preaching there on Bloody Sunday, according to Ridgeway. And it was the church where his funeral service was held on April 9, 1968, five days after MLK Jr. was assassinated. In the Black Lives Matter era, the church has also hosted the funerals of recent victims of police brutality like Rayshard Brooks.

“It’s been a place of freedom, and aspiration for many generations,” as Andrew Young, 88, a veteran of the ’60s civil rights movement and friend of Martin Luther King, Jr., explained to TIME in a recent phone call.

It was 64 years ago this week, in mid-January 1957, when civil rights leaders met at Ebenezer to plan what would become a new chapter of the movement and formed the Southern Leadership Conference on Transportation and Nonviolent Integration (SCLC). They were “using the momentum generated by the 1955-1956 Montgomery bus boycott’s success to create other movements throughout the South,” as an architect of the civil rights movement Julian Bond explained in Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement.

“The church was the only place that Black people controlled and owned, and nobody could censor them, so all our mass meetings were held in churches,” explains Young. “All our civil rights, voter registration training, most of my campaign headquarters and all of the get-out-the-vote efforts were in churches. All the way back to slavery, the natural leadership in the Black community ended up being religious leaders because they were people of more courage and more faith. To this day, politics in a place like this can cost you your life, and the ministers had a base in their membership and they had a place, but then they had the vision and the courage and the faith to take it on.”

Some of the roots of Black support for the Democratic Party from the 1960s onward can be traced back to Ebenezer. At the church, King Sr. made a critical endorsement of Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy over Vice President Richard Nixon in the walk-up to the 1960 presidential election. While the King family had known Nixon better, JFK had made an impression by calling to check in on King Jr.’s pregnant wife Coretta while he was in jail after participating in an Atlanta sit-in.

According to Bond’s book, the elder King told an audience at Ebenezer, “It took courage to call my daughter-in-law at a time like this. He has the moral courage to stand up for what he knows is right. I’ve got all my votes and I’ve got a suitcase, and I’m going to take them up there and dump them in his lap.” JFK won the presidency carrying 70% of the Black vote. That moment and the enactment of 1960s civil rights bills like the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act helped drive white southerners from the Democratic party to the Republican party.

The lessons from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s sermons at Ebenezer, as well as many of the social problems he railed against, still ring true today.

“Now ever since the founding fathers of our nation dreamed this dream in all of its magnificence—to use a big word that the psychiatrists use—America has been something of a schizophrenic personality, tragically divided against herself,” he said from the pulpit on the Fourth of July in 1965, a month before the Voting Rights Act was enacted, MLK called on America to live up its promise. “On the one hand we have proudly professed the great principles of democracy, but on the other hand we have sadly practiced the very opposite of those principles. But now more than ever before, America is challenged to realize its dream, for the shape of the world today does not permit our nation the luxury of an anemic democracy. And the price that America must pay for the continued oppression of the Negro and other minority groups is the price of its own destruction.”

In addition to solemn work of prayer and planning the agenda racial equality at Ebenezer, Young says his “best memory” is about having fun there, celebrating King’s birthday in 1968.

“We had Dr. King’s last birthday party in the basement of that church, and it was sort of a surprise,” Young says. “[King] was getting ready to go away to make a speech, and we said we needed to have a brief meeting before he left. And when he came in, we had a birthday party for him.”

Fifty years later, at an inter-faith service in Baltimore marking the anniversary of King’s assassination, Warnock told attendees that King was supposed to preach at Ebenezer three days after he was assassinated, and had prepared a sermon entitled “Why America May Go to Hell.”

Warnock acknowledged that may sound harsh coming from a proponent of nonviolent resistance, but that shows how common knowledge about MLK tends to be reduced to sanitized platitudes.

“When Dr. King died we resurrected a new Martin Luther King Jr., one who does not make us too uncomfortable,” he said on April 12, 2018. “He was the best kind of patriot because he loved the country enough to tell the country the truth. Now is a time for truth-telling. Now is a time to call the nation to be the best, to stand tall with moral excellence…It’s bigger than Republican politics; it’s bigger than Democratic politics.”

When asked how he thinks King would react to Warnock’s win, Young, who was Georgia’s first Black congressman in more than a century when he took office in 1973, says, “I think he is as happy as he could be. He talked about [how] ‘I may not get there with you, but my people will get to the Promised Land.‘” The U.S. Senate, was “one of the Promised Lands we spelled out,” he says. We felt that the nation was really stifled in every way by the Senators from Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina. And one of the things we set out to do in 1960 was to redeem the soul of America and restore democracy to the South.”

King and Warnock’s call on the nation to be its best is still more timely than ever.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com