If she found the right guy, Kari Arenberg could see herself having kids. But her work was never conducive to dating, let alone to freezing her eggs in hopes of leaving her options open. The 31-year-old event producer traveled constantly between New York City and Los Angeles, with long days lifting heavy boxes and running around venues.

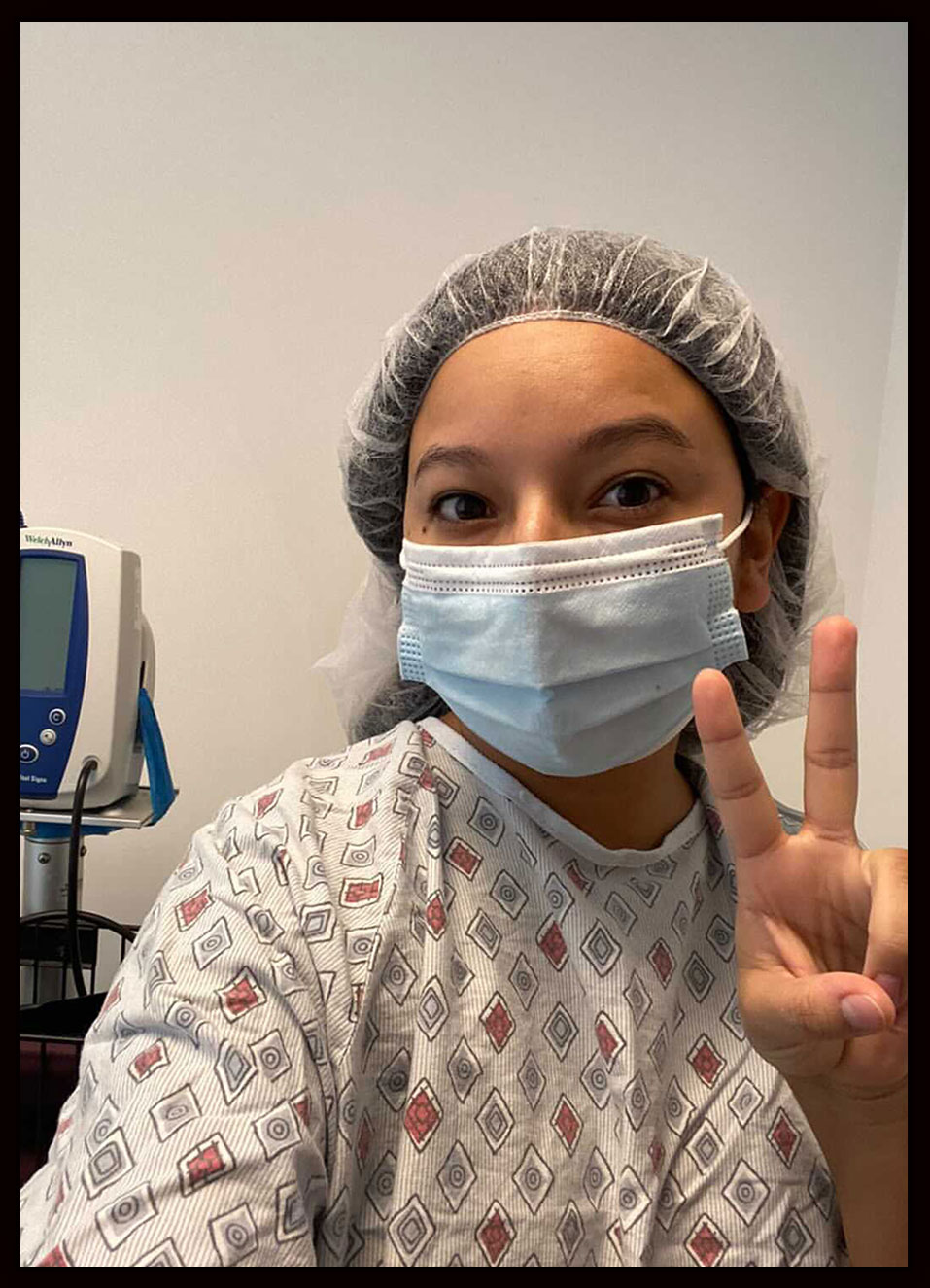

Then, in 2020, Arenberg was furloughed, and the egg-freezing process became, for the first time in her life, logistically possible. She moved in with her family in Chicago and visited a clinic. Soon she was giving herself as many as three shots a day to stimulate her ovaries, and visiting the clinic every few days for bloodwork and an ultrasound to determine when the eggs would be ready for retrieval. She was able to freeze 21 eggs, a feat that likely would have been impossible if she had had to give herself shots while stuffed into airplane bathrooms or trying to schedule visits to the clinic around the national events, like Comic Con, that she produces. “I love my work and want to prioritize it,” Arenberg says. “So it’s ironic that my career also kept me from doing this earlier.”

When the coronavirus pandemic hit, fertility clinics braced themselves for a downturn. People have been avoiding the doctor’s office since the spring, first because they feared exposure to the virus and later because many people who have been laid off or furloughed cannot afford the medical bills. Fertility treatments are expensive, and the cost of egg freezing ranges from $6,000 to $20,000. (Arenberg’s was $12,000—an especially daunting cost after losing work.)

But clinics across the country are reporting an uptick in women freezing their eggs during the pandemic. Though no organization in the U.S. collects national data, 54 clinics across major American cities including Denver, Atlanta and Seattle told TIME that the number of women freezing their eggs has increased year-over-year—an impressive stat considering most of those clinics were forced to shut down and suspend fertility treatments in the early months of the pandemic. An additional five clinics reported the same number of egg freezing cycles in 2020 as in 2019 despite being closed anywhere from one to three months in 2020. Only two clinics told TIME they had seen a decrease in the number of women freezing their eggs since 2019. “We didn’t know what to expect,” says Colleen Wagner Coughlin, the founder of OVA Egg Freezing Center in Chicago. “If anything we expected a downturn. But we’ve seen a huge increase—several hundred more new patients [in 2020].”

At some clinics, the changes have been robust. When TIME collected data in November, Shady Grove Fertility, which runs 36 clinics across the Eastern seaboard, had seen a 50% increase in women freezing their eggs since 2019. Doctors at NYU Langone saw a 41% year-over-year increase in women fertilizing their eggs. And Seattle Reproductive Medicine had conducted 289 egg-freezing cycles in 2020, compared with 242 in 2019, a nearly 20% jump.

Sharon Covington, a therapist who provides counseling services at Shady Grove Fertility Clinic, is “busier than ever” offering mental health support to women considering fertility treatments, including egg freezing. She says the women she sees are freezing their eggs because of the pandemic, not in spite of it. Women who normally travel for work, like Arenberg, are grounded. Those with busy social lives are alone at home. Their schedules are open. But that time in isolation has also afforded space for reflection. “Everybody had to take a hard stop in their lives,” Covington says. “And I think what happened with that is that it gave people the time and the space to kind of reassess their priorities and the directions that they’re taking in their life.”

Many single people feel as if they’ve fallen a year behind on their life plans. Dating was almost impossible at the beginning of the pandemic. Even now, near-strangers must negotiate a difficult social dance with one another when they agree to meet up for a distanced drink—when can they hug, kiss or even just go indoors together? When will they feel safe with one another? “I actually went on a few dates,” says Arenberg, “but sitting outside shivering in Chicago in the winter is not conducive to finding someone.”

Read More: The Coronavirus Is Changing How We Date. Experts Think the Shifts May Be Permanent

Arenberg first heard about egg freezing when the winner of the Bachelor’s 2015 season, Whitney Bischoff Angel, revealed that she froze her eggs. Egg freezing has steadily grown more popular in the years since the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) removed the “experimental” label from the procedure in 2012. Many women were already freezing their eggs for medical reasons, either because they were going through a medical procedure like chemotherapy that could reduce their fertility or had a medical condition like endometriosis that could negatively impact ability to conceive. But with the change in labeling came the rise of what doctors call “social egg freezing”—women who freeze their eggs simply because they aren’t ready to have a child yet. In 2009, just 475 women froze their eggs, according to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. By 2018, 13,275 women did so, an increase of 2,695%.

The spike comes thanks in part to celebrities like Chrissy Teigen, Michaela Coel and Emma Roberts sharing their own egg-freezing stories. Kourtney Kardashian went so far as to film her egg freezing preparation on Keeping Up With the Kardashians, and Amy Schumer shared pictures of her bloated and bruised stomach as she took the shots this summer to freeze her eggs as part of her IVF process. They’ve demystified a process that was little known just a few years ago, including, in Schumer’s case, the most uncomfortable aspects.

René Hurtado, a 28-year-old in Scottsdale, Ariz., knew that she might have to stay home in the weeks before her egg retrieval in case she suffered side effects like cramping or headaches, and believed the pandemic would be the ideal time to nurse those pains without missing meetups with friends. “On day five of injections, I couldn’t even walk. I only felt good if I was lying flat on my bed,” she says. She had to take several days off from her job at WeWork while she recovered. “In an alternate world, I was supposed to be in Miami for a bachelorette party that week. Thank God I did this during COVID so I didn’t have to see anyone or go anywhere because I was in so much pain.”

Hurtado’s company offered egg freezing as part of the benefits package, a perk that’s become increasingly popular among startups as a means of attracting women workers (or, in critics’ eyes, pressuring workers to prioritize work over family). But the trendiness of egg freezing in Silicon Valley may be reaching its peak. Some doctors have cast doubt as to whether companies will continue to offer this costly benefit when many organizations are choosing between cutbacks and layoffs. Wagner Coughlin, the founder of OVA in Chicago, said that her organization is already looking into a new payment structure in anticipation of companies’ dropping the benefit.

Michael Jacobs, a doctor at the IVF Center of Miami, believes that moment has already arrived. He was one of the few doctors who told TIME his clinic was seeing a downturn in egg-freezing rates. “In cities like New York and Los Angeles, maybe there are more people who can afford the cost of egg freezing right now,” he says. “But I think a lot of people here are just worried about paying their bills.”

The high price of egg freezing has long meant only a specific subset of patients—mostly upper class, and mostly white—pursue the process: a study of nearly 30,000 egg retrievals by ASRM found that just 4.5% of the women who underwent the procedure described themselves as Hispanic and 7% identified as Black.

Read More: Women Are Deciding Not to Have Babies Because of the Pandemic. Why That’s Bad for All of Us.

Pavna Brahma, a doctor at the Shady Grove clinic in Atlanta, theorizes that this may be the boom period before a bust. “People are coming in who are worried about losing their job or their coverage or their insurance,” Brahma says. “They want to take advantage of the moment when they know they have coverage and economic stability in their job.”

She stresses to her patients that waiting until they receive the vaccine to freeze their eggs is a viable option: “Two to six months rarely makes a huge change in their fertility. I don’t want women to feel pressured by the pandemic.”

Still, pandemic or not, time remains a key driver in women’s family-planning decisions. As a general rule, the younger you are, the more eggs you have, and the more likely an egg-freezing process will be successful. Many women fear the benchmark of 35 years old. Loss of eggs and risks to pregnancy happen gradually over time, not all at once, but 35 is when doctors begin calling pregnancies “geriatric” to reflect increased risks. It’s also the age at which fertility doctors will advise freezing more eggs, often through several procedures to harvest as many eggs as possible and improve the chances that one can be fertilized later.

Bryn Woznicki, a 33-year-old filmmaker who lives in Los Angeles, has always known she wants to be a mother, “but every year,” she says, “it’s a ticking time bomb working against your biological clock.” When filming work dried up last spring and dating became more difficult, she took stock of what turning 34 during a pandemic could mean. “Say I met someone today,” she says. “Say I really liked them and we got married. By the time I did that and enjoyed my partner and we decided to take on this huge responsibility of having kids, that’s another few years down the line.”

With her work and social life on pause, she decided to divert some of her savings towards a potential future family. “I had some money saved to try to move to New York this fall and then, you know, COVID happened,” she says. “Meanwhile I was feeling the pressure from my biology telling me that time was running out, and I was like this is the one thing I can control in an unpredictable year.”

For Arenberg, being able to freeze her eggs was a “silver lining” of the pandemic. “As unfortunate as it is that I’m technically unemployed, this really gave me the mental capacity to look ahead for the first time,” she says. “I don’t know if I want kids, but maybe if I meet the right person some day, this just provided a nice comfort level where I can make some decisions about dating and kids and work when things get back to normal.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com