Shelby Parker planned to get pregnant this year. The timing seemed right: She was working as a middle school teacher in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, a job that provided benefits for her whole family. Her husband, who drives a truck for FedEx, had just gotten a promotion. Their 21-month-old daughter was nearly ready for preschool.

Now Parker, who is 29, is contemplating not trying for a second child at all. The state, deprived of tax revenues because of business closures resulting from the coronavirus, slashed its budget and cut public-school funding by $300 million. The school has warned teachers that there may be a round of layoffs before the end of the year. As the pandemic rages on, she and her husband worry that she could end up out of work. If that happens, they’ll be left without health insurance.

If things were different—if Parker had confidence in the economy, in her chances of staying virus-free on the days she teaches in person, and in the ability of the nation and Ohio to control the spread of the coronavirus—she’d be pregnant already. “I’m grieving for the family I thought I would have,” she says.

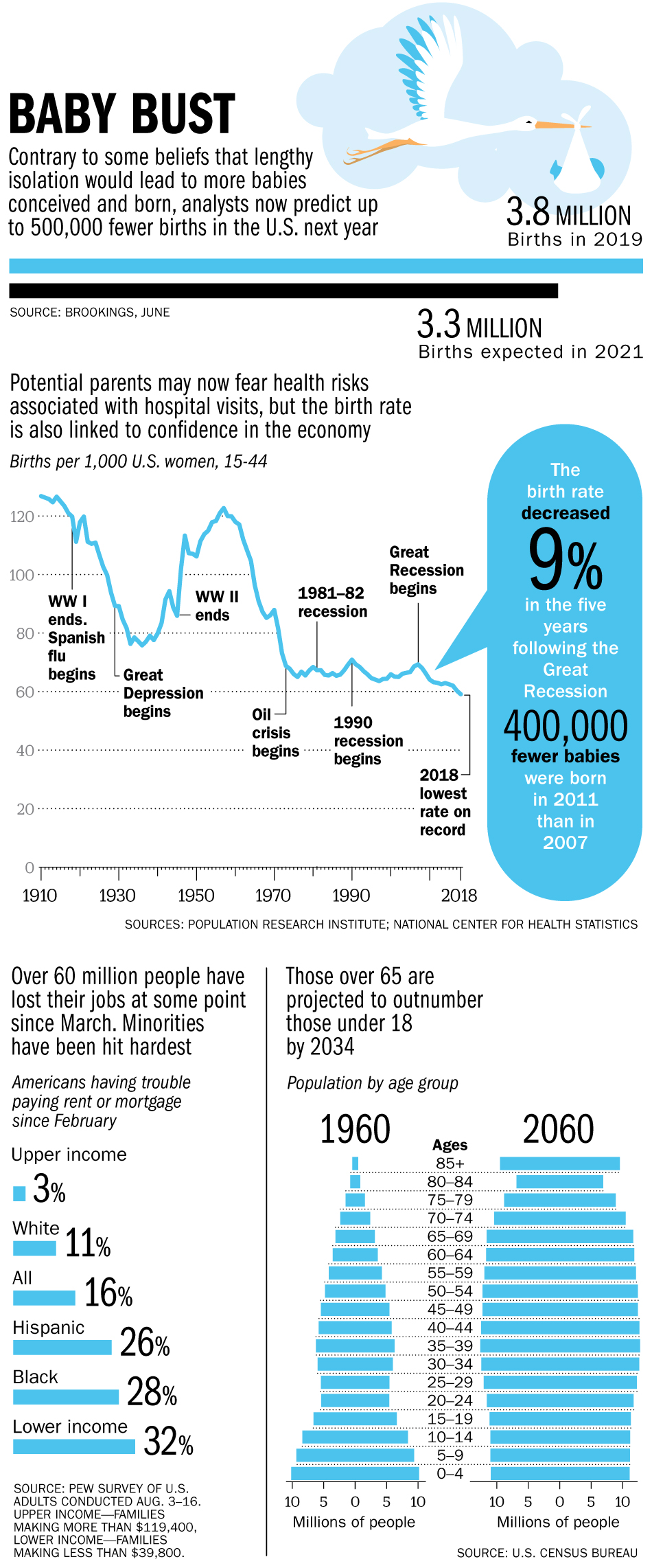

Economists and fertility experts say hundreds of thousands of American women are making the same decision. A June report from the Brookings Institution estimated that the U.S. would see as many as 500,000 fewer births in 2021, a 13% drop from the 3.8 million babies born in 2019. Telehealth clinic Nurx tells TIME it has seen a 50% jump in requests for birth control since the beginning of the pandemic, and a 40% increase in requests for Plan B. A survey from the Guttmacher Institute found that 34% of sexually active women in the U.S. have decided to either delay getting pregnant or have fewer children because of concerns arising from COVID-19. Lower-income women were much more likely than other women to want to put off having a baby; that’s especially true among Black and Latinx women, who have suffered disproportionate income and job losses this year.

On top of financial worries, the pandemic has plagued would-be mothers with a host of other concerns, including hospital rules that might banish partners from the delivery room and the risk of exposing relatives to illness if they’re needed to provide childcare. And of course, parents are worried about the health of the baby: Los Angeles County recently reported the first newborn cases in the U.S., with 8 of 193 babies testing positive for COVID-19. Katie Hartman, 34, lives in Florida, one of the states hardest hit by the coronavirus, and is considering a home birth if she does decide to get pregnant. “You never know when another spike will come, and it just seems wise to avoid the hospital,” she says.

The long-term impact of such delays could be staggering. The U.S. fertility rate is the lowest it has been since 1985. We’re also a relatively elderly nation; by 2034, Americans over age 65 are expected to outnumber those under 18 for the first time in U.S. history. Already, the country faces a severe dearth of workers able to drive the economy and care for our aging population.

Demographers and women’s-rights advocates alike say the looming baby bust is a damning indictment of the health care and childcare systems in the U.S. America is the only developed country that does not guarantee paid leave to new parents, and it does not offer universal childcare or universal pre-K. “COVID set off a bomb in the middle of these jerry-rigged ways of getting by in this country that individual families had created,” says Emily Martin of the National Women’s Law Center. “It’s no wonder parents don’t want to deal with having a newborn right now.”

A July survey from the Mom Project, a startup that works to pair mothers who have dropped out of the workforce with new jobs, found that U.S. moms are twice as likely as dads to leave their jobs in 2020 because of the strains of juggling work and family care since the pandemic began, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that four times more women than men dropped out of the workforce in September alone. Studies show that women who leave the workplace, even for just a year, suffer financial consequences for the rest of their lives.

Now, after decades of fighting for equal pay and equal opportunities in the workplace, women are once again left with a choice: Have a career or have a baby?

With everything being so iffy and businesses closing and layoffs, would I have a job to go back to?

Margaret Ogden, a 33-year-old lawyer in Richmond, Va., had been waiting until her husband, a doctor, finished residency before trying to get pregnant. She figured she could lean on her mother for childcare help. Now that her husband is working in a hospital where he might be exposed to the coronavirus, her plan is on hold. Asking her mother to stay with them to babysit is out of the question, and Ogden, who is working primarily from home, knows she’d likely be left to juggle childcare and work largely on her own. “As a lawyer you can’t really work part time, and full time is a lot more hours than some other professions,” she says. “I have friends who are honest and vulnerable about what’s happening right now, and they feel like they’re not being good parents or good employees.” Even before the coronavirus placed new burdens on moms, she saw high-powered female lawyers forced to take on less ambitious work when they had children. The ones who stayed displayed grit and resolve that seemed possible but difficult to emulate.

“Choices for working couples were never great to begin with,” she says. “They’re impossible now.”

The situation is worse for would-be parents who don’t have the option of working from home. Aaron Jarvis, 33, has an endometriosis diagnosis that could make getting pregnant difficult, so she and her husband Marty discussed starting their family soon. But Jarvis, who works in human resources in Detroit, and her husband, who works at Chrysler, were told they must come in to work despite the pandemic.

Even if she felt comfortable going to an office while pregnant during a pandemic, Jarvis had to wonder how the family would manage after the baby was born. Taking vacation days to care for an infant would be financially risky. “With everything being so iffy and businesses closing and layoffs, would I have a job to go back to?” Jarvis asks.

And then there’s the issue of accessible childcare. The childcare industry has been slammed by the pandemic, according to a July survey from the National Association for the Education of Young Children. It predicted that without substantial government investment, 40% of childcare programs surveyed would be forced to close because of low enrollment and higher operating costs. “We decided we’re probably not going to have a kid until coronavirus is gone gone,” says Jarvis. “And that might be a few years. And that’s O.K.”

But demographers say that if women delay having babies at any point in their lives, it’s more likely that they won’t have babies at all or won’t have as many as they originally planned. “Women see a major crunch because they have to complete their education, get their careers started, find a partner and have babies—if they plan to do that—in just a 10-year span,” says Dowell Myers, the director of the Population Dynamics Research Group at the University of Southern California. Even as advances in health care and technology have allowed women to delay pregnancy, women are having fewer babies total than their mothers and grandmothers did.

Millennials, the 24- to 39-year-olds who are most likely to consider having a child right now, already had their life plans delayed because of the Great Recession. They’re achieving career milestones later, buying houses later and having kids later than previous generations. Myers says that if hundreds of thousands of millennial women choose to delay pregnancy even longer—until the arrival of a vaccine, a downturn in cases in their area or a return to “normalcy”—then “we’re looking at a fundamental and unprecedented change to our population.”

Many women are asking existential questions about whether they should bring a child into such a scary world. Haley Neidich, a 35-year-old therapist in South Pasadena, Fla., has decided not to get pregnant until “the pandemic is over,” but she’s still trying to figure out what “over” means. Her previous two pregnancies—one of which ended in miscarriage shortly before she began to quarantine—were tough. She experienced debilitating nausea that, if she were to get pregnant again, would make it hard to care for the toddler she already has. She has nightmares about the possibility of another miscarriage and being forced to go to the doctor alone for a heartbreaking surgery if that came to pass.

But with no end date for the spread of COVID-19 in sight, that may be a risk she has to take. “I still believe in a world where I go to brunch and get to take pictures of my pregnant belly with my friends,” she says. “But maybe for women 35 and older, that’s unrealistic. That’s not going to be the reality of pregnancy in the near future, and maybe I need to adjust my expectations for what pregnancy is.”

“The birth rate is a barometer of despair”

Early in the pandemic, many would-be parents assumed that quarantine would be temporary, delays in plans minimal. “Everyone’s initial reaction was there was going to be a baby boom because there’s only so much to watch on Netflix,” says Phillip Levine, a professor of economics at Wellesley College in Massachusetts and co-author of the Brookings study predicting a baby bust.

That carefree version of quarantine was a fantasy. More than 215,000 people have died in the U.S., and the pandemic continues to rage out of control. At its peak, more than 40 million people in the U.S. were unemployed. “If you don’t have enough food, you’re probably not thinking this is a good time to have a kid,” says Levine.

The Spanish flu of 1918 is the only real modern comparison point for the current COVID-19 crisis. Levine and his co-author, University of Maryland economics professor Melissa Kearney, examined the data from that time and found that major spikes in death rates during the two-year pandemic corresponded with a 12.5% decline in birth rates nine months later.

But in 1918, America was in the midst of World War I and factories were open: the country was not facing the same unemployment rates that we do now. Recessions, like the one the U.S. is currently in, also tend to lead to precipitous drops in birth rates. After the Great Recession in 2008, America saw a 9% decrease in the birth rate over the course of five years, with about 400,000 fewer babies born in 2011 than in 2007. States that were hit harder by the recession saw more dramatic declines. Levine and Kearney have found that every 1% increase in unemployment translates to a 1.4% drop in birth rate.

There are additional reasons to expect the birth rate to drop this year: stress, which is bad for fertility, and access to birth control, which did not exist in 1918. Surveying the available data, Brookings estimates 300,000 to 500,000 fewer births in the U.S. next year compared with this year.

Birth rates in America had been dropping for 34 years prior to 2020, except for a brief uptick in 2017, and recently fell below replacement level, the fertility rate that would keep the size of the population the same from one generation to the next. Ideally, age distribution in a population looks like a pyramid, with fewer older people at the top and a larger base of young workers at the bottom. For the first time in American history, that distribution is changing. From 1970 until 2011, the ratio of seniors (ages 65 and older) to working-age people was steady at 24 to 100, according to a calculation by Myers. Now, that ratio looks more like 48 to 100. “There is twice as heavy a load of older people as before,” he says. “If you then have shrinkage in the number of babies born, you’re going to undermine this ratio even more in future years.”

The long-term implications are frightening. Fewer students means many institutions of higher education will be forced to close without sufficient incoming tuition, leading to a further inequity in the system. Fewer workers means a lower GDP and fewer people contributing to Social Security. Fewer young people means fewer soldiers to recruit to the military.

When birth rates fell to a 32-year low in 2018, despite economic growth, demographers puzzled over why people were putting off pregnancy or deciding not to have children at all. At the time, Myers said, “the birth rate is a barometer of despair,” explaining that young people will not plan for babies if they are not optimistic about the future. Now, he says, we’ve reached a new level of despair.

Have a baby or have a career

Women’s-rights advocates say the alternative to a major drop in birth rate may be a mass exodus of women from the workforce as couples decide which parent should provide the full-time childcare. One in four women is considering downshifting her career or leaving the workforce because of COVID-19, according to a Lean In and McKinsey survey of 12 million workers at 317 companies. It’s the first time in six years of conducting this annual study on women in the workplace that the researchers have seen evidence of women intending to leave their jobs at higher rates than men. Across industries in the U.S., women still get paid less than men, so most couples calculate that it makes financial sense for the woman to step back. “In two-partner households, we’re seeing men’s careers take the priority—for economic reasons but also really ingrained social reasons,” says Allison Robinson, CEO of the Mom Project. “That leaves women to make the tough choices.”

As Jarvis contemplated whether to get pregnant this year, she watched her friends in Detroit give birth and then struggle to balance work and newborns. “It was just fight or flight,” she says. “Even if you can work from home, and that’s a blessing, I see their kids running around in the back of video calls or crying and think, How sustainable could this actually be?”

When women leave work—even for just a year, as many mothers are considering now—their long-term earning potential plummets. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research conducted a study that found the earnings over time of women who took just a year off work between 2001 and 2015 were 39% lower than those of women who didn’t take time off. The exit of large numbers of women from the workforce is bad not just for individual women and their families. It’s bad for the economy as a whole, because women had surpassed men to make up the majority of the U.S. workforce earlier this year before the pandemic hit. (They dropped from 50.04% to 49.70% in the wake of this year’s job cuts.) “We need to make it as easy as possible for women to balance child-rearing and their careers,” says Myers. “It’s not about individual women. It’s about the fate of the country.”

But America is particularly ill-equipped to support mothers through this moment, especially those who cannot work from home and who must pay increasingly steep rates at day-care centers that are shrinking their class sizes and upping their prices to survive. “Gender inequity is a worldwide problem,” says Martin of the National Women’s Law Center. “But what we don’t see in other countries but do see in the U.S. is the way having a child is closely associated with a real risk of poverty.”

The pandemic has shone a new light on our long gestating childcare crisis: Joe Biden has proposed free pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds as part of his presidential platform, in addition to childcare tax credits for some families and financial help for the childcare industry.

The Mom Project has begun working with American companies to institute policies that would allow parents, and mothers in particular, more options: flexible schedules for mothers who cannot log on until after their child has gone to sleep, for instance, and part-time shifts as long as the pandemic lasts to ensure they can watch their children without losing out on crucial work experience. The Mom Project also partnered with several of America’s largest corporations to create a $500,000 fund to provide grants to companies to save working mothers’ jobs.

Robinson points to tech companies, which have fared better than most sectors this year, as leaders in the effort to accommodate working parents. Google, Facebook and Salesforce have offered extra time off to parents. (Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, with Lynne Benioff, is the co-owner and co-chair of TIME.) Amazon, Netflix and Nvidia are paying for employee memberships to services like Care.com, which provide backup childcare to parents. Twitter set up a virtual summer camp for employees’ kids that could be replicated by other companies for the school year. Microsoft piloted a four-day workweek in Japan last year and reported a 40% boost in productivity from workers in those offices, and the Mom Project is advocating for companies to mimic that program in the U.S.

But as long as the pandemic lasts and children are home from school and day care, these solutions are mere Band-Aids. “I have not seen anyone come up with a bold solution to this problem,” Robinson says. “For single moms, moms who rely on hourly wages, moms with kids home from school but without access to wi-fi, it’s a matter of survival.”

Women have largely been left to fend for themselves. Parker has returned to teaching, part time over video chat and part time in person. She worries that if one kid in her class tests positive for COVID-19, she will be asked to quarantine at home and use up the vacation days she had carefully saved for a future maternity leave. Everything about her future—her work, her economic stability, her family plans—feels precarious. “At a certain point, we have to draw a line,” she says. “Are we going to take our chances and try to conceive, or do we just say no more kids? Probably no more kids. It’s the smart move. But I’m just so angry.”

With reporting by Mariah Espada and Simmone Shah

Correction, October 27

The original version of this story misstated Aaron Jarvis’ preferred name. It is Aaron Jarvis, not Aaron Whitaker.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com