The city of Gainesville, Georgia is often called the “poultry capital of the world.” Across Hall County are more than a dozen meat processing plants that employ thousands of workers, many of them Latino and Black. With limited public transportation options and Georgia law requiring employers provide just two unpaid hours for staff to vote, many working-class residents rely on polling sites nearby to where they work or live to cast their ballot.

During the 2020 general election, those who work at a Fieldale Farms Corporation poultry plant in Murrayville, close to Gainesville, could cast their ballot during their lunch break at a nearby polling site at the Murrayville Library—just a four-minute drive away. But the location has been closed ahead of Georgia’s pivotal Jan. 5 Senate race along with three other early in-person voting sites in Hall County. The Murrayville library was opened as an advance voting site for the 2020 general election, although the county has traditionally only had one location for early voting with the exception of statewide Saturday voting, according to county election officials. Tom Smiley, chairman of the Hall County Board of Elections, says the Murrayville location was among the eight locations used as an early voting site for the general election because of social distancing guidelines and large turnout projections.

The next closest voting location is more than seven miles away and there’s no easy way to access it via public transportation. Alarmed civil rights advocates expressed concern that four of the eight locations in Hall County that were open during the general election will not be open for the runoff election despite similarly large turnout figures across the state and the pandemic still raging. LatinoJustice, GALEO, the ACLU and others wrote in a Dec. 16 letter to Hall county’s election officials that these closures would make it “difficult, if not impossible, for many Latino and Black voters” to cast their ballot at advance voting locations, adding that “Georgia’s Latino residents are nearly twice as likely to live in poverty.”

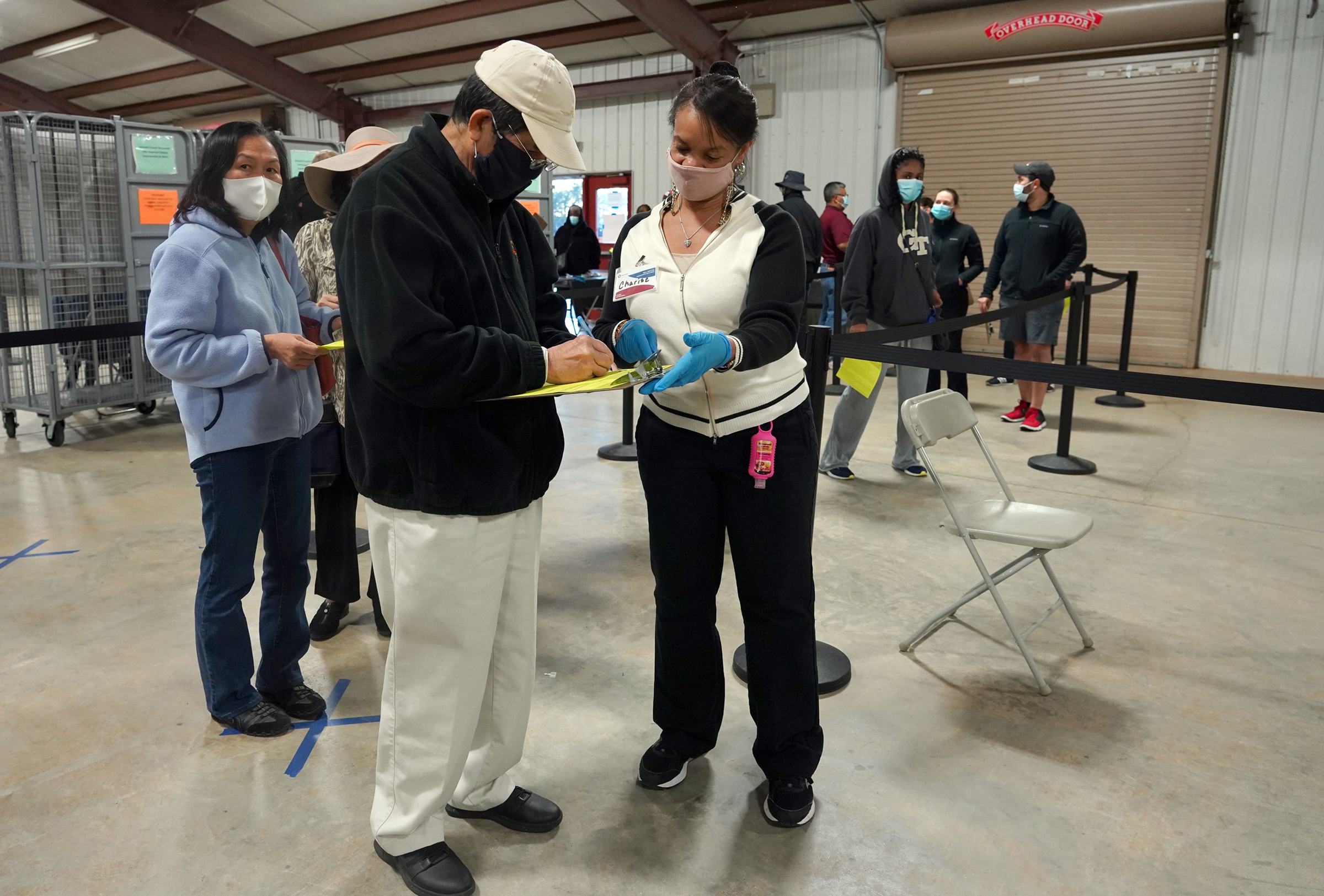

The groups specifically expressed “deep concern” about the elimination of early in-person voting sites at the Chicopee Woods Agricultural Center Activity Hall in Gainesville, which served voters in the cities of Gainesville and Oakwood—both more than 30% Latino—and the library in Murrayville. At a minimum, it requested the county re-open at least two polling sites and says the current arrangements “exposes Hall County to litigation.”

It’s not just Hall County that has attracted scrutiny for reducing its number of in-person voting sites during the pandemic. Civil rights advocates have expressed concern about the implications for voters’ safety because of the pandemic and their access to the ballot because of early voting poll closures in at least five counties—Hall, Chatham, Liberty, Cobb and Forsyth. “Any reduction in early voting availability will contribute to longer lines and…that presents safety issues,” says Michael Pernick, an attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “It’s concerning to have long lines in the age of COVID, which disproportionately affects communities of color.”

Georgia saw record turnout in the 2020 general election with more than 4.9 million votes cast. Enthusiasm for the state’s Senate race remains high as more than 1.8 million votes have already been counted. At this point in the general election, that number was just over two million, according to Georgia Votes. “The numbers show that Hall County’s decision to close early voting sites is suppressing voter turnout,” Pernick said at a press conference Wednesday, pointing out that Hall County was on the higher end of voter turnout in the state’s general election during the early voting period but is now lagging behind most of the state “by a substantial margin.”

As the pandemic continues, early-in person voting has emerged as an option to alleviate and avoid the longer lines on election day and reduce voters’ potential exposure to COVID as well as a solution for those worried about mail delays, the letter notes. The margins in the two Senate races are expected to be razor thin and their outcome will determine which party controls Congress’ upper chamber. A difference of a few thousand votes could be enough to tilt the race and fate of the U.S. Senate one way or another. Hall County is home to more than 12,600 Latino citizens of voting age and more than 9,900 Black citizens of voting age. About 29% of Hall County’s population is Hispanic or Latino, per the census.

Read more: Why It’s a Mistake to Simplify the ‘Latino Vote’

Given that Georgia law only requires employers to give staff up to two unpaid hours to vote, having adequate access to polling sites is an issue that cuts not only across race but also across class lines, says Pearl Dowe, a political science professor at Emory university. Working class residents may lack the time, ability or means of transportation to cast their ballots farther away. “Closing polling places is a deterrent, even when a person has a car,” Dowe says. “The idea of getting in line at 5 or 6 a.m. when it’s 30 degrees and not knowing how long you’re going to have to stand in that line, that’s a deterrent for many people.”

Polling site closures in Georgia made national news earlier this month when Cobb county announced that it would be closing more than half of it’s early in-person voting sites that were operating ahead of the 2020 general election. The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, ACLU and others wrote in a Dec. 7 open letter to county election officials pointing out that four of the closures “would have severely reduced Black and Latinx county residents’ access to early voting.”

Following mounting pressure, Cobb county decided to add two additional voting sites and switch a third location after first maintaining that staffing and training issues would prevent them from expanding locations. “It wasn’t until there was an overt threat of litigation did the county agree to take steps to mitigate the situation,” Pernick says. Although the organizations behind the letter said they appreciated the steps, they stated they were “insufficient” as Cobb had some of the lowest turnout in the state but voters were experiencing “wait times as long as 120 minutes.” They asked to restore additional early voting locations, provide weekend voting at all locations and expand hours of advanced voting. The county maintains that lines have remained relatively short.

Election officials in counties that have reduced in-person voting sites since the general presidential election have said they lack the staffing or training resources to maintain as many sites as before, although civil rights groups have offered to help train and recruit poll workers. In Cobb, elections director Janine Eveler said in a statement “between COVID, the workload, and the holidays, we have simply run out of people.”

Hall County offered a similar rationale in an emailed statement to TIME. Smiley, chairman of the Hall County Board of Elections, says that the board considered the availability of poll workers given the holiday schedule and staff concerns about COVID-19 in deciding which polling sites to operate. “We can only open enough early voting polling locations as we have poll workers available to staff them,” Smiley says. “The number of early voting locations was not reduced for the runoff; rather they were expanded for the presidential election given our expectation of turnout.”

Regardless, working class residents of Hall County may find it difficult or impractical to cast their ballot farther away. “You have to look at it practically from the shoes of somebody who lives below the poverty line, doesn’t have access to a vehicle, who feels unsafe voting on election day because of the number of people who are going to be there during a pandemic,” says Miranda Galindo, senior counsel at LatinoJustice, one of several advocacy groups that signed off on the Hall County letter. “Disproportionately—where these closures were located are especially harmful to Latinos and so it’s just heartbreaking to think this vulnerable Latino population in Hall County is not going to have equal access to exercising their democratic voice in this critical election of national importance.”

Lana Goitia-Paz, a voting rights organizer with ACLU Georgia who lives in Hall County and helped draft the letter, stressed that it was important to highlight the impact to the Latino community who would be affected by no longer operating an early in-person voting site at the Murrayville library and Chicopee Woods Agricultural Center Activity Hall in Gainesville. “It felt important that if we were going to be asking for something that we would be emphasizing the two sites that could make the biggest impact,” she says. “This is not just an issue of ballot access. It’s also an issue of health (given) higher COVID rates in minority communities.”

Elton García-Castillo, a 24-year-old field coordinator with GALEO in Hall County, was born and raised in the area. When he turned 18, García-Castillo says he didn’t want to vote because he felt his vote didn’t matter. Now, he’s canvassing neighborhoods and leaving door hangers outside people’s homes to remind them to vote. The closure of the Murrayville library polling site could lead to confusion among voters, he says. “When there’s confusion and frustration, they’re likely to think-I’m not even going to do it, especially if they don’t have time and are working at the poultry plants,” García-Castillo says. “Not everyone has a car,” he adds, explaining that many workers rely on sharing taxis and splitting fares to get around.

Georgia Familias Unidas has been providing face masks and voter information kits to some factory workers in Hall County to encourage them to vote. In recent years, more Black and Latino adults have been registering to vote, showing that there has been untapped potential among these demographics. A Pew Survey published Monday found that Black, Latino and Asian Americans have been key to Georgia’s registered voter growth since 2016. The number of Black registered voters increased by 25%—up by 130,000—between Oct. 11, 2016 and Oct. 5, 2020. The number of Latino registered voters increased by 18%—up by 95,000—during the same period.

The closure of early, in-person voting sites has also raised alarms in Forsyth County, which stopped operating six early voting locations in Forsyth County ahead of the Senate elections. Advocacy group Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta sent election officials a letter on Dec. 11 expressing concern about a variety of issues, including the poll closures and language access. “When you do things like close early voting sites, you impede upon increased voter turnout (and) voters who are members of the working class, especially in places like Forsyth where the voting location hours are 8-5,” says LaVita Tuff, policy director at Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta. Tuff notes that voters whose first language is not English may also struggle, especially with changes in polling locations, she says.

Although civil rights advocates say they are appreciative of the work put in by election officials, they feel there is too much at stake to not ensure equal access and safety for voters. “Without hyperbole, this literally is a matter of life or death,” says Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter. “You’ve got people traveling farther distances, waiting in longer lines and with every polling place they close, they’re increasing the chance of somebody getting exposed to COVID.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com