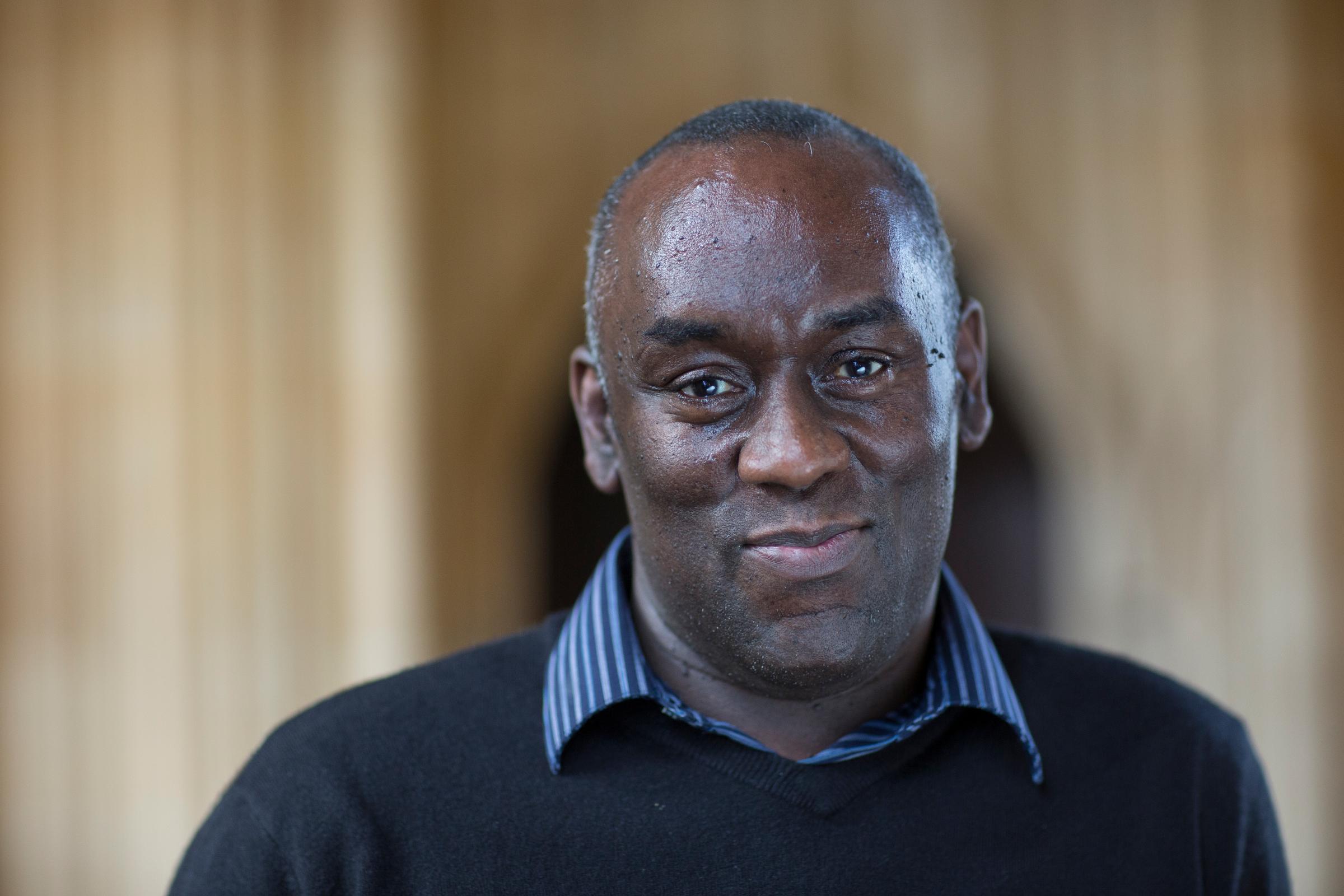

When British novelist Alex Wheatle started work in the writers’ room for director Steve McQueen’s new project Small Axe, he had no idea that his own life experiences would end up as the inspiration for small-screen drama. Wheatle recalls that when the writing team first met five years ago to work on the anthology of five films about West Indian immigrants in the U.K., McQueen said he wanted to explore the story of a young man who had experiences in British institutions such as prisons or care homes. Another writer familiar with Wheatle’s story suggested it would be a perfect fit—the next day, Wheatle brought copies of his social services files to the room. McQueen was immediately sold on the idea, though the writer felt overwhelmed at the prospect. “I was a bit hesitant to be honest, because these are my most personal, awkward, traumatic moments on the screen,” Wheatle tells TIME now. “It took me time to get used to that idea, but now it’s an honor, it really is.”

Born to Jamaican parents in 1963 in Brixton, South London, Wheatle spent much of his childhood in a children’s home in nearby Croydon, before moving back to Brixton to live in a young person’s hostel in the late 1970s. It was there that he found a sense of belonging among the West Indian community, becoming involved in the reggae music scene and performing under the stage name of Yardman Irie. In 1981, he participated in the Brixton uprising, and served four months in prison for his involvement, where he shared a cell with a Rastafarian man named Simeon who became a mentor to him. These experiences are dramatized in the eponymous Alex Wheatle, the fourth installment of McQueen’s Small Axe series airing one per week on Amazon Prime from Nov. 20 through Dec. 18. “At points I was thinking, ‘should I really commit to this?’” says Wheatle, reflecting on being featured in the film. “But I felt that in the end, my story could really help inspire others who may be in a similar position. That’s also what I’ve wanted to do in my writing ever since.”

Alex Wheatle’s early life

Wheatle is today an accomplished and award-winning author, having written more than a dozen books, including children’s and young adult novels, as well as writing and performing a play about his life titled Uprising. But parts of his childhood were deeply painful and have been difficult to revisit and process. In 2014, he spoke out about the systematic physical, sexual and emotional abuse that he suffered while in care at the Shirley Oaks children’s home. Earlier this year, an inquiry found that hundreds of children were targeted by pedophiles working at the home and were subjected to prolonged sexual, physical and racial abuse.

Following those difficult early years, Wheatle moved to Brixton to a young person’s hostel where he finally felt a sense of belonging that had eluded him. There were still times of loneliness too; one scene in the film depicts Wheatle, played by Sheyi Cole, joining a friend and his family for Christmas dinner, and remaining silent during all the noise of family commotion. But ultimately, as he spent time and made friends within that community, he felt a sense of growth from the shy and naive young teen he had been before. He compares the experience to the scene in The Wizard of Oz where Dorothy wakes up in Oz and sees the bright technicolor landscape—vastly different to her previous black and white world. “That’s what Brixton felt like to me, all this color and vibrancy,” Wheatle says.

The 1981 Brixton Uprising

At the same time, Wheatle was living during a period of tense race relations in Britain; these experiences have informed his writing, particularly in his early novels Brixton Rock and East of Acre Lane. The uprising in Brixton in April 1981 resulted from a mixture of underlying tensions, including disproportionate and racist policing of young Black men, economic deprivation and high unemployment, and the apparent lack of investigation and indifference toward the 13 young Black people who had died in a fire at a house party three months earlier in the nearby New Cross area.

“Many of us were angry,” says Wheatle, recalling the aftermath of the fire that sent shockwaves through the community. “That was all on our minds, because we believed that could have been any one of us, we partied the same way they did.” McQueen too remembered the era well, and “energy that was put upon you when you walked down the street as a Black person.” Wheatle says that it was when the London Metropolitan Police started “Operation Swamp,” which used stop and search powers to target Black youths, that the pressure intensified. “It was becoming intolerable. It was almost like living in an occupied town—you could get arrested for looking into a shoe shop or trying on shoes,” Wheatle says. “It was just too oppressive, and something had to break.”

It broke on April 10, 1981, as the police were accused of failing to properly respond to and get medical attention quickly enough for a young Black man who had been stabbed and later died. As a large crowd gathered in protest, more police arrived and the scene escalated into violence. Over the course of the three days of the uprising, more than 279 police officers and dozens of civilians were injured, over 100 cars were damaged and 82 people were arrested. TIME reported that the “riots [stirred] a wave of anguish and recrimination…London now bears a more lasting scar: the psychic damage from the worst race riot in British history.” For Wheatle, watching the filming of the riot scenes for the film was an empowering experience, and brought back his memories of the time. “I remembered that feeling of exhilaration, because finally in front of my eyes, the police were on the defensive and were running away,” he recalls.

Wheatle’s experience in prison and as a successful writer

Wheatle was arrested after the uprising and sentenced to a four-month prison sentence for his participation. It was there that he met his cellmate, Simeon, who would become a huge influence on the young Wheatle, who was carrying bitterness and anger about what had happened to him during his childhood and adolescence. “Slowly and surely, I began to listen to him and what he said began to make sense, and started to instill a belief in me that I could make a change,” recalls Wheatle, speaking about how Simeon introduced him to The Black Jacobins, a 1938 book by Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James, that tells the history of the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804. The book marked the first time he felt was presented with a history that felt relevant to him. After that, Wheatle recalls asking Simeon whether he had any more books about his identity, history and ancestors, which led to more conversations and a greater sense of political and historical engagement. “It was a very good time for me, because I came out a lot more educated than when I entered,” says Wheatle.

As a way to process how he felt after leaving prison, Wheatle began to write poetry, and then narrative fiction drawing from his experiences. That has since translated into a successful literary career; his award-winning 1999 debut novel Brixton Rock was adapted for the stage and as a short film, and in 2008, he received an MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list for services to literature. But he hasn’t always felt welcomed by the literary establishment. “I make no apologies for writing about hustlers, or people like me who loved reggae back in the day,” he says, adding that for the first 13 or so years of his career, he was never invited to any major literary festival, even though he was producing what he felt to be good work that was receiving positive reviews. “There was an attitude that [my work] was only for Black people of a certain demographic. I like to counter that, because I think they’re universal stories with universal themes: the themes of belonging, of having a country not accept you, of racism.”

Looking back now, Wheatle hopes McQueen’s film “places value on lives similar to mine, who feel that they don’t belong, that they’re not being listened to, that they can’t achieve anything.” Wheatle has been to Jamaica many times, and has often found himself wondering whether he would have become the writer he is today had he grown up there. “Even though I suffered so much here, at least I had the opportunity to become what I am today,” he says. “I’m not going to try to sugarcoat it: life is, at times, very unfair. But what opportunities we have, we have to latch onto. However slim the opportunity is, we have to take it, and try to realize that potential with it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com