In a scene in the new film Red, White and Blue, the third installment of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe anthology, a young Leroy Logan attends his first day of police training in 1980s London. The officer-in-training, played by John Boyega, introduces himself to the rest of the cohort: “One thing I will say outright, I’m not here to make any friends. I’m here to bring change to this organization from the inside out.”

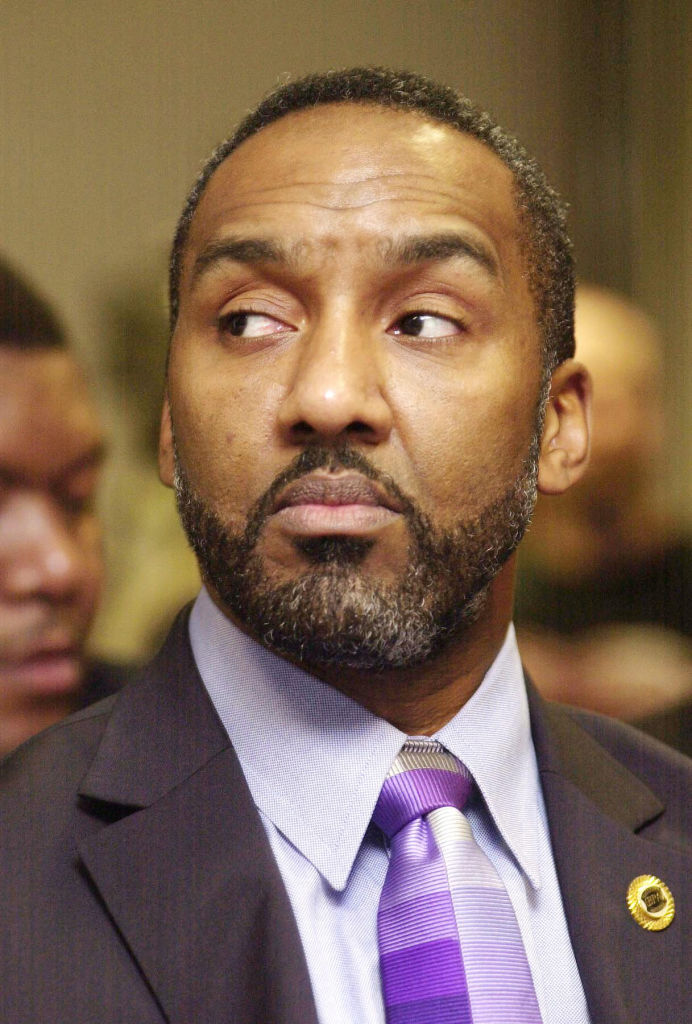

The character is based on a real-life officer of the same name, and this quote reflects the philosophy that informed his career. “I entered clearly knowing that I am a Black man who happened to be a cop,” he tells TIME, reflecting on joining the force at age 26. “I did not go into the organization to assimilate and adopt the norms and values of the organization.” Now 63, Logan is one of several inspirations for the Oscar-winning McQueen’s new anthology, five films that tells stories about the West Indian community in London. Red, White and Blue shows Logan’s own experiences with policing, the decision he made to switch careers and join the force, and the tensions that his decision threw up in the workplace, his family and community. Logan would later be elected as the first chair of the National Black Police Association in 1998, receive a Member of the British Empire award from Queen Elizabeth in 2000, and later retire in 2013 after 30 years in the force.

For McQueen, Logan’s story offers a different perspective on Black British resistance, particularly when compared to the 1970 trial of the Mangrove Nine, dramatized in Small Axe’s first installment Mangrove, which marked the first judicial acknowledgment that there was “evidence of racial hatred” in London’s Metropolitan police force. The concept for Red, White and Blue emerged from the Small Axe writers’ room McQueen had gathered. “I love the idea of the establishment, and someone trying to enter it,” the filmmaker told TIME in a recent interview. “What Leroy’s story says is that it’s do or die, really.”

How Logan switched careers from science to law enforcement

When Logan and McQueen met in 2016, Logan felt the director had understood his story. Logan recalls their conversations, with McQueen asking him why he left his “first love,” the field of science, for his “worst nightmare,” the police force. “At the time, it actually didn’t make sense to me,” says Logan. “I really did question my sanity for the first 10 years.”

Born in north London in 1957, Logan spent part of his childhood in Jamaica, where his parents had emigrated from as part of the Windrush generation. It was there that he saw more Black people in authority roles like police officers. Back in the U.K. when he was pursuing his degree, he remembered seeing a Black police officer on patrol, and the image stayed with him. Off-duty police officers shared the sports facilities he used while working as a scientist at the Royal Free Hospital. Through them, he says he was introduced to a more human side of the police force that his community had come to distrust.

After going on drives with the officers he met at the gym, and becoming more convinced that his presence could help change racist attitudes from within, Logan left a career in forensic science to join the police in 1983. “Casual racism was terrible,” he says. He recalls having the N word written across his locker at work, as depicted in the film. “You sort of felt, well, no wonder people don’t join the organization. It was a hostile environment. But I realized I just had to stand strong. I wasn’t going to let them grind me down.”

‘I was between a rock and a hard place’

Logan joined amid a recruitment drive to attract more Black officers and officers of color, given the fraught nature of race relations in Britain at the time. In 1981 and 1985, major riots broke out in cities across the country, in explosions of longstanding simmering tensions between local communities and police forces, who were disproportionately using “stop and search” powers against young Black men. (The 1981 riots in Brixton are depicted in another film in the Small Axe series, Alex Wheatle.) In 1983, the same year Logan joined the force, a report commissioned by the London Metropolitan Police concluded that racial prejudice was pervasive within the Metropolitan Police, and relations with young West Indians were “disastrous.”

Logan and his family had personal experience with heavy-handed policing in their community. Just after Logan submitted his application to join the police, his father Kenneth, a truck driver, was arrested on the street over a traffic matter and sustained facial injuries after two officers assaulted him. “I thought, well I have to put that [a career in the police] to one side, I’m not going to do it,” says Logan. But he stayed the course. “There was a sense of purpose, and I felt it was something I had to pursue, and if I didn’t, I would be in more torment.”

Despite Kenneth’s reservations, he was supportive of his son. That aspect, too, interested McQueen. “As well as being in an environment which wasn’t particularly welcoming, it’s also about trying to grapple with your own parents’ wants and needs,” the director says. Beyond the pushback from his family and colleagues, Logan also experienced new tensions with his community, as he was seen as a traitor for joining the force that had discriminated against them. “I was between a rock and a hard place,” he says.

The context of today’s Black Lives Matter movement

Although McQueen thought about an early concept for Small Axe 11 years ago, the release of the series comes during a year when the Black Lives Matter movement, and in particular unchecked police violence against Black people, has received renewed international attention. Logan believes the same prejudices that existed when he was an officer still need to be unlearned. “What happened to George Floyd, and the sadness I felt when that officer lynched him…we had the same oath to protect and serve, and it saddened me greatly.”

In the U.K., he feels the situation has regressed at least 20 years when it comes to heavy-handed enforcement tactics and a return to stop and search. Official figures this year indicated that Black people are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched by police officers than white people across England and Wales, and that the use of stop and search powers is at a six-year high. Logan is involved in several social justice projects, and says that the young people he works with through the charity Voyage Youth have spoken about feeling over-policed and underprotected, and how the protector and the predator wear the same uniform. “For me, that’s a real indictment of where policing has gone terribly wrong,” Logan says. “Trust and confidence is the worst it’s been in decades.”

Boyega voiced the frustrations of many in the Black community in the wake of George Floyd’s death, telling crowds at a Black Lives Matter protest in London in June that “at least you understand how painful it is to be reminded every day that your race means nothing.” The protest took place before shooting on Red, White and Blue wrapped, and McQueen says Boyega definitely had an impression on the project after that speech. Speaking in a recent interview with Variety, Boyega reflected on portraying Logan: “This is essentially a character study into a man who goes through a system that wasn’t ready for him…I definitely think I’m part of the generation that benefited from a lot of his work in the community, especially youth groups.”

To see Boyega portray him onscreen has been cathartic for Logan, and he hopes that it will be the source of conversations, particularly for schoolchildren who can see a part of Black British history represented in film. And although he’s retired from the force, he still wants to challenge the institutional racism he sees within it. “I know the ingredients are there to resolve everything about it,” he says, reflecting on his senior role in policing the London 2012 Olympics. “It just needs the right leadership and the right attitude to get that accountability and transparency that’s necessary.” Since helping to found the Black Police Association in 1994, Logan says he’s been determined to keep going. “If that’s my legacy, if it reads on my cremation plaque he gave it his best shot, he didn’t give up, that’s important for me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com