Eight months after the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic, COVID-19 is reaching the last places on Earth that remained untouched by the coronavirus.

On Wednesday, Vanuatu, a Pacific island nation about 1,200 miles northeast of Australia, reported its first COVID-19 case. Two other countries in the Pacific Ocean, the Marshall Islands and Solomon Islands, reported their first infections in October. In Samoa, workers who serviced a ship with COVID-19-positive crew members are in quarantine.

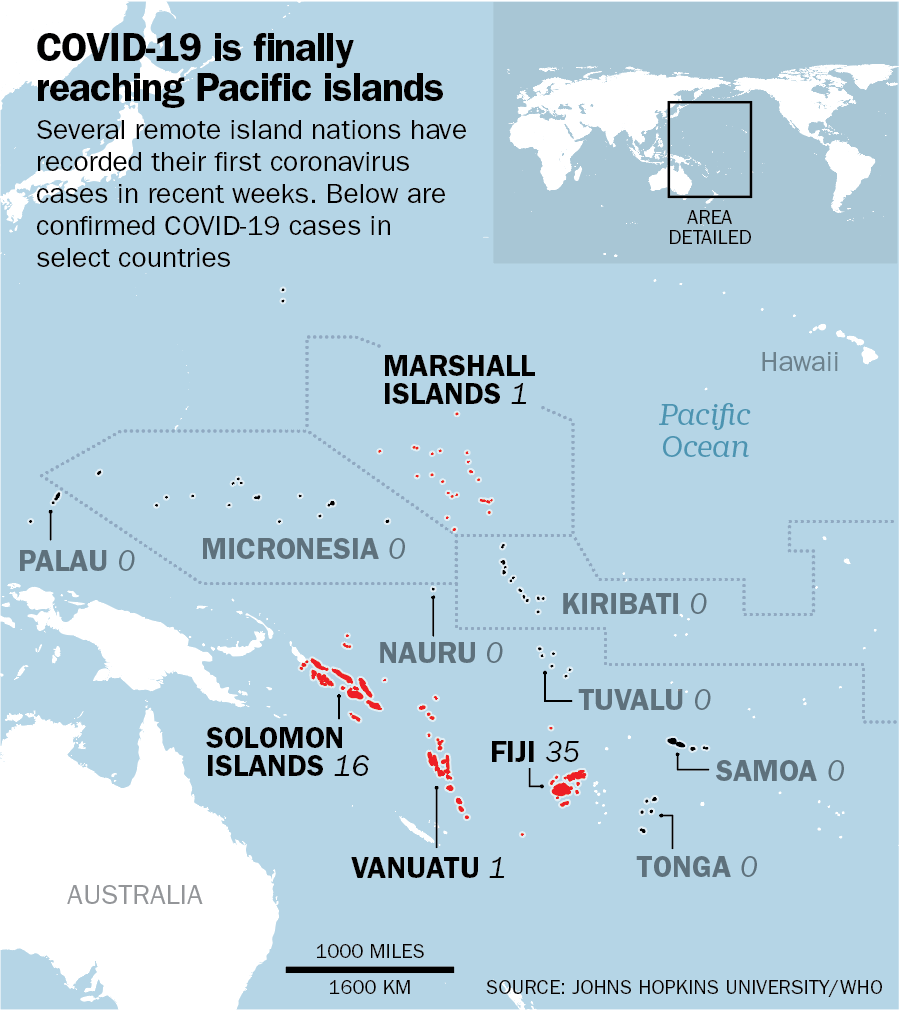

By most estimates, just nine countries have not yet reported any COVID-19 cases. Except for North Korea and Turkmenistan, where experts say COVID-19 likely exists, all of them are far-flung Pacific island nations—Kiribati, the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Samoa.

Most Pacific island countries closed their borders early in the COVID-19 outbreak. But as infections surge around the globe, with cases surpassing 50 million, the coronavirus is beginning to creep in.

In Vanuatu, the health department said a 23-year-old man who had recently returned from the United States was confirmed to have the virus after being tested while in quarantine. In response to the COVID-19 case, the government has suspended transport in and out of its capital city Port Vila and has launched an operation to trace and test everyone the man may have come into contact with.

Vanuatu, which is made of some 80 islands stretching across 800 miles of the South Pacific Ocean, closed its borders in March to keep the virus from entering. It even banned foreign aid workers from entering the country after a Category 5 storm devastated the country in April. But it has allowed Vanuatu residents and citizens overseas to return home.

Read more: Tracking the Spread of the Coronavirus Outbreak Around the World

The Marshall Islands recorded its first cases in the last week of October in workers at a U.S. military base who had arrived from Hawaii. The Solomon Islands also recorded its first case in early October; the remote island chain has since confirmed more than a dozen cases among arrivals in quarantine. Neither have yet recorded community transmission of the virus, and this week the Marshall Islands declared itself COVID-19 free again.

In Samoa, three crew members on board a ship that stopped in port have tested positive for the virus in recent days; workers who serviced the ship are now in isolation.

Many Pacific islands ‘can’t cope with even a few cases of COVID-19’

The good news is that, because COVID-19 took so long to get there, these Pacific nations had time to prepare—and may be able to stop the virus from spreading through their populations.

Lana Elliott, an expert on public health in the Pacific at the Queensland University of Technology, is hopeful that Vanautu’s first case can be contained. She says that not having a COVID-19 case until this week has bought the country of some 300,000 people crucial time.

The government and the ministry of health, she says, have “worked diligently for the last number of months to prepare for this exact situation. Processes are in place to ensure this patient can be treated and that the threat to health workers and the broader population is managed.”

There is reason for concern about Vanuatu’s ability to handle a COVID-19 outbreak, should the virus begin spreading in the community.

“Vanuatu, like many of the small islands in the Pacific, can’t cope with even a few cases of COVID-19,” says Colin Tukuitonga, an associate dean at the University of Auckland medical school and the former chief executive of New Zealand’s Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs. “A handful of cases on a small island is going to overwhelm the health system; these are very small and not well funded health systems. They often lack critical equipment, the critical skills,” he says.

As a result, contact tracing capabilities are of the utmost importance in preventing community transmission. “That’s the test. How quickly and how reliably the local authorities can identify the contacts,” he says. “It’s not an easy job.”

And unlike many countries in the Asia-Pacific that have used apps to trace contacts, no such technology is available in Vanuatu, he says, which will make the contact tracing process more challenging.

Vanuatu’s director of public health, Len Tarivonda, said that around 200 people had been identified as potential contacts of the infected man, including airline, customs and hotel staff, all of whom are now undergoing testing.

“We are concerned about that, especially since the staff who were working at the borders or the airline, they would have gone back to their families since last week,” Tarivonda told an Australian Broadcasting Corporation radio program.

Dan McGarry, an independent journalist who has lived in Vanuatu for more than 17 years, tells TIME that the news has sparked some fear in Vanuatu, and some are buying face masks to prepare for a possible outbreak. But most people have confidence that the illness is still contained, he says.

“We’re vulnerable and we know it. Our health care services have never been great, and intensive care simply doesn’t exist. We don’t have respirators, and we have very limited critical care facilities. If this were to reach the outer islands, people there would have next to no health care services available to them.”

Margaret Kenning, who lives on a small island in Vanuatu called Nguna says that her neighbors gathered to listen to the midday news on a transistor radio on Wednesday to hear how the government planned to deal with the first COVID-19 case.

The island hasn’t been spared the impacts of COVID-19

Although Vanuatu has managed to fend off the coronavirus until this week, it hasn’t been spared the economic hardship that the pandemic has caused all around the world. Tess Newton Cain, the project leader for the Pacific Hub at the Griffith Asia Institute, a research center, says that the Pacific islands—almost all of which have also closed their borders to keep COVID-19 out—have been hit hard economically. Vanuatu’s tourism-dependent economy is expected to decline 8.3% this year. Others have fared even worse. In Fiji, which has mostly been shut to tourism, GDP is expected dive more than 20% this year.

The journalist McGarry says despite a generous government bailout program in Vanuatu, unemployment is skyrocketing and foreclosures are mounting by the day. “We’re bending as far as we can, but things are starting to break,” he says.

While the closure of borders has “been extremely good for managing health impacts, it’s had quite devastating effect on the economy,” Newton Cain says. “There’s been a lot of job losses, a lot of tourism-focused businesses have closed or are working on really reduced hours.”

Still, Tukuitonga, the former New Zealand diplomat, says trying to keep the virus completely out of the country remains the right strategy for Vanuatu and many other countries in the Pacific.

“The primary aim of keeping it out or keeping it contained at the border is still the right one because if it gets into the community the islands will be simply overwhelmed,” he says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Amy Gunia at amy.gunia@time.com