Four weeks after my brother Ben’s funeral in 2009, the Army returned his belongings in carefully packed boxes, some still caked in sand and dust. In one was a black velvet bag with a black ribbon that contained the items he’d held in his pockets that day: an Altoid box that I had decorated and filled with family photos, and a poem by Brian Andreas that was read at our brother Sam’s wedding. He’d laminated the poem with Scotch tape, and though the edges were frayed and ripped, miraculously it was still legible.

Buried even deeper, between uniforms and Hanes T-shirts, was a single index card. On it, Ben had written, “To my little sister Annie. A little advice I’ve picked up over the years, from one traveler to another. ‘BARN’S BURNT DOWN… NOW I CAN SEE THE MOON – MASAHIDE.’” I had never seen that quote before, but I knew why he’d written it down for me, probably while lying on a dusty cot somewhere in Afghanistan. Ben was the eternal optimist, and I was the queen of catastrophizing. I had been sure he wouldn’t make it home from Afghanistan; maybe he knew I was right.

A hero in life, Ben was sainted in death. News outlets loved his story: a well-educated captain in the U.S. Army who had previously worked at the CDC and FEMA, and had started a nonprofit that provided clean water to villages in northern Uganda after his first deployment in the Horn of Africa. Our family was interviewed on NBC Nightly News, our dad’s favorite journalist wrote a piece on him for TIME magazine, and countless local newspapers plastered his face on the front page.

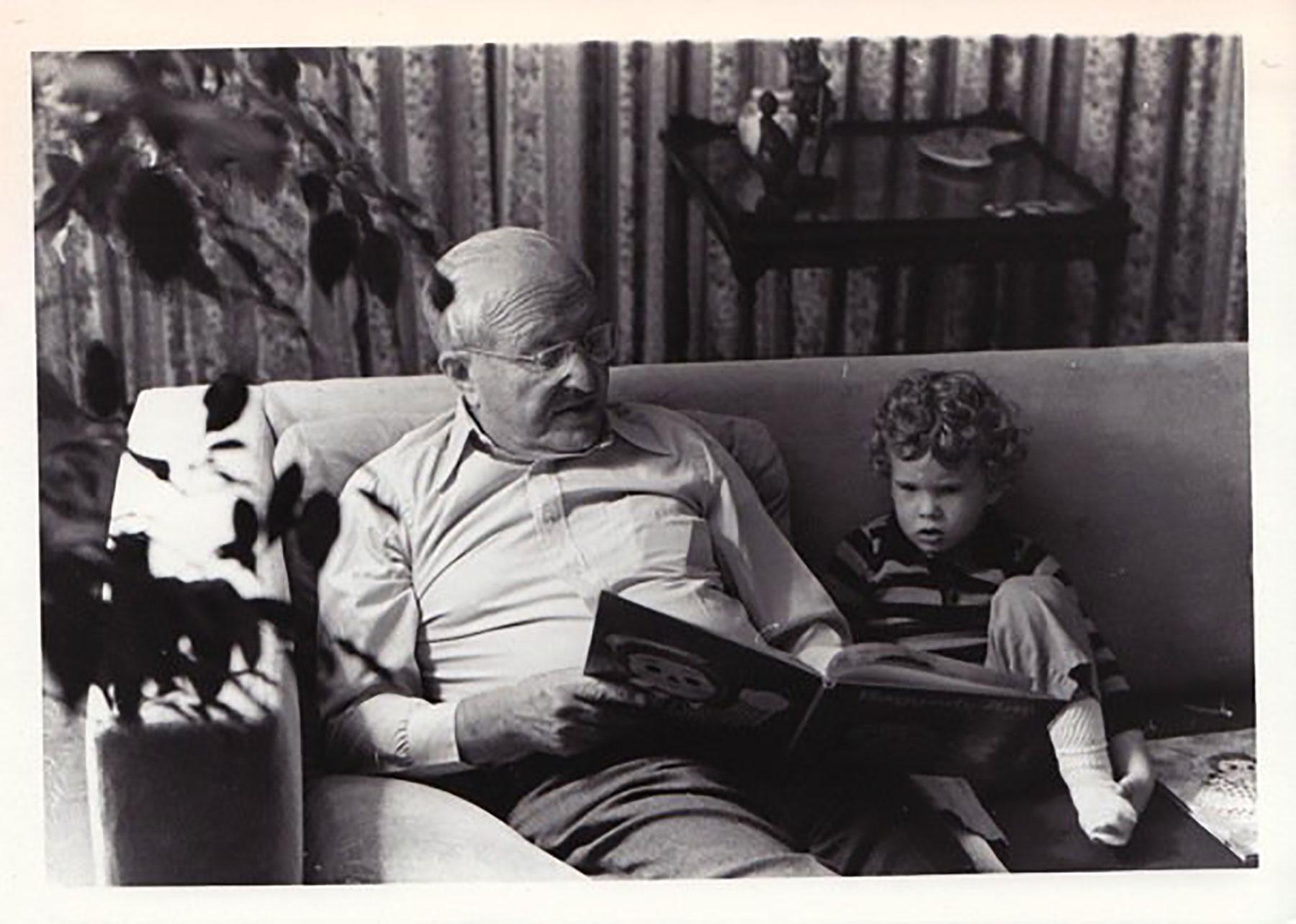

I was proud of his posthumous status; I always thought Ben was perfect and was glad the world agreed. Growing up, all I ever wanted was to be like my big brothers. I would introduce myself as “Ben and Sam’s little sister.” Who cared what my name was? All that mattered was that I was related to them.

When my parents moved out of our childhood home four years ago, we packed up Ben’s journals and letters, never opening a single one. Sam and I agreed that we needed to keep them safe should we ever decide to read them, but at the time, we weren’t ready.

Then as if Ben’s death weren’t enough, I began to lose the country he sacrificed his life for. He served under a commander in chief who believed in hope and change, but by 2019 our government was locking children in cages and had elected a sexual predator to the White House.

The further our country got from the ideals that Ben held so close, the more I was drawn to his diaries, convinced that they could help me regain my own faith in the humanity of others. I had them right there at my fingertips, but I was afraid to read them. Afraid that they might reveal a dark secret that I’d rather not know, that they’d ruin the perfect image I had of him, or worst of all, that they might reveal his disappointment in me.

During his first deployment I’d relocated to Colorado and lived as a ski bum for seven months before admitting that I hated skiing and moving back home. When he was killed, I was in grad school studying toy design. While he built hospitals, I built doll houses. What did he think of me? Was I forever a selfish child? Was I worthy of his love?

As the world continued to crumble around me, the ashes grew taller than the moon. The COVID-19 pandemic hit and my husband and I left Brooklyn with our two young children and headed to my parents’ home in Connecticut to quarantine there. In a desperate attempt to dig myself out, I collected all of Ben’s letters and diaries and spread them out on bed in front of me. I picked up a journal he’d kept with him in Afghanistan and flipped to a random page.

I had no idea he’d been so scared. How did I not know he’d been so scared?

Currently lying on the floor of a vacant school we’ve occupied along with the Afghan Army in a village north of Kulak. First chance we’ve had to rest in at least 72 hours. Left Kandahar Friday just after midnight and drove slowly north until around 5am. Then dismounted and patrolled for 10 hours into Kuhak. It was the 2nd time since we’ve been here that I expected to be attacked on a patrol. Looking for landmines and IED’s – said the Sh’ma and Barechu under my breath as we crossed danger areas.

I was immediately transported back in time to the months he was deployed when I would lie awake, convinced of the worst but he would always call home and tell us he was safe. I had no idea he’d been so scared. How did I not know he’d been so scared?

On October 2, 2009, while on one of the very missions he’d described, a suicide bomber waited silently behind a building as Ben rounded the corner and took my brother’s life. I’ll never know if he was saying the Sh’ma, the prayer a Jewish person is supposed to say before death, under his breath as the blast struck.

As Ben’s body was being transported back to the base and placed in a casket, I was designing a new preschool toy. When my father returned home from work and found two soldiers on his front porch, I was walking to Sam’s apartment to babysit his son. While my dad was telling my mom that their firstborn child was gone, I was putting my nephew to sleep. When our parents called Sam to tell him the news, I was trying to decide if I should order BBQ or sushi for dinner. When Sam hugged me tight and told me the news, I collapsed.

As painful as they were, the memories that were triggered by seeing his distinct, looping handwriting were addicting. I begged Ben’s forgiveness for intruding into his personal thoughts and picked up another diary.

2/6/98 Geneva, Switzerland

Went to the Red Cross Museum today and got a needed reminder of the faces behind war. Not the numbers we talk about, but the faces. It should be a museum that’s mandatory for everyone in Geneva, and it made me wonder: Why don’t people learn war kills? Can this be changed? Is war human nature? No. Human nature is a desire for security, food, and shelter. So does a solution exist? Help. Seems like the only choice for now. Just go in and help. I’ll come back to this more later.

I wanted to go back in time and scream at the 21-year-old writing those words. Yes, Ben. War kills. It will kill you. But I know it wouldn’t have done any good. He needed to help like he needed to breathe. Nothing we said would have talked him out of it. And so I kept reading.

9/20/99 Arlington, VA

So where am I going to make my mark? The Journal of a Frustrated, Inspired Idealist Without the Intelligence to Reach His Desired, Inspired Potential.

Well that was raw and honest.

The setup of life is so much fun, so frustrating, so much to learn about myself and about how to tackle life everywhere I go.

In these pages he stepped off his posthumous pedestal and became real to me again. I rediscovered the big brother who used to call me for advice about girls when he was in college (I was 12) and would come home for the weekend so I could take him clothes shopping. There he was. The human who explored life, questioned his purpose and quoted Indigo Girls on nearly every page.

8/22/00

Grandma Goldie made a difference that endures 100 years later. She came to America, stowed away on a boat, and her choice – her initiative, bravery, intelligence, led to Grandpa, who saved I don’t know how many lives in WWII and Waterbury, then to Allen, Neal, Gary, and Jeff, then myself, Sam, Annie, all the cousins who have, I believe, made the world a better place. So Great Grandma Goldie made a difference in 100 years. What will I do?

Ben made a difference. We will learn and grow from his life just as we will from every soldier who has perished on the battlefield, every soul lost to COVID-19, and every innocent casualty of the Trump Administration. They will not be buried in the ash.

For the first time since Ben’s death, I will spend this Veterans Day blanketed in the glow of the moon with my brother by my side. I’ve learned that we can mourn the crumbling world while still keeping our chins held high, ready to fight and face the new world that lies ahead.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com