In the 20th century, alphabetical order appeared to be immortal. No longer could anyone at home in an alphabetic writing system remember a time when the automatic response to ordering had not been alphabetical. In fact, it often seemed that the chaos and fecundity of the world could be tamed by the power of alphabetization alone.

Paul Otlet (1868–1944) was a Belgian visionary who wanted to—and believed he could—categorize all the information in the world. Anything ever written in a book, everything ever known, could be compressed, he believed, into a card system: one nugget of knowledge per index card, all filed in alphabetical order, whence any information about anything, anyone, anywhere, at any time, could be retrieved. Otlet began modestly in the 1890s, creating a bibliography of sociological literature. He then spread his wings to found the International Institute of Bibliography in Brussels, which drew on as many library catalogues and bibliographies as could be consulted to compile a summary, and summation, he hoped, of all libraries and all books: “an inventory of all that has been written at all times, in all languages, and on all subjects.” Otlet then established a subscription service that supplied his customers monthly with standardized cards filled with newly précised information. By 1900 he had 300 full members, and by the outbreak of the First World War another 1,500 people annually were approaching the Institute for information.

The Second World War saw utopian dreams wane, to be replaced by pragmatism. In Germany in 1940, the government ordered the seizure of any books from across occupied Europe that might contribute to the stock of the projected library of the Nazi Hohe Schule, or University of the Third Reich. But Otlet’s Universal Bibliography, comprising nearly fifteen million cards after almost half a century of indexing and summarizing, was spurned: “It is an impossible mess,” it was reported back to headquarters, “and [it is] high time for this all to be cleared away.” Nevertheless, there were elements that the Nazis thought worth preserving: “The card catalogue might prove rather useful.” This sounds harsh, and must have been unbearable for the elderly Otlet, but in retrospect it is worth noting that it was the card catalogue, the engine of his system, that was deemed worthy of preservation.

For in the preceding half century, alphabetical systems had spread everywhere. Even when the great medieval encyclopedists were aware of alphabetical order, they had frequently disdained it. By contrast, at the start of the 20th century Nelson’s Encyclopedia (1909), soon to be retitled Nelson’s Perpetual Looseleaf Encyclopedia, had leapt on alphabetization as its savior in an attempt to find a solution to the bane of encyclopedists of all eras, that of becoming out of date. Nelson’s volumes consisted of pages of alphabetically ordered entries, like any other modern encyclopedia. The difference was that those pages were not permanently bound into their covers as regular books were, but manufactured as a loose-leaf system and held in place with pins in the binding that opened with a special key. Nelson’s was “a modern book,” trumpeted the publisher’s preface, with “a new and special emphasis . . . on subjects which are of wide and active interest to-day”: namely, the sciences and technology, as well as biographical essays on living people, all of which needed regular updating. Each volume included “Our Guarantee”: “no less than 500 removable pages” would be sent “without further cost to each subscriber” for at least three years after purchase. As has now become unsurprising, however, and despite their very product hinging on alphabetization, and it being its main selling point, the system itself was apparently invisible even to Nelson’s: the encyclopedia contained an entry for “Alphabet,” covering the history of writing, but none for “alphabetization.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

It might well be that alphabetical order, even in a perpetually updated reference work, had by 1909 become invisible because it was so routine and so ordinary, just as it had in that other beacon of alphabetical order, the telephone directory, or phone book. Street guides, and later post office directories, precursors to phone books, had appeared in the 18th and 19th centuries in many cities. These publications listed the names, occupations, and addresses of residents and businesses, arranged in alphabetical order or, occasionally, in street order that was itself organized alphabetically within districts. Even so, most of these early directories had included prominent analphabetical components: for instance, they were prefaced by registers of government officials, magistrates, aldermen, or other civic leaders or institutions, almost all of whom were listed hierarchically or chronologically.

The first telephones were sold in pairs, the owner of one of a pair able to communicate only with the owner of the other. Customers therefore had no need for directories. In 1878 George Coy, who had earlier worked for a telegraph company in Connecticut, designed and built a “switch board,” where calls could be “switched” from one exchange to another, vastly increasing the reach of any one subscriber, who was now no longer tied solely to a single exchange. These switchboards housed a series of jacks, one per subscriber. When a subscriber rang through to the exchange, the operator answered, the caller asked for a fellow subscriber, and the operator plugged the caller’s jack into that linked to the requested subscriber.

Coy signed up 21 subscribers to his switchboard service in his first year. There was, of course, no need for numbers to be associated with each name: a subscriber would call the exchange and ask to speak to another subscriber by name or occupation: “Put me through to the post office,” or “Mr. Smith, please.” Within a few years, Coy was employing four operators to connect two hundred subscribers across several switchboards, and his much-expanded list now appeared in alphabetical order.

By 1880, the first known printed list of telephone subscribers in Britain—in effect, the first phone book—had appeared. It had 407 subscribers, still with no numbers linked to the names. In one respect these early switchboard operators were very like the medieval monastery librarians: where they had oversight of a few dozen, or a hundred, units, be they manuscripts or phone subscribers, the individual in charge could remember their location; but once there were more, some form of finding tool became necessary. In general, the early phone books used a variety of systems. Some were arranged in the order subscribers had joined the exchange or by the date they had purchased their telephone. Others grouped entries by trade or profession.

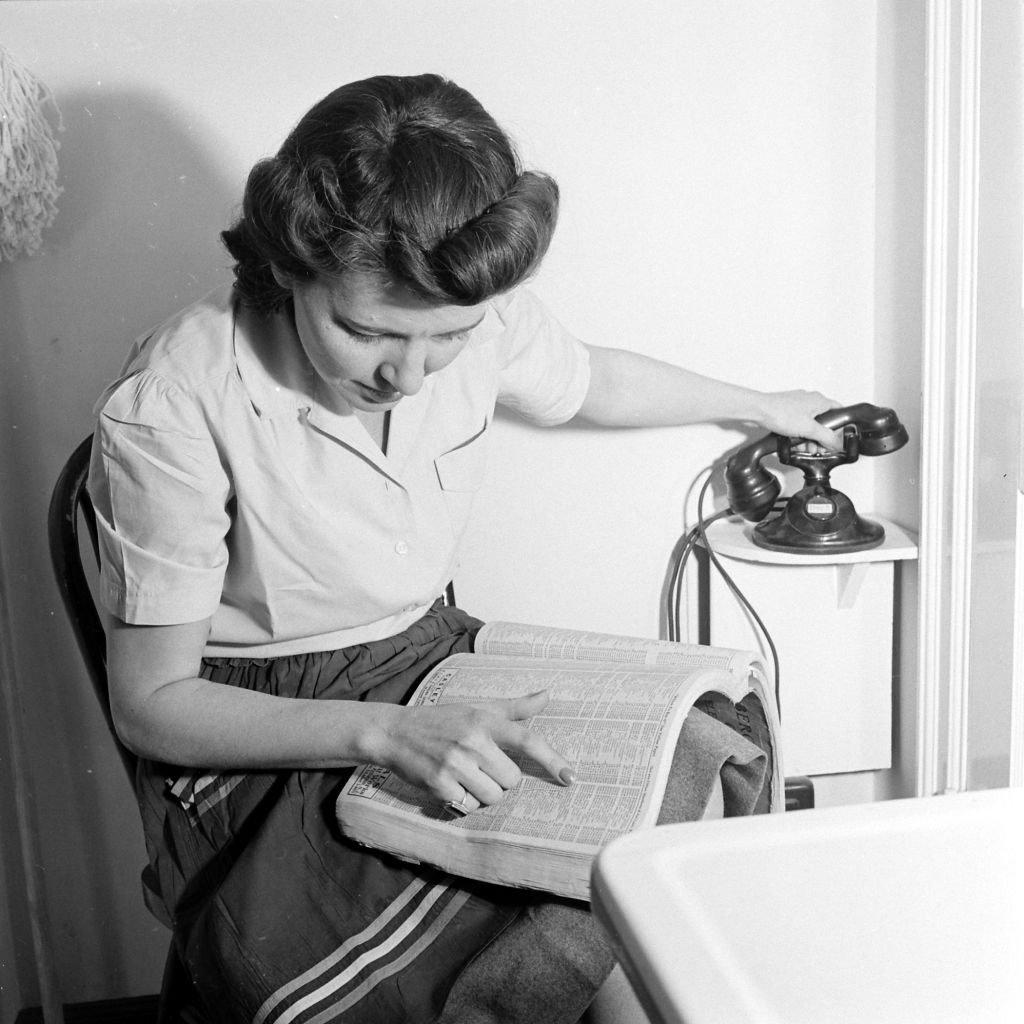

In the U.K., the telephone system came under the aegis of the post office, and by the 1960s directory corrections were the responsibility of one post office employee for every 56 phone book districts. These clerks used the current printed phone books as their starting point, making corrections in the margins, writing in new listings and removing numbers no longer in use, then amending the alphabetical order of entries as necessary. However reluctantly, though, the post office was rethinking its system, considering the possibility of transferring corrections onto card indexes—“prepared on typewriters,” the head of the department charged with compiling the directories noted with a flourish of modernity.

This post office employee was also, unusually, profoundly aware of how invisible the work his staff undertook was, how the country as a whole relied on the accuracy of those alphabetical listings without ever giving them their due. When he was appointed to his job, he later recounted, he felt that he was insufficiently versed in matters alphabetical, much less in what the experts considered to be best alphabetical practices. He therefore left a message for the librarian of the British Museum, asking for a list of authorities to consult. By return, the library supplied him with a single phone number, that of the man they said was the foremost expert in the field—only for him to discover it was his own.

Excerpted from A PLACE FOR EVERYTHING: A Curious History of Alphabetical Orderby Judith Flanders. Copyright © 2020. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com