It didn’t take more than one day of virtual kindergarten for Ryan Greenberg’s 5-year-old daughter, Samantha, to break down in tears, begging to go back to regular school where she could see other kids face-to-face.

“I’ll wear two masks,” she told him.

But for Samantha, in Montclair, N.J., and for hundreds of thousands of other children across the country, school will continue to be remote for at least the first weeks of school due to the coronavirus pandemic.

And while this school year has posed new challenges for students of all ages, it’s proving especially challenging for children as young as 4 or 5 years old to sit in front of computer screens for hours each day, learning how to navigate websites and how to mute and unmute their microphones during virtual lessons. Viral videos have captured the patience and energy required of teachers to keep young students engaged.

Such obstacles could help explain why kindergarten enrollment has declined in many districts across the country this year. That may translate to less money for school districts, which often receive funding based on enrollment, and to long-term losses for children who miss out on a critical year of early education.

In 2018, 84% of 5-year-olds in the U.S. were enrolled in preschool or kindergarten, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But most states don’t require kindergarten attendance, making it possible for parents to opt out if they’re unable to help their child with remote learning this year or if they think the virtual offering is not as valuable as traditional kindergarten.

There are no national kindergarten enrollment numbers available for this school year yet, but several districts reporting sharp declines of kindergarteners are not seeing the same enrollment drops in other grades. The Los Angeles Unified School District, the second largest school system in the country, which began the school year with online-only instruction, has nearly 6,000 fewer kindergarteners enrolled this year, a decline of 14% compared to last year. “The biggest drops in kindergarten enrollment are generally in neighborhoods with the lowest household incomes,” Superintendent Austin Beutner said in a briefing on Aug. 31. “We suspect some of this is because families may lack the ability to provide full-time support at home for online learning, which is necessary for very young learners.”

Read more: As the School Year Approaches, Education May Become the Pandemic’s Latest Casualty

Eric Mackey, the state superintendent of education in Alabama, mentioned the same trend during a state Board of Education meeting on Sept. 10. “Anecdotal information we’re getting is that kindergarten numbers are way down because parents are just saying, ‘Rather than do whatever we have to do this year, we’ll just hold our kids back one year,'” he said. “Which causes us two concerns: One is when they bring those children in next year, do they want to bring them into kindergarten or do they want to skip kindergarten and just start first grade?”

Though official enrollment numbers have not yet been finalized in many places, other districts are reporting similar early figures. In Montgomery County Public Schools, the largest school district in Maryland, which will remain remote through January, kindergarten enrollment is down by 1,011 students, about 9% compared to last year. In Florida, kindergarten enrollment decreased by 12% in Miami-Dade County Public Schools and by almost 14%, or 1,976 students, in Broward County Public Schools, the largest enrollment decline of all grade levels. A spokesperson for Broward schools said the district is “working to attract kindergarten students and is hopeful more families will enroll their children once our District returns to in-person instruction.”

The San Diego Unified School District, which also started the school year virtually, reported on Friday that kindergarteners represent two-thirds of its enrollment decline this year, and it encouraged families to enroll their 5-year-olds now. “Those early grade-levels are critical times in the life of a student,” Superintendent Cindy Marten said in a statement. “They set a child up for success in later grades, not just academically, but socially and emotionally as well.”

Anecdotal information we're getting is that kindergarten numbers are way down because parents are saying, 'Rather than do whatever we have to do this year, we'll just hold our kids back one year.'

Jenna Conway, the chief school readiness officer for Virginia, is anticipating a 15% to 25% drop in kindergarten enrollment across the state this year, based on numbers reported by districts thus far, though official enrollment numbers won’t be available until the end of the month.

“Everybody’s asking, where are the kids?” she says. And the answer is not yet clear. Some families might be holding their child back a year, a practice known as “redshirting.” Some might be enrolling their children in private school. Some might be homeschooling. And others have placed their child in daycare. Conway says about half of the Virginia child care providers that reopened have reported taking in some school-aged children, with a mix of daycares expanding to offer a kindergarten program or supervising children who are enrolled remotely in a public kindergarten.

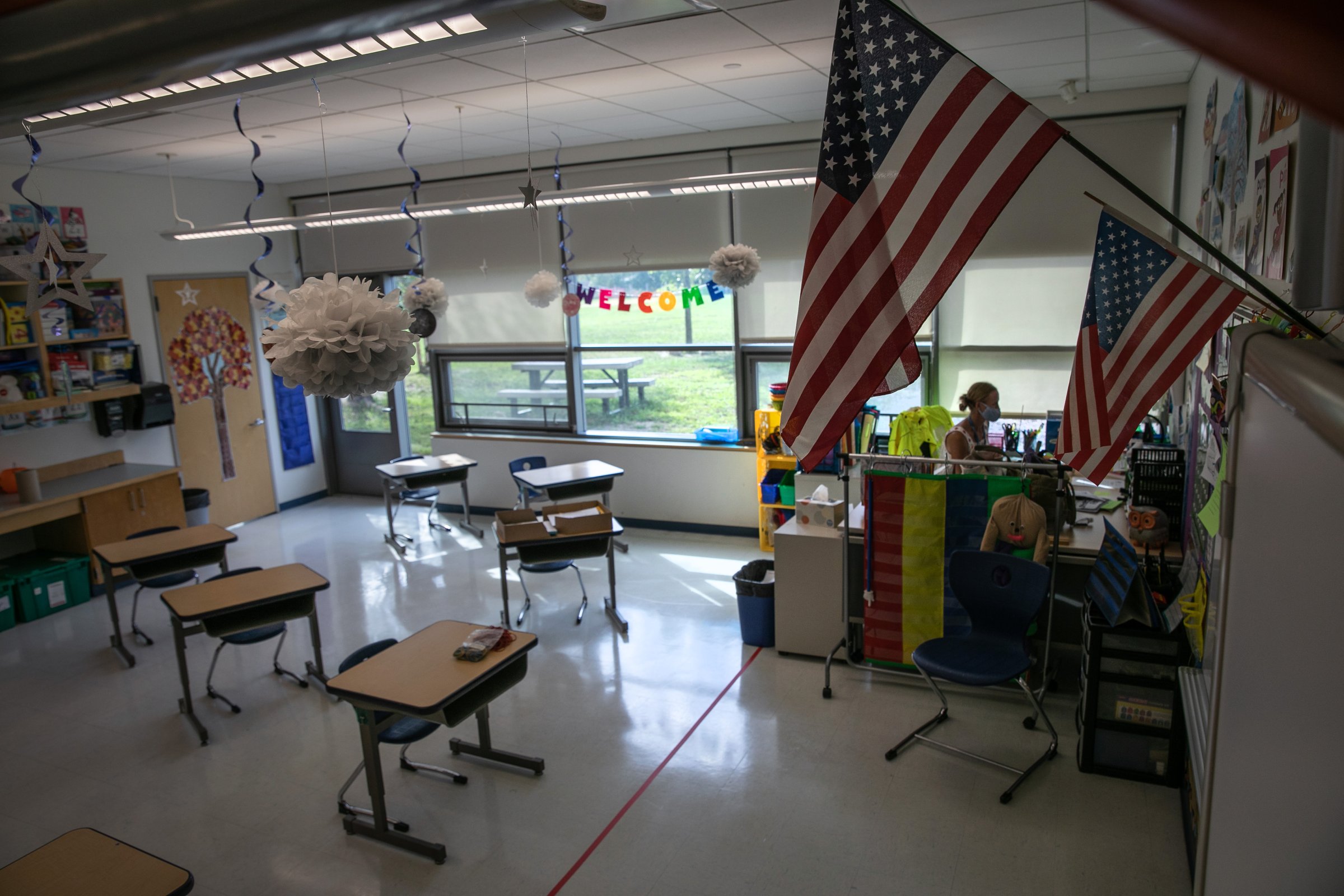

Nearly half of school districts across the country have reopened for fully in-person instruction, according to an analysis in late August by the Center on Reinventing Public Education. But 26% of districts, including many of the country’s largest school systems, have started the year fully remote. In recognition of the challenges facing the youngest learners, some districts have prioritized bringing kindergarteners and elementary schoolers back face-to-face first, before phasing in other grades.

“One of the biggest challenges is going to be the variability of experiences,” Conway says, noting that students in some districts will receive in-person instruction, while others remain fully remote, and that kids in affluent families will have the opportunity to learn just as much as they would in a typical school year, while many other children will fall further behind. She says policymakers and education leaders will have to rethink early education and kindergarten and provide additional support to students who don’t have the full-time help of a caregiver, a quiet place to learn or consistent Internet access.

“The hardest part about virtual kindergarten and pre-K is that the kids cannot do it on their own. They just can’t. I’ve both been able to observe classrooms and, downstairs in my house, observe my own child, and you know, there’s a lot of parents and caregivers in the frame,” Conway says. “Where are the places where parents aren’t able to support that? Where are the places where kids kind of go missing, either they’re absent or don’t log in?”

‘A lifetime of trying to catch up’

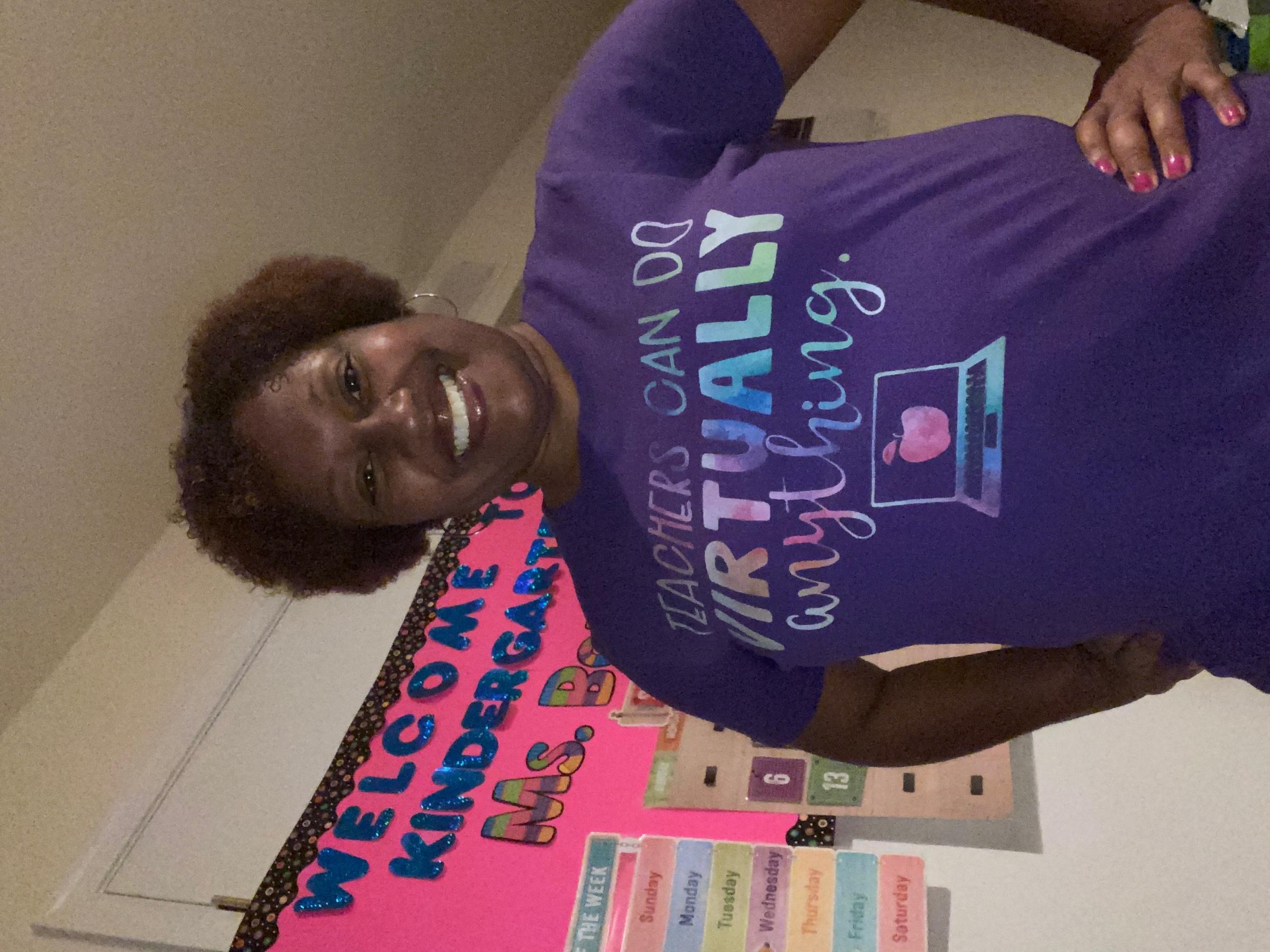

Traneisha Sanford, a kindergarten teacher at Sims Elementary School in Conyers, Ga., which is continuing with virtual learning through the first semester, says she has 13 students in her class this year, down from about 23 in a typical year. She turned her guest bedroom into a remote classroom, decorating it with bookshelves, posters and a colorful bulletin board that says, “Our kinder class is virtually the best,” in neon letters.

She starts each day by asking students to give her a thumbs-up or thumbs-down based on how they’re feeling. They sing alphabet songs, count to 100, decorate letters cut from construction paper and take “brain breaks” in between lessons.

“It’s not easy, but I’m very dedicated to my craft and my career. I am doing the best I can and making it work, but this is not an easy task at all for us teachers as well as the kids,” she says. “My fingers are crossed that we are able to go back inside our buildings, if we can, in January.”

Vatesha Bouler, a kindergarten teacher at Barack Obama Elementary School in Upper Marlboro, Md., who just began her 21st year as an educator, says she spent the first week of virtual school teaching students how to mute and unmute their microphones and turn their videos on and off, in between lessons about letter sounds, shapes and cooperation. Behind her desk at home, she hung up a list of distance learning rules, reminding students to “stay in one place” and “keep your sound on mute until you are asked to speak.”

“It takes a lot more work, a lot more patience, a lot more planning to teach not only kindergarten, but in my opinion, any grade level with distance learning versus being in the classroom,” she says. “I tell parents this is a learning experience for all of us. We are all holding each other’s hand during this.”

But some parents have found it overwhelming to juggle working and supervising virtual kindergarten. Jacquelyn Allsopp, who has three children, is considering unenrolling her 5-year-old from kindergarten in the South Orange-Maplewood School District in New Jersey after two weeks of remote learning, during which her daughter has grown restless and bored by hours in front of the computer each day.

“She’s running away all the time, and it’s like, ‘Can you please come back and look at the screen?’ She’s like, ‘Mommy, I don’t want to learn like this,'” Allsopp says. “And I can’t force her to sit there. She’s 5.”

Allsopp wrote to district leaders, raising concerns about whether four to six hours of screen time was age-appropriate for 5-year-olds. In a letter to families on Friday, the school district announced some changes for the youngest grades, shifting to three hours of live virtual instruction each morning, and offering art, music and physical education classes asynchronously instead, allowing families to choose when to participate in them.

If she decides to unenroll her daughter, Allsopp says she would homeschool her this year and send her to first grade next year. “I feel sad that this is not really school for her. Children at this age should be learning through play, and so much of kindergarten is learning through play, socialization, learning how to get in line, how to do the morning meeting, how to do all these things in a classroom setting,” Allsopp says. “If you’re not learning that, how is this productive?”

The benefits of traditional kindergarten have been well-documented. “We have a lot of evidence that these early learning experiences matter a lot for kids, both in the short and the very long run, into adulthood really,” says Chloe Gibbs, an assistant economics professor at the University of Notre Dame who has researched the impact of kindergarten, noting that quality kindergarten and pre-K can affect a child’s future educational attainment and earnings.

And the stakes of missing or delaying kindergarten are higher for children who would most benefit from an early-education boost, including children from low-income households or children who are learning English. “That delay could be really costly for them because it could mean a lifetime of trying to catch up on developing those skills,” she says. “We worry that just further disadvantages the kids who would most benefit from having these early learning investments in school.”

Education experts agree that, while kindergarten provides an important academic foundation, it is also key to helping children develop social-emotional and behavior skills — how to interact with classmates, how to listen to a teacher, how to follow classroom rules — which is harder to replicate over a computer screen.

And while remote learning continues, some parents are trying to make up for that.

Greenberg, the father in Montclair, N.J., says a few parents from his daughter’s kindergarten class recently organized a small outing to a park, so their kids could play. He asked Samantha if she wanted to go meet some of her classmates. “On the computer?” she said. In a park, he told her, “and she lit up instantly.”

Wearing masks, the kids ran around in the park for two hours, he said: “It was probably the highlight of the week.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com