The Great Depression, McCarthy era and Vietnam War. In addition to being pivotal episodes in modern American history that fueled periods of great unrest, these events have something else in common: they all served as the catalyst for distinct trends in horror films.

Horror films have gone through many phases since 1896’s French short silent film La Manoir du Diable (The House of the Devil), by director George Méliès. From the monster movies of the Depression to the gory slashers of the Vietnam era to the “torture porn” of the aughts, popular fright flicks have long tapped into pop culture’s most urgent fears. And in the wake of the events of 2020, COVID-19 looks poised to become the next entry on the long list of historic horror inspirations.

This link between horror and history makes sense to experts. James Kendrick, a film and digital media professor at Baylor University who specializes in horror film, says the history of horror movies is inexorably wrapped up in history itself. “The horror genre has always been a highly socially attuned genre because it draws on what we’re afraid of, and what we’re afraid of changes from era to era,” he says. “Basic fears remain the same, but the specific elements of what we’re afraid of ebb and flow at different times.”

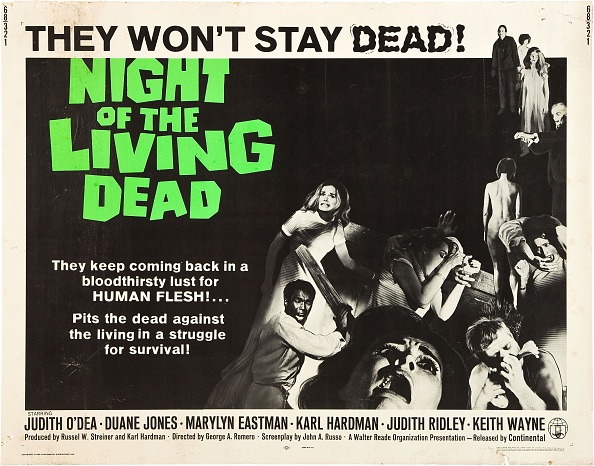

Of course, not every horror movie has a deeper meaning behind it. While Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980) successfully captured the popular zeitgeist, many of their sequels are largely box office cash grabs. But if you’re looking for a pivotal example of this phenomenon, look no further than writer-director George A. Romero’s seminal 1968 classic Night of the Living Dead.

Featuring the horror genre’s first Black lead (Duane Jones as Ben), Night of the Living Dead is a zombie movie that’s widely viewed as an allegorical critique of U.S. race relations in response to the political and social upheaval of the 1960s. But the film’s racial themes (arguably its most enduring subtext) weren’t part of the message that Romero said he originally intended to convey. “Our point was more the disintegration of society, the inability to communicate, disintegration of the family unit,” he said at a 2012 event hosted by the Toronto International Film Festival.

Romero’s claim that Night of the Living Dead‘s racial undertones weren’t intentional demonstrates how viewer interpretation can have as big an impact on a film’s legacy as whoever is behind the camera, says Kinitra Brooks, a literary studies professor at Michigan State University who specializes in horror. “Once you put your baby out in the world, other people are going to interpret and critique it. [Filmmakers] really don’t have control over that,” she says. “People are going to read things into your work of art.”

It’s easy to see how the horrors of 2020’s pandemic, from isolation to contagion, could not only prove a rich vein for filmmakers to draw on in coming years, but might also influence how audiences respond to future horror offerings. Let’s see how filmmakers might use COVID-19 to scare us in the months and years to come.

The Coronavirus Pandemic

With Rob Savage’s Host, a Zoom-based horror movie that was made entirely under coronavirus lockdown restrictions, debuting to rave reviews this summer, the realities of life amid a pandemic are already starting to influence the genre. Set within a Zoom call between a group of friends who decide to hold a remote seance, Host capitalizes on fears that might be triggered by extended isolation.

“Host isn’t a pandemic movie. Host is a lockdown thriller, very much about the specifics of being isolated, of being virtually together, but actually in a state of exposed isolation,” Savage told Slashfilm in August. “When push comes to shove, you’re on your own and your friends can only witness what’s happening to you. That was the fear we wanted to tap into.”

As far as sickness-related anxieties surrounding coronavirus go, Brooks says that the fear of contagion will likely remain a tried-and-true horror standby in coming years.

“I predict we’ll get some contagion films once the vaccine comes out,” she says. “Because that plays into the fear of science turning against us and making us something bad…Zombie horror fits in with contagion because there’s this idea that you’ll become one of a horde of zombies. You’ll lose the essence of who you are and then you’ll infect others.”

But the less tangible fears associated with the pandemic could also have a role to play in horror’s future, says Kendrick. “There are two things about coronavirus that really jump to my mind and the first is the notion of isolation—all the forced quarantining and people having to separate and not being able to engage in social activities. There have been some great horror films about isolation. It’s a theme that’s always sort of ripe.”

And the other? The idea of a loss of control, Kendrick says. “If you had told people 12 months ago that there was going to be this virus and it was going to bring the whole world to a stop and alter every facet of normal life, they would have brushed you off,” he says. “But the idea that there’s something out there that can spread and is, at the moment, beyond our science, beyond our social systems and beyond our ability to contain, is very scary.”

Think of dystopian thrillers like The Purge (2013), High-Rise (2015), 10 Cloverfield Lane (2016) and It Comes at Night (2017) that center on the breakdown of society as we know it for some examples of how this idea has previously manifested in horror cinema.

Whether these will be the main pandemic inspirations for future horror is yet to be seen, but all it takes is a quick look back through history to see how national emergencies have shaped the film genre.

The Great Depression

In the wake of the stock market crash of 1929 and the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world, monster movies that relied on supernatural elements to frighten viewers took off.

While silent horror flicks like Nosferatu (1922) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925) were already in play, with the introduction of sound to film, the 1930s became a golden age of horror. Audiences began flocking to theaters to watch monsters like Dracula (1930), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933) wreak havoc on unsuspecting victims.

By drawing on the fear of the unknown, filmmakers were able to provide moviegoers with a much-needed distraction from the everyday realities of the Depression, Brooks says. “People felt that [the challenges they were facing] were outside of their control,” she says. “And you want to blame someone. So a supernatural monster becomes the embodiment of the difficulties that you’re facing due to economic anxiety. It’s much easier to say, ‘Oh, it’s werewolves or Dracula or the Invisible Man. These supernatural things are the reason my life is so out of control,’ than to look at the economic policies that created [the situation].”

This emphasis on foreign horrors in faraway lands was also a reflection of the period of isolationism that America entered following World War I, says Kendrick. “In those early horror films, the horror is always something that’s out there. It’s always something that’s not part of mainstream life. It’s always this external horror,” he says. “Dracula is very clearly coded as Eastern European. In the Wolf Man, even though the main character, who’s ostensibly American, becomes a werewolf, he’s bitten by a ‘gypsy’ [as described in the movie]. So it’s like there’s this foreign contagion out there.”

The Atomic Age and McCarthyism

Whereas the horror movies of the ’30s served as a form of escapism for viewers, the fright flicks of the ’50s often brought rising fears of atomic power and communism to the forefront of their minds.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, science fiction-fueled creature features like Godzilla (1954), The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and Them! (1954) became all the rage. “There were all these movies where natural, harmless things would all of a sudden become large and great and a threat due to nuclear waste or an atom bomb dropping,” Brooks says.

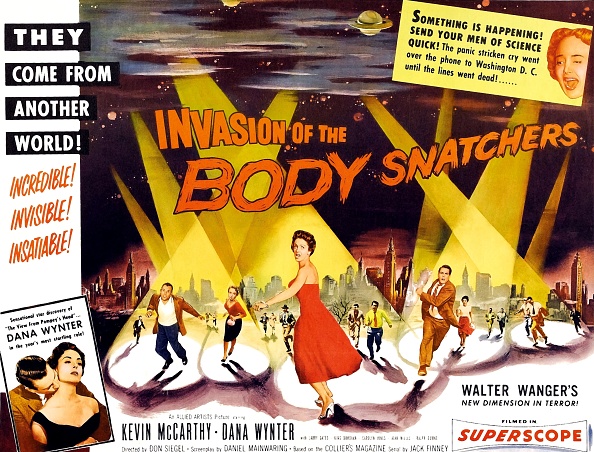

Simultaneously, as Cold War tensions escalated between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, McCarthy-era paranoia over communist infiltrators crept into horror in the form of movies about “body snatchers” and alien invaders. One film in particular that successfully captured this prevalent fear of the “red menace” was director Don Siegel’s 1956 classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers, says Kendrick.

“There was this fear of an invasion of some kind by an external force, which was always coded as the communists, the Soviets, the reds,” he says. “Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a really great example because it works as such a profound allegory for our fear of losing ourselves, of losing our minds to some kind of insidious influence.”

The Vietnam Era

In the midst of the dramatic political, social and cultural upheaval of the Vietnam era, scary movies that drew on the horrors of everyday life surged in popularity.

For some filmmakers, as demonstrated by movies like Psycho (1960), Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Exorcist (1973), that meant tapping into broad concerns over the rejection of traditional values and the unraveling of the nuclear family. In fact, the original Psycho, Kendrick says, completely changed the trajectory of the horror genre in that regard.

“Psycho was the first big, mainstream film that located horror squarely within the family,” he says. “In previous horror films, the family was the place of protection. Then you get to Psycho and all of a sudden, horror’s not this clearly coded vampire in a castle in Transylvania. It’s not a shambling monster. It’s not a werewolf. It’s not something obvious. It’s the relatively benign-looking guy behind the counter at the roadside motel who’s turned into a monster because of the perversions of his own mother. [Psycho] took horror from out there and put it squarely [within the realm of the family].”

Others recognized the visceral horrors of a war that was broadcast on the nightly news alongside reports of serial killers and crime sprees as the true nightmare fuel of the time. It was this sentiment that gave rise to the first wave of ultra-gory slasher flicks, including standouts like Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974).

“The genre certainly becomes a lot more visceral starting in the late ’60s. Night of the Living Dead moved that forward quite substantially,” Kendrick says. “Then you get into the slasher subgenre, which is centered on a seemingly unstoppable human psychopath. It was very much about the everyday. Look at Halloween, which is very purposefully set in this nondescript Midwestern town, or Friday the 13th, which takes place at a very common-looking summer camp. With A Nightmare on Elm Street, they put this idea of Elm Street as Main Street, U.S.A. in the title. [There was this sense of] you can’t get away from these things because they’re going to be wherever you are.”

The War on Terror and Cathartic Horror

Love it or hate it, the horror subgenre of “torture porn,” a term coined by New York Magazine film critic David Edelstein in 2006, ruled the first decade of the 21st century.

But while horror fans are divided over the merit of films like Saw (2004) and Hostel (2006) that traffic in unremitting sadistic violence and gruesome body horror, in a purely historical sense, Kendrick says that it was logical for them to have flourished in a post-9/11 world in which the war on terror cast the issue of torture into the public eye.

“Torture has been a fundamental element of horror films going all the way back,” he says. “But it’s curious that it reemerged in such a direct form in the post-9/11 era when there was so much talk about torture and whether it was necessary or unnecessary or ever justifiable. The genre was definitely going into darker, more visceral territory. So when you look at a movie like Hostel, which so clearly trades on that kind of imagery, even though you know it’s taking place in an Eastern European country, a lot of the visuals match up with what I think was the public mindset about what being caught by al-Qaeda and held in the Middle East would look like.”

The nature of these “torture porn” movies, Brooks says, could also have offered viewers a sense of catharsis in the midst of those uncertain times. “They can have a somewhat comical nature. Like, there’s all this s— going on in the world and you’re worried about this random dude kidnapping white teenagers and doing these crazy body horror things to them? Is that really the biggest threat right now? So there’s the fear, but I also think there’s the fun of how gory can you get, how far can you push this,” she says. “Remember, this is meant to be a catharsis. You’re supposed to see these things and go, ‘Whew, I’m glad that didn’t happen to me,’ and then keep it moving.”

The “Post-Racial Lie” and New Perspectives

In a 2017 interview with Vanity Fair, horror mastermind Jordan Peele referred to the Obama era, the period of time in which he wrote his groundbreaking 2017 film Get Out, as “the post-racial lie.”

“We were in this era where the calling out of racism was almost viewed as a step back,” he said. “Trump was saying that the first Black President wasn’t a citizen…There was this feeling like, ‘You know what, there’s a Black President. Maybe if we just step back, [Trump] can say his bullshit. No one cares. And racism will be gone.’ That’s the era I imagined this movie would come out in.”

Now, horror movies like Get Out that showcase perspectives outside of the white experience are rightfully getting their moment in the spotlight, says Brooks, referencing the genre’s historic centering of white males as the “ideal viewer.”

“Horror films are meant to explore the anxieties of the ideal viewer. Everyone else is tangential,” she says. “As we’re moving toward more contemporary types of horror, we’re seeing different folks’ anxieties on screen. Before, everyone else had to do the work to see things from the point of view of the ideal viewer. Now, [horror movies] are charging white viewers, and particularly white male viewers, with doing the work to understand different points of view and empathize with more people.”

A new wave of horror that gives voice to the lived experience of women has also produced a number of standout films over the past decade. From Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook (2014), in which a sinister presence torments a widowed mother and her young son, to David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2015), the story of a teenage girl’s terrifying battle with a sexually-transmitted curse, horror movies exploring fears and anxieties specific to womanhood are taking hold.

This year alone, women-made horror films like Romola Garai’s Amulet, Josephine Decker’s Shirley and Natalie Erika James’s Relic have added rich new layers to the ever-diversifying genre.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Megan McCluskey at megan.mccluskey@time.com