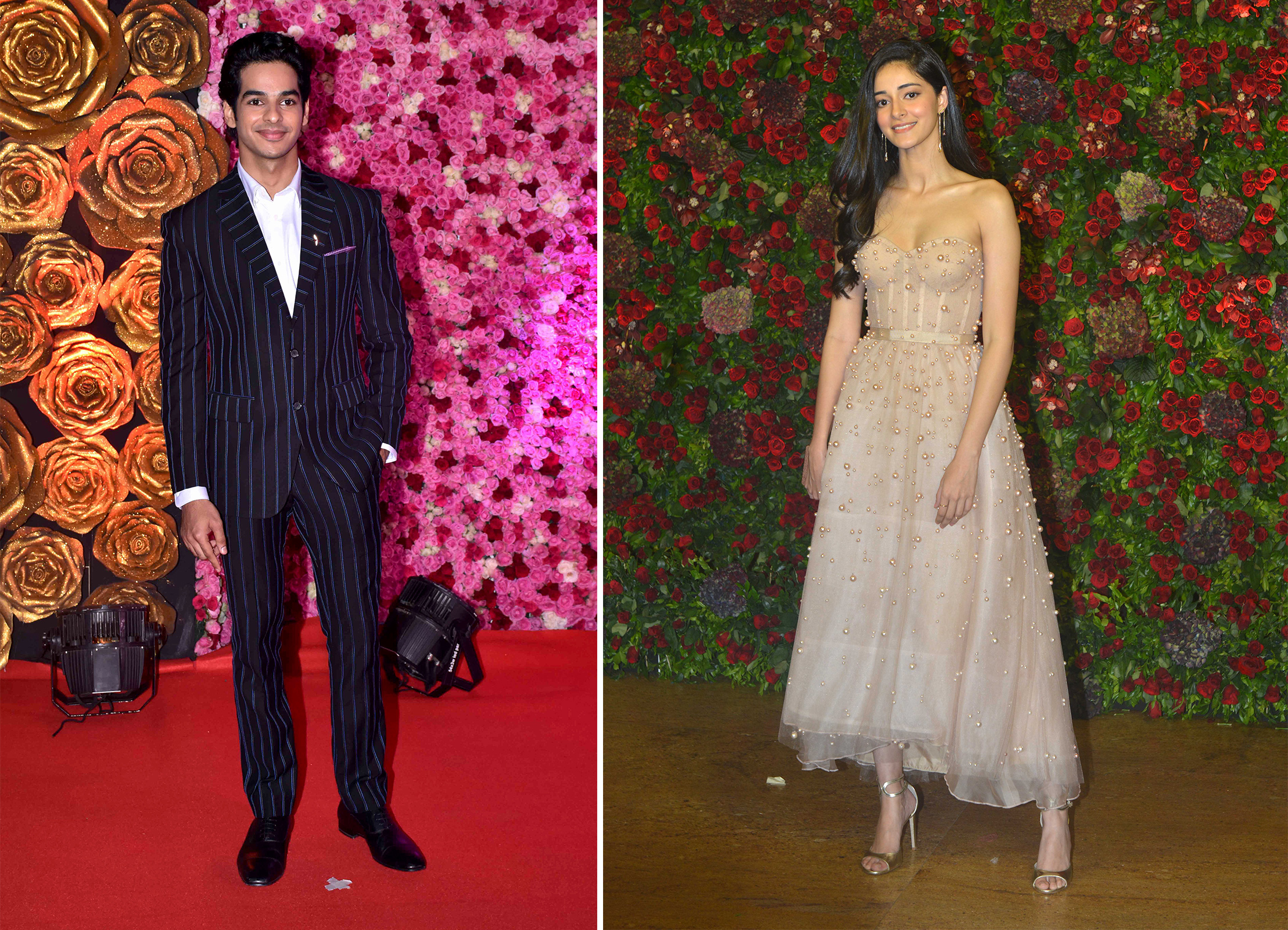

The upcoming Bollywood rom-com Khaali Peeli, starring actors Ishaan Khatter and Ananya Panday, isn’t set to be released until Oct. 2, but one of the musical’s songs is already famous—for all the wrong reasons.

After an outcry on social media over a song lyric perceived to rely on colorism—prejudice or discrimination against people with darker skin tones—the filmmakers announced that they will be changing the song slightly. The lyric in question, which roughly translated to “by merely looking at you, oh fair lady, Beyoncé will feel shy,” will be replaced with “the world will be shy after seeing you” dropping the “fair lady” and Beyoncé mentions.

“We have made the film to entertain audiences and not to offend or hurt anyone,” Maqbool Khan, the director, said. “Since our lyrical arrangement did not go well with few people, we thought why not keeping the essence the same while changing the song a little bit.”

Additionally, the song’s title has been changed from “Beyoncé Sharma Jayegi” to “Duniya Sharma Jaayegi” (meaning “the world will feel shy,” instead of “Beyoncé will feel shy”). Earlier, the song title was simply tweaked to “Beyonse Sharma Jayegi,” changing the spelling of Beyoncé’s name for legal reasons. But though the original lyric used the Hindi word goriya, which translates to “fair or light-skinned lady,” the filmmakers and lyricist have said that it was not meant to be taken literally. “The term ‘goriya’ has been so often and traditionally used in Indian songs to address a girl,” said Khan, “that it didn’t occur to any of us to interpret it in the literal manner.”

Though his stated intention did not match the lyrics’ reception, Khan’s statement does get at a deeper truth: the idea of a “fair lady” being a stand-in for a beautiful woman dates back centuries in South Asian culture, as it does in many others. But just in the last year, colorism in South Asian culture has come under fire in a number of ways. In recent months, instances such as Bollywood stars promoting skin-whitening creams while championing Black Lives Matter and the casual colorist statements in the reality dating show Indian Matchmaking have resulted in a heated discourse surrounding the topic, which, at times, has spurred change. Radhika Parameswaran, a professor in the Media School at Indiana University, Bloomington, spoke to TIME about that context.

TIME: What are some different ways in which colorism manifests itself in Bollywood?

Parameswaran: One of the biggest visual reminders and symbols of colorism is who is cast. In Bollywood, the prevalence of the star system is huge—movie stars make the movie. They become national idols, and people are their fans. Not that you don’t have those types of visual cultures and fans in the U.S., but in India, there is a large population who cannot read or write; films transcend those barriers of literacy, and in a country that’s in the Global South, the role that films can play is huge. The movie stars that have been idealized in Bollywood, particularly in terms of women, have been very, very light-skinned, and that continues today. The settings they’re in are usually very lavish, so light-skinned beauty gets tied to issues of class and upward mobility.

What is the underlying message you get from the lyric “by merely looking at you, oh fair lady, Beyoncé will feel shy”?

It’s the hero addressing the heroine, saying, not only are you white and beautiful, but you would put a transnationally beautiful star to shame, arguing that the Indian light-skinned beauty is even more powerful than a celebrity force coming from America. On a more complicated note, it’s nationalist as well as colorist. It suggests a sort of resistance to American supremacy, but on the other hand, it doesn’t get rid of the problem of local hierarchies of skin color.

If colorism has such a deep history in Bollywood, why do you think this particular moment has caused such an outcry?

There are various reasons. One is that there has been an activist movement against colorism that’s been building momentum over the last ten years I would say, getting more and more amplified. Barkha Dutt, the famous Indian journalist, used to host a show called We the People. She had two episodes, years ago, that talked about colorism and racism, and this discussion made the national stage. Nandita Das, a celebrity example, has been speaking up against colorism. Women of Worth is an on-the-ground charity that has been trying to go into schools and ordinary people’s lives, just engaging the public in this pedagogy of how to get rid of colorism. There are also ordinary people making fun of skin-lightening ads by creating spoofs of them. So there has been a societal contestation of colorism coming from various points of view and various agents.

Then you have Black Lives Matter, which went to India in a way it might not have 20 years ago thanks to social media and the Indian diaspora. All of this combined, it is even surprising that this song was composed, performed and made public. It is quite shocking that these movie-makers didn’t realize this.

In general, what is the role of the diaspora in the colorism debate?

I think the diaspora have been quite active. In India, colorism, even 10 years ago, was easily brushed off as “of course light skin is beautiful.” There was an unquestioned solidity to that claim. It was simply not challenged. And there’s the connection to caste too, so these were all just sort of taken at face value.

The diaspora grew up in a different environment where discrimination is being spoken about, it’s not going away—but it has been spoken about through the language of race. I also think the diaspora, who may have gone to schools and participated in other kinds of experiences in institutions, where perhaps they were a minority and faced racism, are very quick to see this and understand it in a way that perhaps in India, it has taken some time for people to grapple with and understand.

How does colorism move from the screen into the everyday lives of people?

Media messages are not like a hypodermic needle, where you inject it into people’s bodies, and it just becomes part of them. I think it’s a more subtle process and depends on class, education, all of those factors. It’s not to suggest that lower classes and less educated people are more susceptible and practice more colorism, it’s not that simple. I do think in some ways upper classes may be doing it more. But still, it does shape the norms of society. Women in particular keep getting measured against these norms. Can there be cracks in the norms? Sure, but those will be unusual.

The filmmakers decided to change the lyric entirely. Is it rare for backlash to cause such a change?

In some films, there’s nothing to be done. The film is out, it’s released, like Bala, which was a story that featured a dark-skinned heroine, but the actor cast was light-skinned and wore brownface. But I do think this is going to be more of the trend, especially with issues surrounding skin color. This type of colorism, it’s going to get challenged.

Do you think this continued challenging of colorism will result in deeper change?

Here is the thing. It’s one thing to lose the language of “goriya” and the reference to Beyoncé. But does this mean the heroines are going to start being dark-skinned? No. In terms of casting and representation, it’s going to take a long, long time for that to change. Changing a word is fairly easy to do, and cosmetic, and makes the film producers look socially responsible, but changing how the heroines look, that will not be immediate.

This incident comes not long after the skin-whitening cream Fair & Lovely changed its name to Glow & Lovely, though it kept its product the same, again following a social media fallout tied to Bollywood. Do you think companies will begin to make changes even before a controversy comes up?

I think they will tend to wait until an outcry happens first. Bollywood is a mass, popular industry, so they’re going to count on catering to what they think are mass, popular tastes, and I’m sure they’re going to consider whether protests from what they view as a small, elite population that may not even go to their movies are worth it. If a movie is going to be broadcast in the Hindi heartland and all sorts of rural areas and small towns, how much is this type of issue going to be contested in those spaces? We have to ask, who has access to the English language internet, given India’s vast class divisions and rural-urban divisions? Is this a small minority speaking to themselves? In [that] case, Bollywood is going to make cosmetic changes, and I don’t think they’re really going to take this into account in a careful way.

—With reporting by Arpita Aneja

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com