Central Europe in the past week has seen a spike in daily confirmed coronavirus cases, a major setback for a region that largely avoided the first wave of the virus in the spring. The Czech Republic, an E.U. member state of 10.7 million, registered a country record of 1,382 new infections on Sep. 11, bringing the country’s total cases to over 32,400. In the last week, nearby countries Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia have also recorded their highest daily caseloads since the pandemic began.

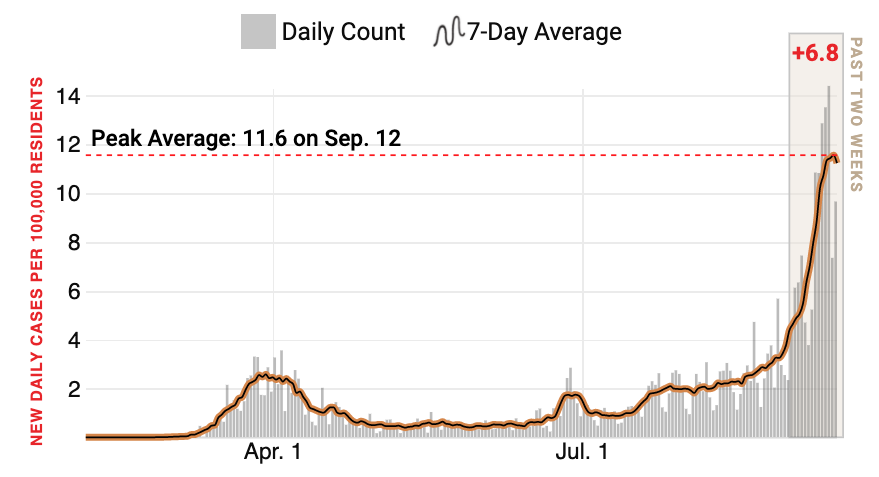

Infections in the Czech Republic previously peaked at around 3 cases per capita (per 100,000 residents) in late March but reached 11.6 cases per capita on Sep. 13. By comparison, the U.S. had 12 cases per capita. Now, the Czech Republic has one of the highest 14-day infection rates in Europe, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Czech Health Minister Adam Vojtech said on Sep. 13 “nobody expected” such a spike in the country.

Governments of central European countries, keen to not impose national lockdowns and prevent further damage to their shrinking economies, have reimposed travel restrictions and renewed social distancing measures for citizens.

The coronavirus pandemic has dealt a major blow to the European economy, particularly countries that rely on tourism. The E.U. economy will decline by an average 8.3% this year, the European Commission said in July. The 27-member bloc, formed after World War II, is expected to fall into the deepest recession in its history. The economies of the Czech Republic and Hungary are predicted to drop by 7.8% and 7% respectively, compared to last year.

Where are cases rising in Central Europe?

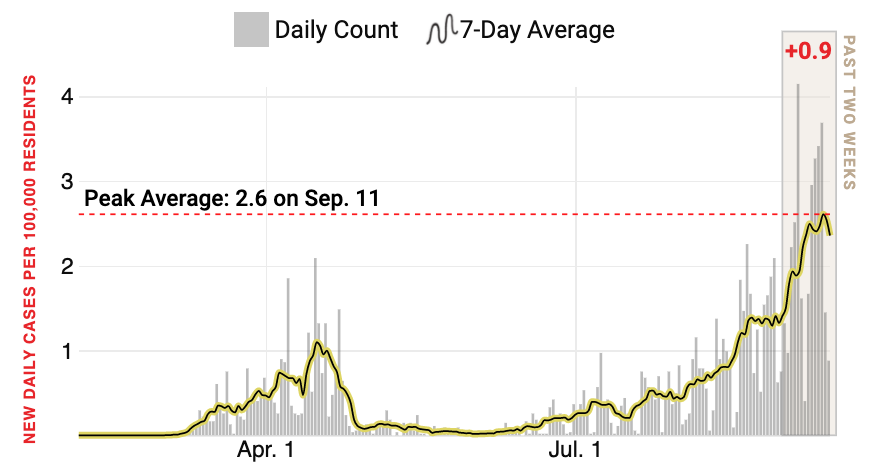

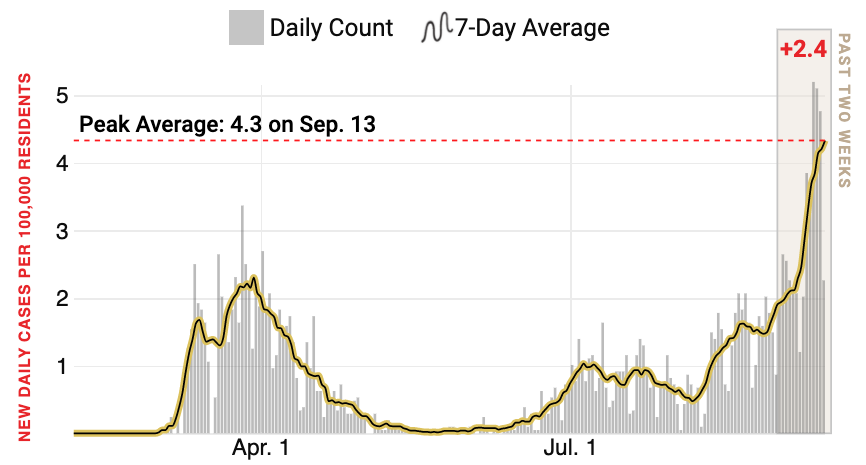

The sharpest rise has been recorded in Czech Republic but other countries nearby, including Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia, are also seeing worrying increases in daily case numbers.

Hungary on Sep. 12 saw its largest daily reported infections since the pandemic began with 916 people testing positive, bringing the country’s total number of infections to 11,825, according to Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Most infections have been registered in the capital city of Budapest.

Slovakia registered a record number of daily cases on Sep. 5 when 226 people tested positive for the virus, according to JHU. Slovenia recorded its highest ever daily caseload with 108 new infections on Sep. 11.

How did Central Europe fare during the beginning of the pandemic?

Central Europe avoided the full brunt of the first wave of coronavirus infections during the spring. On April 15, the U.K. had 159 cases per capita while the Czech Republic had 58 and Hungary, 16.

Luck and foresight initially helped Central Europe to shield itself from the virus, experts say. Some countries in Europe benefited from less international visitors and from going into lockdown when their transmission rates were relatively low. “Central Europe was protected by not being as well connected as international travel hubs and by heeding the warnings from other countries,” says Jennifer Beam Dowd, associate professor of demography and population health at Oxford University.

Why are infections rising in the region?

The spike is likely connected to increased travel combined with a relaxation in restrictions, experts say.

In mid-May, most of Europe began reopening its bars, restaurants and nightclubs, subject to social distancing measures. By mid-June, most of the continent welcomed back travelers from the E.U. and other countries with a stable or decreasing trend of new cases.

The Czech government reopened bars, restaurants and hotels, and allowed gatherings of up to 300 people on May 25 as new daily cases that month were below 111. Hungary reopened all shops and the outdoor sections of cafes and restaurants on May 18 when new daily infections remained under 90. By June 22, the Czech Republic and Hungary had opened their borders to visitors from the E.U. and other countries when new daily infections were below 83 and 29 respectively that month. But in late August the number of daily reported cases in these countries, as well as in Slovakia and Slovenia, began to rise.

Europe as a whole opened up too quickly, says Martin McKee, a professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “There was a great deal of optimism when cases were coming down. But we were only containing it with severe restrictions. As soon as you open up the people, you open up the virus to spread,” he says.

Opening up indoor, poorly ventilated spaces has been particularly dangerous. “Large gatherings, crowds in indoor and even outdoor spaces have undoubtedly contributed to the rise we’re now seeing, says Dowd. “It has a ripple effect that appears later on.”

Experts have linked local outbreaks across Europe to the opening of bars and nightclubs in the Czech Republic, France and Switzerland, among others. At the end of July, at least 98 people tested positive following an outbreak in a nightclub in the Czech capital, Prague.

What are countries doing to prevent the spread of the virus?

The Czech government reintroduced mandatory mask-wearing in taxis, public transport, shops and malls, starting Sep. 10 when daily new cases topped 1,000 for the first time. Officials also ordered bars and restaurants to shut between 12 p.m. and 6 a.m., but stopped short of bringing back other measures that could hurt businesses such as closing restaurants and non-essential stores.

Hungary’s nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who has blamed migrants and foreigners for the spread of the virus, reintroduced an entry ban on all foreigners with some exceptions. The ban went into place on Sep. 1, as the country began to see an uptick in daily cases.

In a Sep. 12 interview with a public broadcaster, M1, Orban said he is drafting a “war plan” to prevent a second wave. “We do not want to introduce a curfew; we do not want movement restrictions,” Orban said. “We want everything to happen as it normally should.” He added that measures to protect the economy and stimulate growth would be introduced in the coming weeks. In the second quarter of the year, Hungary’s GDP fell 13.6% compared to last year (the average decline among E.U. members was 14.4%).

But experts say that prioritizing economic considerations over public health can backfire. “It’s false to frame the introduction of new restrictions as a trade off between health and the economy. If you don’t get the rates down, you can open up the shops but people won’t go into them,” says McKee.

Europe can continue to expect to see a rise in infection transmission in the autumn and winter as people return indoors, experts say, but the level of cases, hospitalizations and deaths are unlikely to reach those seen in the spring peak.

“We’re in a much better place but we need to prepare for a difficult autumn and winter,” says Dowd.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com