At home in Kentucky in mid-August, Mitch McConnell didn’t sound the slightest bit concerned. “The Postal Service is going to be just fine,” the Senate majority leader drawled, echoing the soothing talking points of other Republicans: the Trump Administration was just reforming a 228-year-old institution, and President Donald Trump’s new Postmaster General, Louis DeJoy, was making it more efficient. The same day, Trump described the situation in his own, half-joking way: “I want to make the post office great again, O.K.?”

But the lighthearted talk just highlighted the spreading national panic that had triggered it: less than 80 days before a presidential election that will rely more heavily on voting by mail than any previous race in U.S. history, the great machinery of the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) seemed to be sputtering to a halt. The “operational pivot” DeJoy announced in July, which included restrictions on staff overtime and transportation costs, produced a backlog of undelivered mail, according to postal union representatives. The Department of Veterans Affairs acknowledged that prescription drugs mailed to veterans via USPS had been delayed by an average of almost 25% over the past year. Small businesses, which rely on the affordability of USPS rates, began facing angry customers whose packages were lost in distribution centers for weeks.

At the end of July, the Postal Service itself sounded the alarm, sending warning letters to 46 states, including the electoral battlegrounds of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Florida, alerting them that the USPS might not be able to meet their election deadlines. In all, more than 159 million registered voters live in the 40 states that received the most urgent warnings, according to the Washington Post.

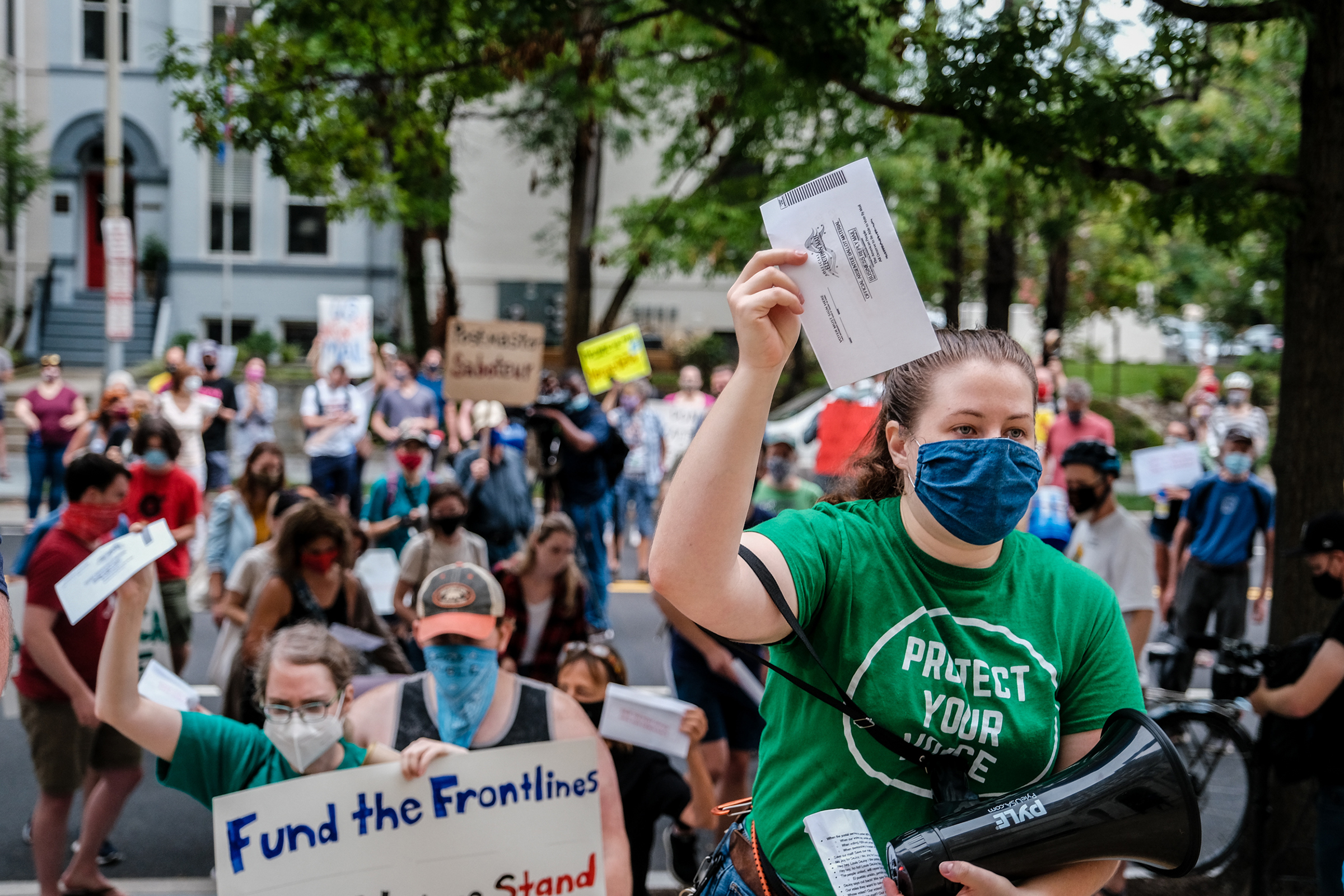

Panicked constituents papered the door of DeJoy’s D.C. apartment building with fake ballots reading, Save the post office, Save our democracy; House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called lawmakers back for an emergency session to vote on a bill to protect the USPS; and Democratic Senator Gary Peters launched an investigation into DeJoy’s operational changes. “It’s a level of concern I haven’t seen in the past,” says Melissa Rakestraw, a mail carrier in Illinois.

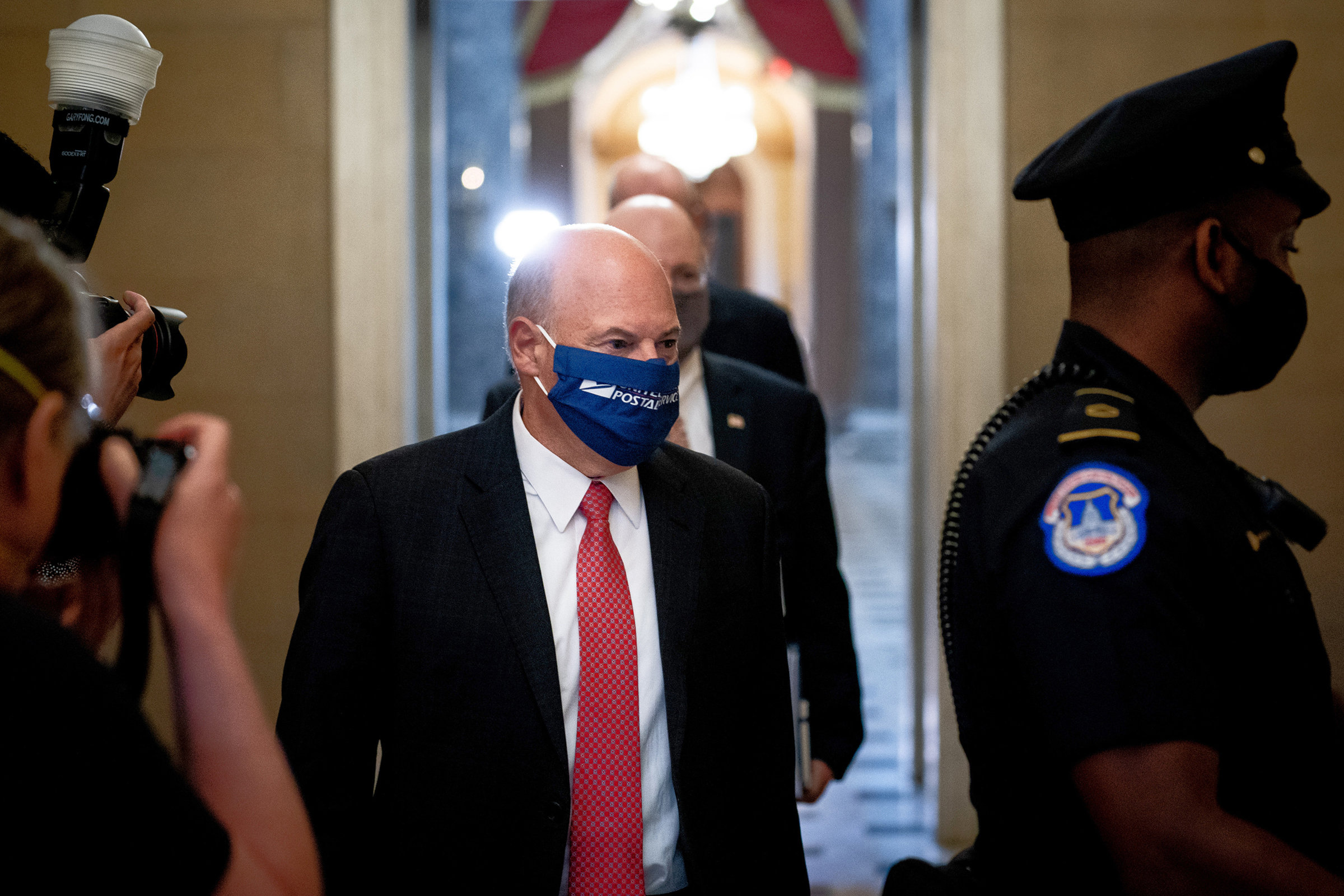

DeJoy, who spent more than three decades running New Breed Logistics, a national supply-chain services provider with 7,000 employees, seemed blindsided by the fallout. The Postal Service has lost money for years, thanks to the rise of the Internet, perennial mismanagement and heavy-handed but ineffective government interventions. The point of his reform agenda, which included reassigning or displacing 23 veteran postal executives, was to cut costs and increase “performance for the election and upcoming peak season,” he wrote in an internal memo obtained by CNN. The slowdowns and backlogs, he said, were “unintended consequences.”

But outsiders spotted a pattern. Behind the daily chaos, Trump’s presidency has one abiding characteristic: using the vast power and reach of the U.S. government to serve Trump’s own political ends. He has repeatedly explained executive actions by pointing to the political benefit they bring him, and a steady parade of his top advisers have offered detailed examples after leaving the Administration in exasperation. Trump tried to turn the Department of Homeland Security “into a tool used for his political benefit,” said the agency’s former chief of staff, by, for example, ordering officials to close stretches of the border in Democraticled California rather than GOP-led Arizona and Texas. The President pleaded with the leader of China to make trade decisions that would bolster Trump’s relationship with crucial farm-state voters ahead of the 2020 election, according to former National Security Adviser John Bolton. And of course, Trump was impeached eight months ago in part for allegedly withholding military aid from Ukraine until the country investigated Trump’s political rivals. The list goes on.

If there were any doubts about the Administration’s motives for the so-called reform of the Postal Service, the President himself seemed to put them to rest. In an Aug. 13 interview with Fox Business, the President said he was blocking Democrats’ proposed $25 billion for the USPS and $3.5 billion for additional election resources because that outlay would help the Postal Service handle a surge in mail voting this year. “They need that money in order to make the post office work, so it can take all of these millions and millions of ballots,” Trump said. “Now, if we don’t make a deal, that means they don’t get the money. That means they can’t have universal mail-in voting, they just can’t have it.”

Less than a week later, DeJoy announced the suspension of much of his reform agenda until after the election to “avoid even the appearance of any impact on election mail.” But the damage may already have been done.

Whatever happens to the USPS in coming months, Trump benefits from having cast doubt on the USPS and mail voting and from having unleashed a specter of impropriety over the core exercise of democracy. When Americans lose faith in the electoral process, voter turnout slumps, and if Trump supporters don’t believe their votes were fairly counted, they’re less likely to accept an outcome in which he does not win.

Most Americans love the Postal Service, and rely on it, regardless of their politics. More than 90% view the agency favorably, according to a 2020 Pew Research Center poll. George Washington himself saw a national postal network as an amplifier of democratic ideals and that egalitarianism continues today: FedEx and UPS pin a premium on letters destined thousands of miles away, while a letter mailed by USPS anywhere within the country costs just 55¢.

But as the Post Office has faced new challenges over the years, lawmakers of both parties have advocated for reform. In 1970, after more than 150,000 postal workers went on strike, halting the delivery of vital mail, the Democraticled Congress oversaw a reorganization of the USPS, demoting the Postmaster General from the Cabinet and, crucially, cutting off taxpayer support: the Postal Service as we know it today funds itself from its own sales.

With the rise of the Internet, those sales have plummeted. In 2001, the USPS moved more than 103.7 billion pieces of first-class mail; in 2019, the number was almost half that, at 55 billion. Rising fuel prices and trucking costs and an uptick in the number of packages have exacerbated the problem.

In 2006, Congress again went after the Postal Service, this time passing a bipartisan bill–it was approved by unanimous consent in the Senate–mandating that the USPS pre-fund health benefits for its retirees and invest those funds in government bonds, which offer dismal returns. It is a requirement that no other entity, public or private, must meet, and it costs the USPS more than $5 billion per year–roughly 7% of its total operating costs. The requirement is responsible for a large portion of the agency’s annual shortfall, according to its financial reports. Last year, USPS tallied $79.9 billion in expenditures and finished the year with $11 billion in outstanding debt.

The parties have long been divided over how to fix these deficits. For decades, Democrats accused Republicans of sabotaging the Postal Service in an effort to privatize it. Republicans denied the charge and defended their reform efforts by pointing, not incorrectly, at the USPS’s hemorrhaging balance sheets. But then came the Trump Administration, with its tendency to say the quiet part out loud. In 2018, the White House suggested for the USPS a “future conversion from a government agency into a privately held corporation.”

Over the past five months, this relatively obscure policy fight was transformed into a democracy-defining battle. In April, the USPS asked Congress for $75 billion to help it weather the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. When stores shuttered, the Postal Service saw first-class mail, its most profitable product, decline, while the volume of packages–the most labor-intensive to deliver–surged, as Americans increasingly shopped online. Democrats are pushing for more USPS funding in their latest relief bill, but the White House has so far resisted. (In late July, the Treasury Department authorized the agency to borrow up to $10 billion under strict conditions.)

In May, DeJoy’s appointment to the top Postal job seemed to confirm Democrats’ worst fears–that what had been an ideological push to privatize the Postal Service had morphed into an effort to swing the election for Trump. DeJoy “has deliberately enacted policies to sabotage the Postal Service to serve only one person, President Trump,” said Representative Gerald Connolly of Virginia, whose House subcommittee oversees the USPS.

Democratic lawmakers had no say in the appointment of DeJoy, who donated more than $1.1 million to the Trump Victory campaign fund from August 2016 to February 2020. Under normal circumstances, the USPS’s Board of Governors, which appoints the Postmaster General, is bipartisan: Presidents name each of the nine Senate-confirmed members to seven-year terms. But Senate Republicans blocked Obama’s nominees, allowing Trump to inherit an empty board, which he happily filled with like minds.

Unable to prevent DeJoy’s rise, congressional Democrats helplessly pointed at his apparent conflicts of interest. At the time he was appointed Postmaster General, the GOP megadonor held at least $30 million worth of stock in a supply chain company that contracts with the USPS, raising questions of whether he is violating ethics rules that prevent officials from participating in government matters affecting their personal finances. DeJoy also holds stock options that allow him to purchase Amazon shares at a below-market rate. As Amazon increases the proportion of packages it delivers itself–and toys with the idea of delivering non-Amazon parcels, too–the retail giant is quickly becoming a direct USPS competitor.

DeJoy’s announcement on Aug. 18 that he would suspend much of his reform agenda until after the election may seem like a win for Democrats. In the coming weeks, DeJoy will be hauled in front of both the House and Senate for hearings, and a congressional investigation into this summer’s events is ongoing. But the politics aren’t so simple.

DeJoy’s reversal left a host of unanswered questions. What would happen to the dozens of mail-sorting machines and drop boxes that have already been hauled off? When will workers’ overtime be approved? Will postal workers be able to take more than one trip per day? Will states have to buy more expensive postage to circumvent delays? Without proactive moves to safeguard mail delivery, hundreds of thousands of ballots may still end up in the trash. In 32 states, ballots must arrive by Election Day, according to an analysis by the National Conference of State Legislatures. During this year’s primaries, at least 65,000 mailed ballots were discarded for various reasons, according to NPR. While that represents only about 1% of the ballots in most states, according to the NPR analysis, tiny margins matter: in 2016, Trump won Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, each by margins of less than 1%, but that was enough to claim 46 electoral votes–and the presidency.

The best-case scenario for the agency is that Congress gives it emergency funding, public scrutiny persists and DeJoy makes good on his promise to “deliver the nation’s election mail on time.” But that can’t undo what’s been done.

By discrediting the Postal Service and mail voting, Trump has already tainted the election results, whatever they may be. According to an Axios-Ipsos poll in August, 47% of voters supporting Vice President Joe Biden said they planned to vote by mail, compared with just 11% of Trump supporters. If that disparity holds true in November, the fallout could be bad for both parties. Older and rural voters, who have in the past relied on mail ballots and tend to support Republicans, may be discouraged from voting at all. Trump could also appear to be ahead on election night among in-person voters, only to be overtaken as disproportionately Democratic mailed ballots are slowly counted–days and weeks later.

It’s not hard to imagine the damage that a hung election, like the 2000 Bush-Gore debacle, could exact in the era of Trump-fueled disinformation. Democracy, after all, is not unlike flying in Peter Pan’s world; if you stop believing in it, it ceases to work.

–With reporting by ALANA ABRAMSON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com and Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com