Freemasonry is the world’s most famous secret society. Its secrecy, indeed, made it into one of history’s most contagious ideas—and thus its history offers a striking lesson in the power of mystery.

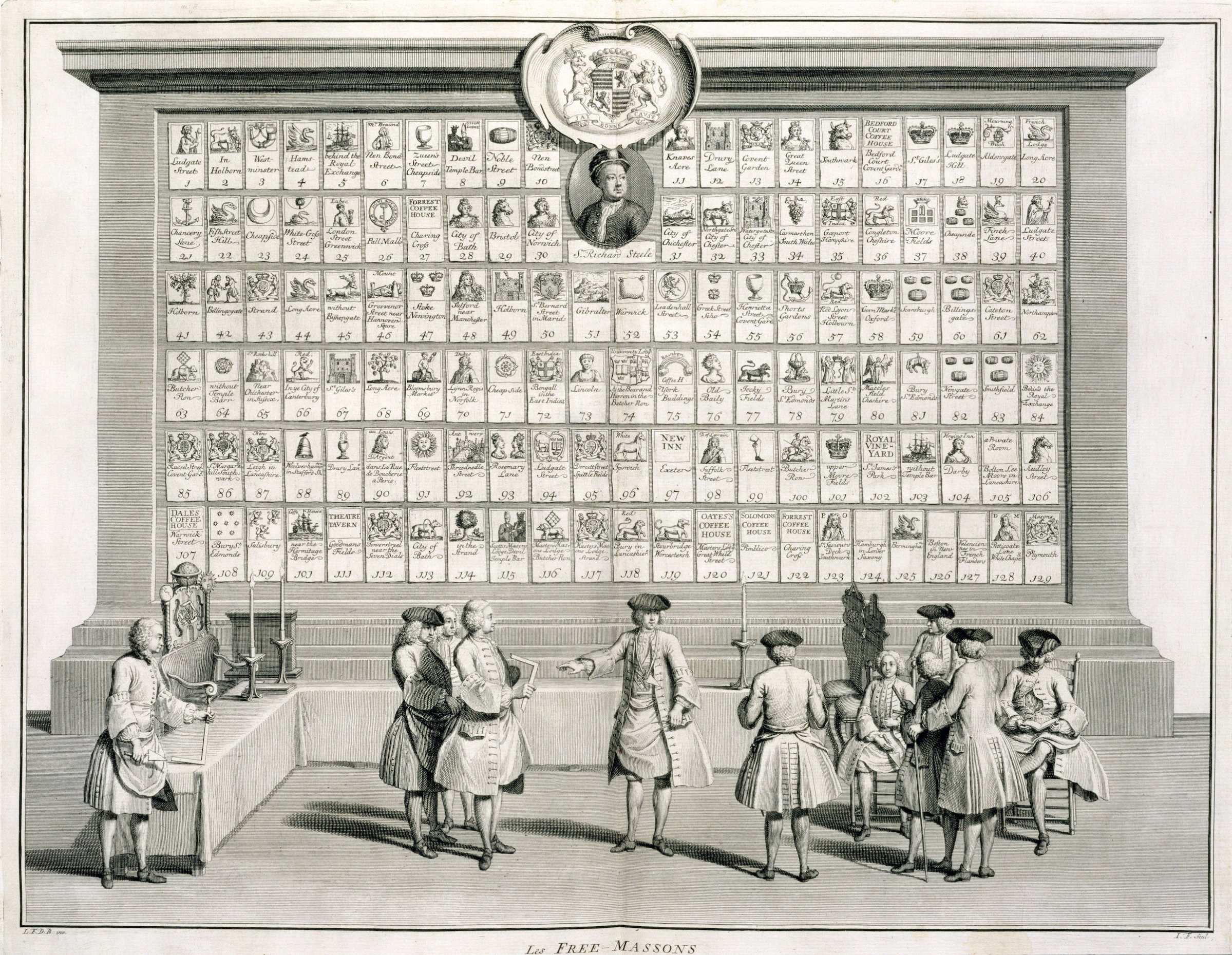

The Freemasons trace their foundation to London in 1717. The Craft, as members call it, was based on a fraternal bond created by ritual and symbol. Its rules prescribed a formal equality between all members, whatever their race, creed or class. The aim was moral education: building better men, just as the stonemasons of old had built cathedrals and castles. Crucially, however, all of this was to be conducted in seclusion from the outside world, and it involved learning secrets and swearing to keep them.

Whatever secrets the Masons were guarding, they made for a bewitching recruitment tool. Who could resist the promise to join an élite in possession of occult truths? Within a couple of decades, the mystique of Freemasonry made it a worldwide phenomenon: there were Lodges everywhere from Amsterdam to Aleppo, from Charleston to Calcutta. The Craft spread on the currents of an earlier era of globalization: empire and commerce, warfare and intellectual exchange.

Its founders quickly discovered that they could not control their creation. Within the group, Masons disagreed passionately about arcane rites and procedures, splitting into rival branches based on their beliefs. They also fissured on issues of race and gender. Were women worthy to be admitted to the great mysteries? Were Jewish or Black people? Externally, the Masonic brand was borrowed and bastardized. If you had a secret, then organizing yourself like the Freemasons seemed a good way to keep it. Groups as varied as the Ku Klux Klan (to conceal the identity of white supremacist terrorists), the Sicilian mafia (crime), and the Mormon Church (bigamy) all incorporated the furtive strands of the Masonic DNA.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, suspicion has followed the Brothers’ every step. The Pope excommunicated them very early on, seeing them as covert heretics; any Catholic who joins the Masons is still putting his soul in peril, according to the Vatican. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, a refugee priest in London by the name of the Abbé Barruel wrote Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, a five-volume analysis of the Revolution’s causes that blamed everything on an evil scheme hatched within the Lodges. Barruel, in short, was the world’s first conspiracy theorist. Since then, the Freemasons have been blamed for the “murder” of Mozart, the outbreak of the Russian Revolution and a cover-up at the inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic—among a host of other nefarious deeds.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Conspiracy thinking drove Mussolini, Hitler and Franco to crush the Craft. Today, Freemasonry is banned in China, and everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco. The Charter of Hamas describes Freemasonry as a “network of spies” created by the Jews to “destroy societies and promote the Zionist cause.”

Freemasonry’s secrecy, which gives these feverish imaginings free play, is like the water at the bottom of a well. The men who built the well know how deep it is. The rest of us can only peer down and wonder what might lurk below, while the dark surface mirrors back our fears.

Ask the Freemasons today about secrecy, and you will receive a pat response. “We are not a secret society,” they will say, ”we are a society with secrets.” A committee deep in the bowels of some Grand Lodge or other evidently thought that this formula would put the issue to rest. But, of course, even moderately skeptical non-Masons will still wonder. What secrets? What are they hiding? A whole exposé genre claims to provide the answers that the Masons seem reluctant to hand over.

Yet the Masons’ notorious secrets have never actually been all that secret. The first exposé dates back to 1730. Today a couple of minutes on Google is all it takes to find out everything you might want to know.

Strip away all the protocol, and we find that Masonic secrecy is multifaceted: it is both more and less than what the Google results will tell.

During his initiation rites, a Mason learns many secrets: such as the strange handshake that vouches for his Masonic status. (Masons call it the “grip.”) The symbols whose real meanings Masons learn are also secret. Just to make sure, new Masons also have to swear secret, blood-freezing oaths not to betray the secrets they have learned: “Under no less a penalty… than that of having my throat cut across, my tongue torn out by the root, and my body buried in the sand of the sea at low water mark.”

So Masonic rituals consist of secrets, wrapped in secrets, wrapped in secrets. Once the wrapping is removed, what is revealed are moral principles of utterly disarming banality. Be a nice fellow. Learn more about the world. Remember that death puts things in perspective. The great secrets of Freemasonry are all motherhood and apple pie.

Is that really all there is to it? Even many early Craftsmen were underwhelmed, and formed new versions of the brotherhood to protect proper secrets: like a cure for old age, or the formula for turning base metal into gold. Others sought to fill the secrecy void with utopian politics: both the Illuminati of Bavaria and the Charcoal Burners of Italy were variants of Masonry that offered initiation into a revolutionary plan.

They were all missing the point. Masonic secrecy is not a way of hiding anything at all. It is the wrapping, and not what it contains, that is key. Secrecy is a way of enveloping bonds of fellowship in solemnity and sacredness. Born during the Enlightenment, when the grip of religious orthodoxy on private and public life was beginning to be relaxed, Freemasonry offered a passage to a more secular world. It was a half-way house: its secrecy made it like a religion, without containing any dangerous theological ideas.

The first Freemasons could hardly have predicted the global shaggy dog story of success and notoriety that they would generate. The lesson of their fascinating history is simple: make yourself misunderstood.

John Dickie is the author of The Craft: How the Freemasons Made the Modern World, available Aug. 18 from PublicAffairs.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com