If there were any intelligent beings on Mars, they’d likely be confused by a little plaque recently added to the side of the SUV-sized Perseverance Mars rover, which lifted off at 7:50 AM local time on Thursday morning from Cape Canaveral in Florida and is set to reach Mars in February. Nobody had planned any late additions to the rover—but no one had planned on a lot of things this year, least of all the COVID-19 pandemic which continues to burn across the world.

As it did with pretty much everyone else in the United States, the pandemic forced the Perseverance team to work from home if they could, social distancing in the factories and clean rooms if they couldn’t. As a nod to the challenges that presented, the flank of the rover now carries the medical community’s snake-and-staff caduceus symbol, along with a picture of Earth and the flight path of a spacecraft soaring away from it:

Perseverance is not the only ship that recently embarked on the seven-month journey from the troubled blue planet to its mysterious red neighbor. On July 19, the United Arab Emirates made its first bid to join the Mars game, launching the 1,360kg (3,000lb.), 3m (10ft.) tall Amal, or “Hope,” spacecraft on a mission to orbit Mars for at least two years while studying its atmosphere. Just four days later, China launched its Tianwen-1, or “Questions to Heaven,” spacecraft, a three-part ship with an orbiter, a lander and a six-wheeled, 200kg (440lb.) rover.

The ships on the Mars-bound international convoy will by no means be alone when they arrive. Mars, a cold, dry desert planet, is rapidly becoming something of a worker-bee world. Six spacecraft—three American, two European and one Indian—are currently in Martian orbit, while one stationary lander and one rover, both American, are busy on the surface. (A joint Russian-European mission, ExoMars, was also planned for this summer, but has been postponed to 2022 due to engineering problems.) What began as a collection of individual ships built by individual nations is rapidly becoming nothing short of an international scientific infrastructure hard at work on another world.

“There is lots of international collaboration both currently [going on] and planned for the future,” says Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “Of those six spacecraft that are currently in orbit at Mars, we have collaborations on all of them. We are absolutely huge supporters of the transparent and open sharing of science discoveries.”

There are an awful lot of those discoveries to be made. The UAE’s Amal will investigate how Mars’s atmosphere—once thick and potentially able to sustain life, but now just 1% of the density of Earth’s—was stripped away by the solar wind, a slow loss of air that continues today. The Chinese rover will, like NASA’s still-active Curiosity rover, investigate the chemistry—and the hoped-for biochemistry—of the Martian soil.

But Perseverance, the fifth in a line of Mars rovers built by the experienced hands at NASA since 1997, is easily the most remarkable of the new explorers. There are its 23 cameras, for one thing. There’s its 2.1m (7ft)-long robotic arm, equipped with a rotating wrist, a rock drill, a camera of its own and a system to analyze the molecular structure of the Martian soil. There’s its on-board brain that allows it to map its surroundings and autonomously travel up to 200m (656 ft.). Oh, and it has its own helicopter. Really.

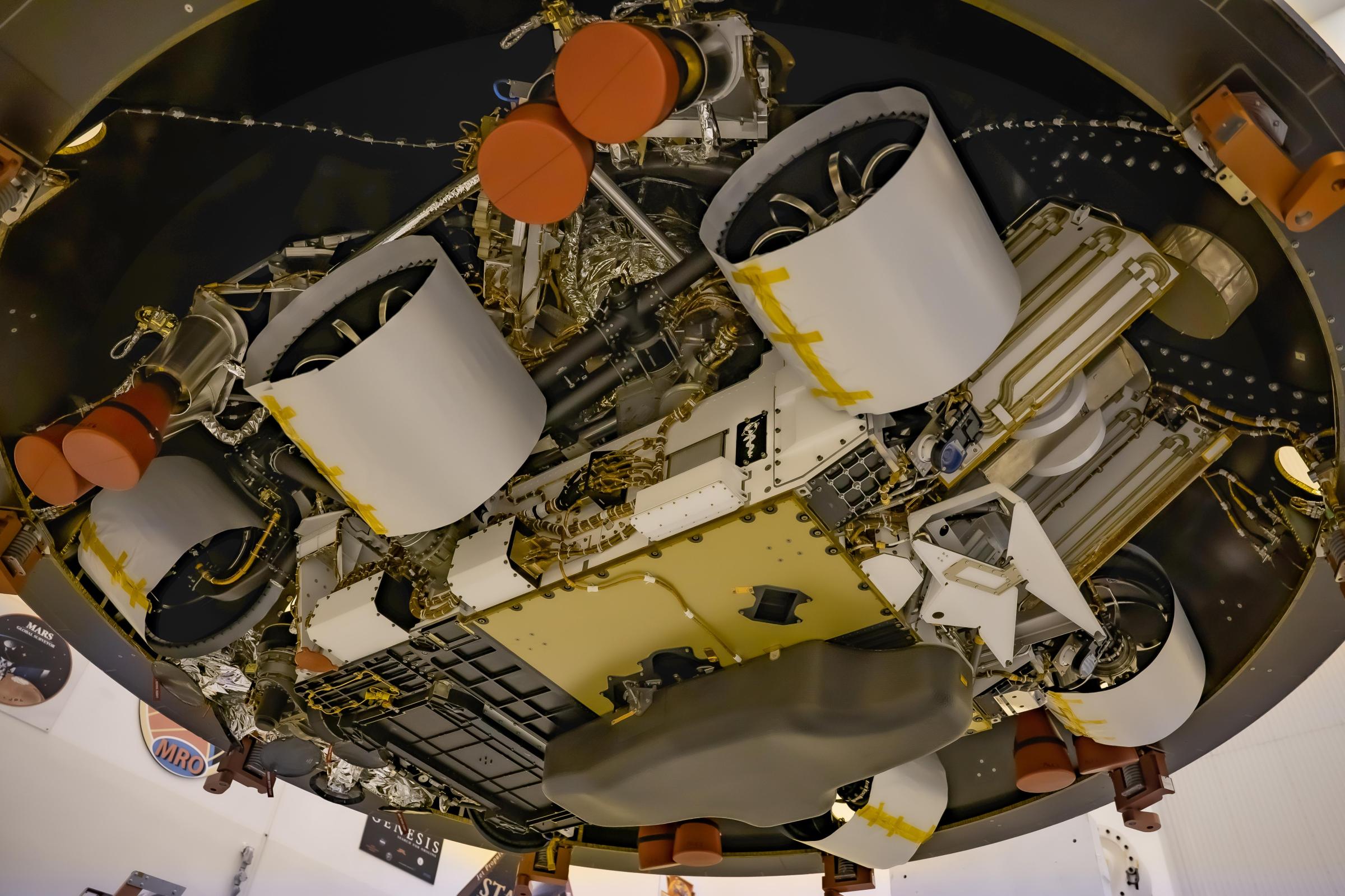

Attached to the underside of Perseverance is a .45m (1.6ft.), 1.8kg (4lb.) extraterrestrial flying machine, with a pair of 1.2m (4ft.)-long blades. The little chopper, dubbed Ingenuity, is just light enough to gain purchase in the thin Martian air. It will spend a month or so taking short test flights of up to 90 seconds long and 4.5m (15ft.) in altitude, never venturing far from the rover. Ingenuity carries no instruments except for a camera—a must-have for capturing the first ever helicopter flight over Mars—and is very much what NASA calls a technology demonstration.

“That means that it’s not required for the mission to be successful,” says Glaze. “But of course we want it to fly. Of course we want it to be successful.”

A much more important part of Perseverance’s mission will be its search for biology. For all of the talk about looking for life on Mars, previous and ongoing missions have not and are not equipped to do that. Rather, they have only looked for the chemical and environmental conditions that could allow life to thrive—and in some respects, they’ve found plenty. Mars is a world etched with dry river beds, stamped with ancient sea basins, marked by deep depressions that could only indicate long-vanished oceans. Perseverance is landing in one such place: the Jezero Crater, north of the Martian equator, which is lined with both inflow and outflow channels indicating it was once a vibrant sea. Previous rover analyses in similar locations have discovered chemicals and compounds that form only in the presence of water, proving that Mars was once, like Earth, exceedingly wet.

Perseverance will go further. While analyzing soil chemistry like its predecessor rovers, It will also take the critical step of preparing Martian samples to be returned to Earth. There are 43 test tube-sized sample containers on board the rover, and they go far beyond the simple rock boxes the Apollo crews used when they explored the moon. “They are ultra-clean,” says Ken Farley, project scientist for the Perseverance mission. “And by ultra-clean I mean they are surely the cleanest things that have ever flown.”

That’s critical, because Earth is crawling with microbes, which could easily contaminate the tubes even in a sterilized clean-room. That would be a very bad thing if you’re looking for Martian life, since it would be impossible to know if an organism you find in the soil was actually Martian, or originated on Earth and then hitched a ride to Mars and back. To avoid that, the tubes were made of titanium and then treated with nitrogen to convert the material to titanium nitride. “Titanium nitride is a wonderful substance that passivates the surface, which means that organic molecules won’t stick to it,” Farley says.

But once Perseverance collects its samples, the question becomes: how do you get them back to Earth? The answer: you don’t—at least, not yet. For now, Perseverance will leave the tubes it fills with Martian samples neatly on the ground, then go about the rest of its mission. The samples are set to be picked up on NASA’s next—and even more ambitious—Mars trip.

Set for launch in 2026, the sample-return mission will begin with the launch of the so-called “fetch rover,” which will land at the same site as Perseverance and gather up the tubes. A small onboard rocket called the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) will then loft the sample tubes into low Martian orbit. The samples will then be flown back to Earth through a collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), which will launch its own probe, also in 2026, to fly to Mars, rendezvous with the MAV, gather the test tubes and bring them back home, where they will land in the southwest U.S.

It’s a decidedly complicated mission, involving three launches from Earth (including the one just this morning) and one from Mars, and nobody pretends all of the technicalities have been figured out yet.

“What you do in science and especially in exploration is you have a plan and you beat it with a stick,” says NASA associate administrator Thomas Zurbuchen. “You want to make sure you understand every single problem with it. So frankly, we’re beating it with a stick right now.”

The fact that NASA and the ESA are doing that work together says something encouraging about both exploration and humanity as a whole. We may be an exceedingly fractious species on Earth, but as we reach out to Mars—as Americans and Europeans and Russians and Indians and Emiratis and Chinese and surely more in the future—we are reaching out as a species as well. If we can cooperate on a desert world like Mars, think what we could accomplish by doing the same on the garden world that is Earth.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com