Border Patrol finds a migrant man frozen to death on a snow-covered mountain in the desert. A Spanish-speaking officer phones the dead man’s father, who inquires, through tears, about how he can recover his son’s body. “Are you in the United States legally?” the officer wants to know.

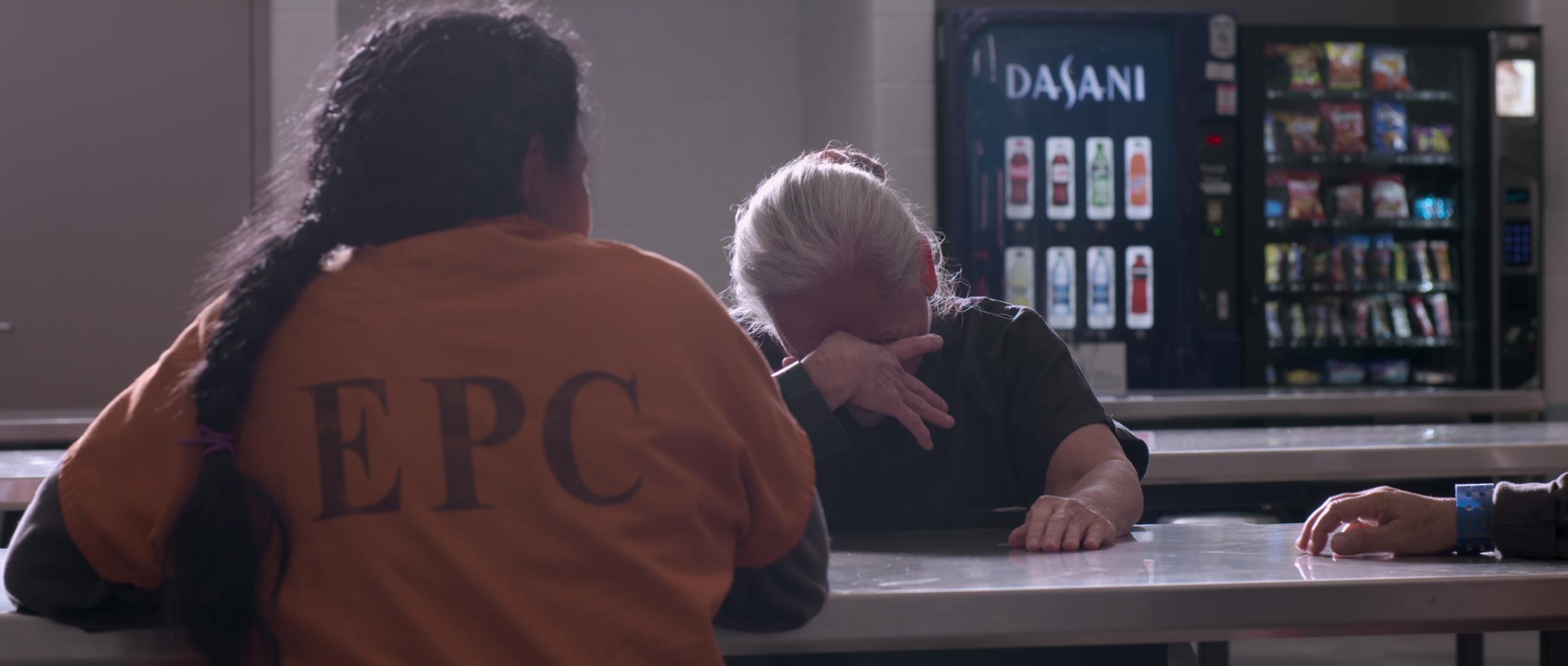

A tiny, white-haired woman explains that she and her granddaughter sought asylum in the U.S. after MS-13 attempted to force the 12-year-old into marriage. When we meet the grandmother, she’s been in Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody for 17 months.

A young father in handcuffs and chains breaks down crying as he recalls how his 3-year-old son grasped onto his leg when ICE separated them. “Where,” he demands, “are the good Americans?”

These are just a few of the vignettes that have been haunting me since I watched Immigration Nation, an explosive documentary that comes to Netflix on Aug. 3. Trophy co-directors Christina Clusiau and Shaul Schwarz’s six-part series offers a complex, 360-degree view of the American immigration system, combining in-depth research, empathetic storytelling and bold investigative journalism into a uniquely urgent humanitarian appeal. The project has already made national headlines thanks to pushback from ICE and the President. The New York Times recently reported that the Trump administration tried to block the filmmakers’ use of some footage, threatened legal action against their production company and “fought mightily to keep [the series] from being released until after the 2020 election.” Clusiau and Schwarz’s attorney told the paper that ICE’s intimidation tactics were even more aggressive. The government was probably right to be worried. As damning for the executive branch as it is illuminating for civilians, Immigration Nation is easily the most important TV show of the year.

Beginning in 2017, the filmmakers spent three years following people on all sides of the immigration crisis, from families separated at the border, migrant workers and refugees to lawyers and activists. They were given surprising access to ICE—interviewing officers, filming inside detention centers and even riding along on raids. At first, this intimacy can be disconcerting. The series opens with the staff of ICE’s New York City Field Office carrying out operations and complaining that they’ve been called racists as protesters amass outside their headquarters. Viewers who objected to the pro-police sympathies of newly canceled shows such as Cops and Live PD, as I did, might worry that the filmmakers will dehumanize undocumented immigrants. But this introduction is something of a fake-out. By showing us how they documented ICE officers without apparent judgment, Clusiau and Schwarz demonstrate how they were able to witness the agency at its most alarming.

With cameras rolling, some officers praise the Trump administration’s harsh policies (“We’re finally able to do our job,” one woman enthuses). Others snicker at undocumented people’s efforts to defend themselves and their families. We hear an ICE spokesman spout the statistic that 91% of those arrested by the agency are criminals, only to have an on-the-ground colleague clarify that in his locality “we’re about a third crim.” Some scenes that the government reportedly hoped to suppress feature ICE officers breaking laws, misleading immigrants about their rights and arresting two “collaterals” (undocumented people who were not supposed to be targets) during an operation aimed specifically at apprehending a third person.

It’s no mystery why ICE and the Trump administration panicked over this video evidence of deception and cruelty. Yet ultimately more disturbing, because it’s harder to dismiss as the actions of a few bad apples who may be investigated or fired, is the extent of the systemic dysfunction and delusion Immigration Nation reveals. A common refrain among ICE officers, who insist to immigrants in their charge they’re only executing decisions made by legislators and courts, is “It’s not up to me.” (Never mind that immigration judges don’t have the same independence enjoyed by their counterparts in the judicial branch, either.) Clusiau and Schwarz don’t editorialize—a wise choice because their observations speak for themselves—but it’s wasn’t hard for me to detect echoes of Nazis who claimed to be “just following orders” or participants in the 1960s Milgram experiments on obedience to authority, who believed they were administering painful electric shocks to peers under the direction of scientists.

These workers appear mired in, and sometimes overwhelmed by, cognitive dissonance. In the harrowing final episode, which explores how a Clinton-era policy known as “prevention through deterrence” has led to thousands of migrant deaths and fed a human-smuggling industry dominated by organized crime, a member of the Border Patrol’s Search, Trauma and Rescue Unit (BORSTAR) tenderly cares for a Guatemalan man suffering from dehydration. Soon after, he remarks to a colleague about how fun it is to aid in apprehensions. Government employees of all races who seem to be basically decent, thoughtful people admit that they feel sorry for those whom they arrest and deport, in some cases acknowledging that their targets have no better option than to try entering the U.S. illegally. In El Paso, an officer charged with walking deportees over the border cheerfully suggests that when they come back, they “try to do it the right way.” But as the filmmakers point out, “the right way” barely exists anymore. As a result of the President’s controversial “Remain in Mexico” policy, tens of thousands of asylum seekers who previously would’ve been admitted into the country to plead their cases must now wait for months in de facto refugee camps.

Yet despite how much insight it provides into the organizational psychology of the U.S. immigration system, Immigration Nation is most powerful—and seems most likely to change minds in our politically polarized present—when it profiles the immigrants themselves, all of them more memorable than anyone from ICE. The filmmakers put a human face on the often-overlooked struggles of deported veterans by following César, a Marine who had lived in the U.S. since he was toddler before being sent “back” to Mexico, as he attempts to secure his status so that he and his wife can start a family. We meet Bernardo in detention; he traveled to the States with his son but remained in ICE custody after the boy was released to live with his sister-in-law, who is also undocumented and is afraid of taking on the additional risk. The show zooms out from there, traveling to Guatemala to visit the impoverished wife and younger children Bernardo left in a last-ditch effort to find work.

It’s these human portraits that allow Clusiau and Schwarz to highlight so many aspects of this decades-old, newly intensified humanitarian crisis in the space of just six hours. (A few glaring omissions, such as the Trump administration travel ban that opponents dubbed a “Muslim ban” because of the restrictions it placed on refugees, immigrants and visitors from several nations with large Muslim populations, suggest room for a sequel.) A docuseries that could have fallen into the Cops trap of trading rare access for a sympathetic portrayal of state power, as ICE must originally have hoped, thus turns out to be a sort of anti-Cops. Rather than a battle between good vs. evil, or white hats vs. “bad hombres,” Immigration Nation makes a compelling case that what’s happening at our southern border is a test of American empathy. And as it stands, we’re failing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com