Over the last several years, anti-LGBTQ “purges” have taken place in Chechnya, a conservative Russian republic. Chechen officials, according to many reports and testimonies, have rounded up people they believe to be gay, tortured them and then released them to family members who were encouraged to commit “honor killings.”

Fearing for their lives, some young queer people have fled the predominantly Muslim region with the hopes of finding safety outside Russia. Welcome to Chechnya, a documentary by David France premiering June 30 on HBO, follows these refugees and the activists going to extraordinary lengths to help them escape.

Chechen officials have denied that purges took place, saying in one case that gay people do not exist in that part of Russia and if they did, their relatives would be so ashamed that they “would have sent them to where they could never return.” European countries have criticized Russian authorities for allowing a “climate of impunity” in the republic.

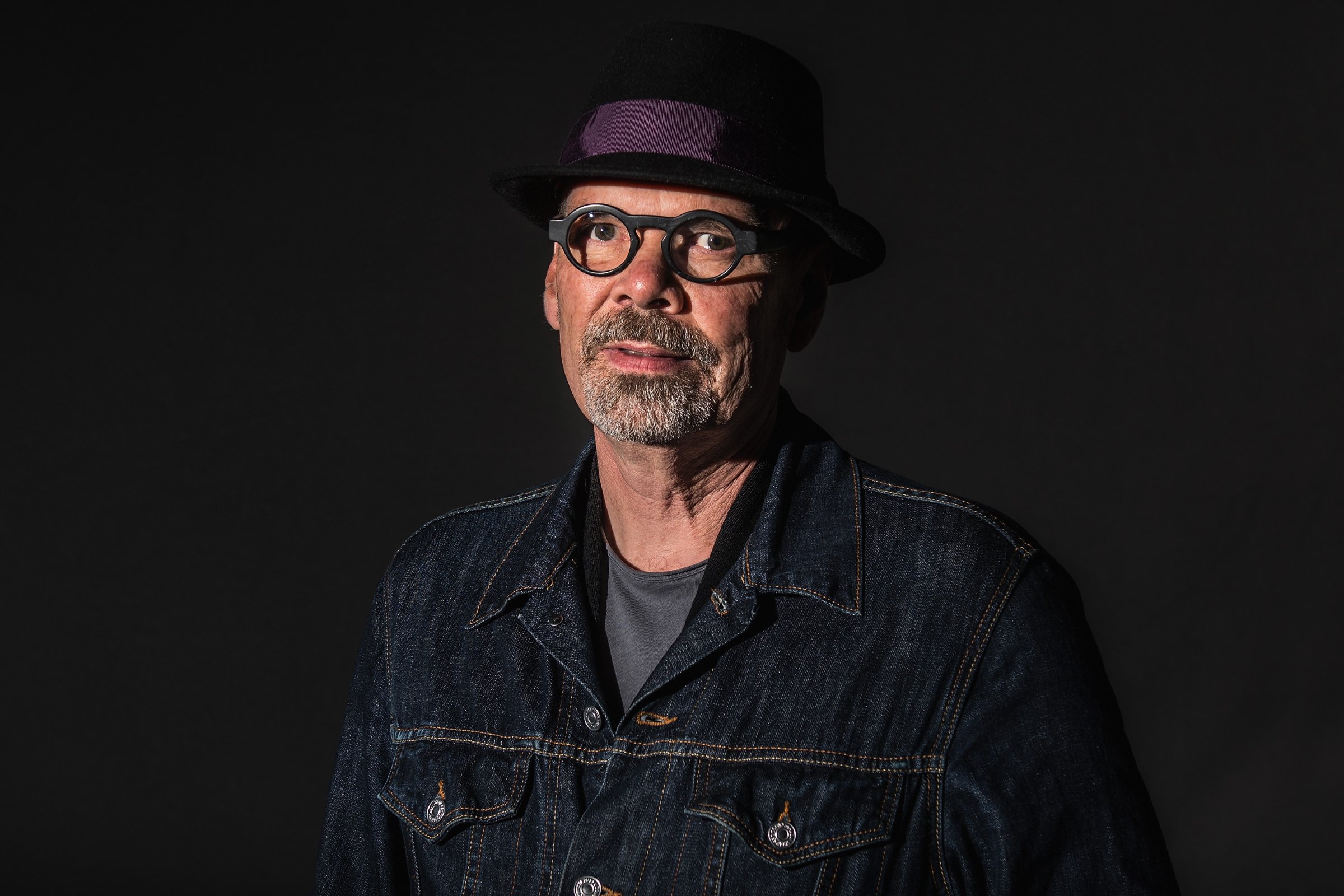

Welcome to Chechnya is France’s third documentary. His first, 2012’s How to Survive a Plague, based on his own book of the same name, reflected on the early years of the AIDS epidemic in the U.S. and earned numerous awards including an Oscar nomination. His second, 2017’s The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson, explores the life of the prominent activist. Ahead of the release of his new film, TIME spoke with France about the extreme security measures he put in place for Welcome to Chechnya, what he thinks of the government’s denials and why, despite the risk, Chechens were willing to tell their stories.

TIME: When did you realize you wanted to make this film?

David France: I decided to do the film the minute I realized that this activism was taking place, desperately, in a world that wasn’t helping. No one was covering it. So I just left for Russia.

After working on the film for 18 months, how would you describe the dangers of being gay in Chechnya?

It’s not possible to live if it’s known that you’re gay. The campaign in Chechnya is a cleansing of the blood, as it has been described. It is a mission to round up and exterminate LGBTQ Chechens, and that doesn’t end when people run away. It only ends when they’re dead.

How did you proceed once you got to Russia, given that your subjects would be in danger if they or the film were discovered?

I had an encrypted phone call with the staff from the Moscow Community Center for LGBT+ Initiatives [an organization helping individuals get resettled in other countries] and presented it to them. They felt it was important to show the world what was happening but said that not everyone would want to be in the film, so we made certain ground rules. I hired a local cameraperson and we moved into [one of the safe houses the center was operating].

What were among those ground rules?

We were careful not to take taxi cabs, for example, directly to the place. We were careful to alter our routes and to not appear in any way to be a film crew. We used a very small consumer camera, beat it up and made it look like a tourist thing. When we were filming in public, we taped up the plastic body so that no lights would be shown and operated it with a cell phone. But there were places where we couldn’t even use that.

Many people in the film are “digitally disguised,” with the faces of other people imposed on their own to hide their identities. Was that something you promised at the outset?

That was one of the security issues that I had with the people who were escaping, to get them to trust me. I signed little deals with everybody that said I wanted to shoot their faces, which they hadn’t let anybody else do, and I would protect my footage with my life. I would somehow find a way to disguise them and I would bring that back to them for their approval.

And had you used this technology before? What is it?

We call it face doubling. This technology has not been used before. We had additional burdens: that we could not move any of our footage over the Internet and we couldn’t work with the footage in an open studio setting. So we had to set up a kind of windowless room in order to keep with our security protocols and hire our own team to do it. We developed the IP with [software architect] Ryan Laney. For documentary filmmakers, this is a brand new tool.

Even with the digital disguises, why did people agree to do this? What did they tell you about why it was worth it to them to risk being on film?

Because they want this to end. And so they would participate if it had a chance of getting us closer to safety in Chechnya. They want to go home. They want to go back to their moms. They’re so young, most of them, to be flung out into the world like this. They want to at least be able to call home, and they can’t even do that. This way they were allowed to tell their stories and affirm their lives in a way that didn’t put them in deeper peril.

Do you see the film as a rebuttal to Chechen and Russian officials who say no persecution has taken place or no investigation is necessary?

Yes, it’s absolutely a rebuttal.

What do you feel is the most compelling new evidence you’re offering, knowing we still don’t see the torture itself?

We are telling stories. We are letting people narrate their journeys. And through the activists who are rescuing them, we’re seeing what the danger is to anybody who is queer in Russia and trying to expose this issue in their own country.

Do you believe Russian President Vladimir Putin is responsible for putting a stop to this? In your highest hopes, what changes after this film?

Putin is setting the tone here. Putin is rolling back LGBT rights in Russia. Putin is fomenting hatred for queer people in Russia. Putin has given permission for all his regional leaders to carry that out in their own way, and that’s why this is happening now. Putin could call up [Chechen leader Ramzan] Kadyrov and say, “Stop,” and Kadyrov would stop. And if we can get that, that’s a beginning.

What else needs to happen?

Kadyrov needs to go, and so do his henchmen. They run a regime of thugs, not just thuggery against the LGBTQ community. They were [threatening] people with pipes for not observing lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic there. It’s a brutal, brutal regime.

Besides investigations and pressure campaigns already going on, what should the international community be doing?

I think it’s really going to have to come from higher levels. European leaders, anybody doing political business or economic business with Russia should demand equal treatment. And they’re not. Washington could stop this.

Given Trump’s record on LGBT rights and his relationship with Russia, do you have hopes of Washington actually stepping in?

No, not while he’s in office.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com