Days before she tested positive for COVID-19 in early April, Tanya Beckford was already worried about dying because of the conditions in the Connecticut nursing home where she has worked for 23 years. She wasn’t feeling well and says she and her co-workers, facing a shortage of masks, gloves and gowns, had started wearing plastic trash bags over their uniforms for protection as they cared for infected residents.

Beckford, a certified nursing assistant (CNA) in the Alzheimer’s unit at Newington Rapid Recovery Rehab Center in Newington, Connecticut, had been running a low-grade fever but says the facility was only sending workers home if their temperature reached 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit — per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. In an effort to ensure there were enough staff to care for all the residents, Beckford says, employees had been told they were not allowed to take any more time off.

“I went to the administrator, like, ‘I am sick, and you guys are still keeping me in here, I don’t have the proper PPE (personal protective equipment) to work with now, and I just don’t want to die,'” says Beckford, 48. Days later, she tested positive for COVID-19.

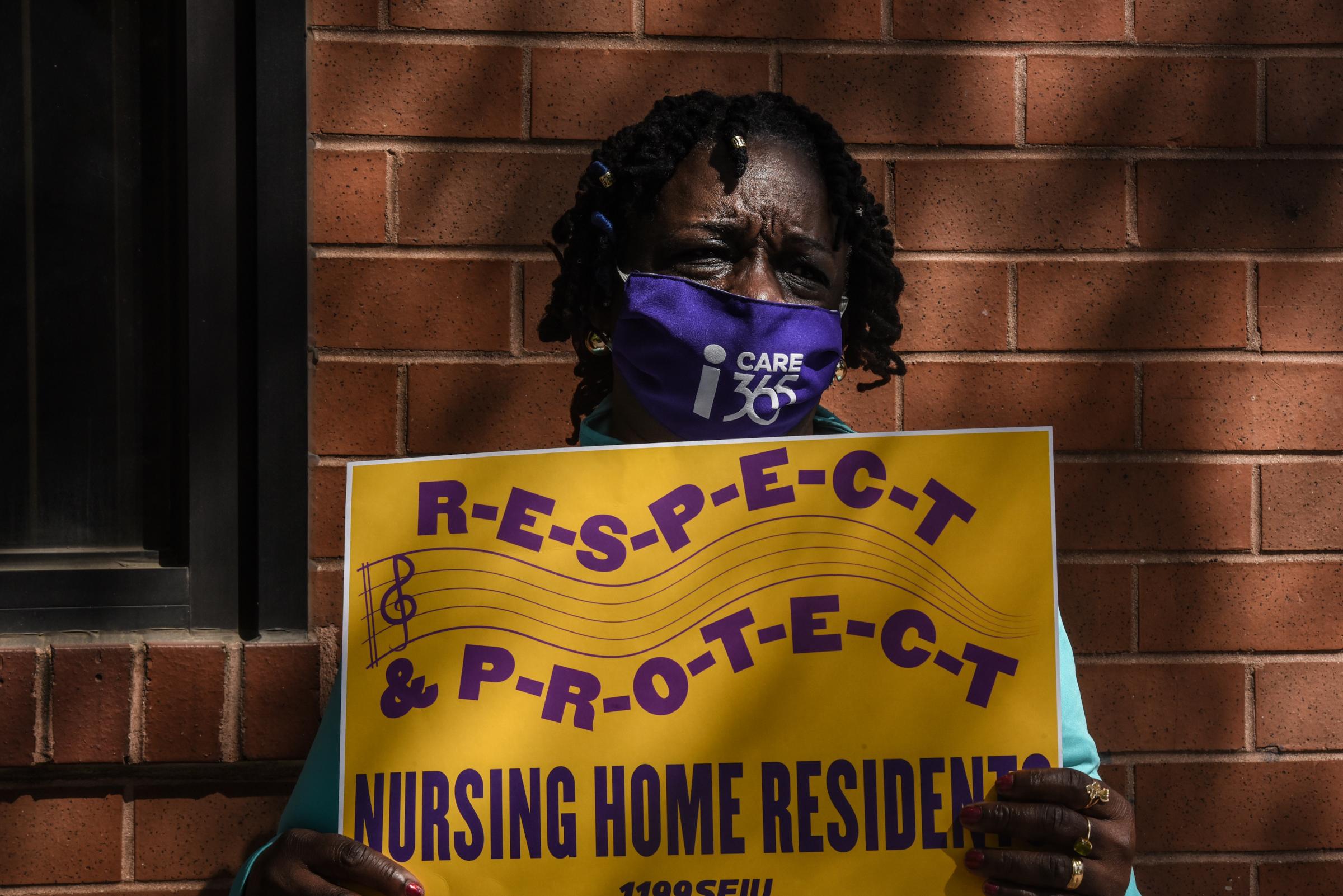

The coronavirus pandemic has devastated nursing homes across the country. There have been more than 35,000 COVID-19 deaths in long-term care facilities, according to the Associated Press — a figure that accounts for about a third of the country’s coronavirus deaths. The industry has been sharply criticized by relatives of the dead, who’ve accused nursing homes of being slow to take action against the virus and of trying to dodge responsibility for their loved ones’ deaths. But nursing home employees, who face serious occupational hazards even in non-pandemic times, say they’re caught in an impossible situation and being blamed for problems rooted in America’s failed elder-care system.

Keep up to date with our daily coronavirus newsletter by clicking here.

They’re struggling to protect themselves and support their families on menial salaries while caring for a population that is among the most vulnerable to COVID-19. Nursing home employees who contract COVID-19 have been forced to use up their limited sick time or vacation time, go without pay, or lose their jobs entirely. Through it all, they have dealt with grief and despair as elderly residents to whom they’ve become emotionally attached become sick with COVID-19 and die.

“The worst thing that I get upset about is hearing the word hero, hero, hero being thrown around for us. And no one is treating us as such. We feel disrespected,” says Beckford, who has been on sick leave since April 10 and is still recovering from pneumonia caused by the virus. “I would love to see them give us the proper PPE that we need, give us some kind of compensation, and for goodness sake, I don’t have any more vacation or sick time now, and the year is just beginning. Give me back some kind of compensation and put back my time.”

Newington Rapid Recovery Rehab Center denies Beckford’s allegations, including that employees were forced to use trash bags for protection. “At no time has our staff been without appropriate PPE. The building has been properly staffed throughout the crisis,” it said in a statement, adding: “We have been strictly following the CDC protocol for health care workers.” When she recovers, Beckford plans to return to work there.

But recent lawsuits — brought by relatives of nursing home workers who died of COVID-19 and by former nursing home employees — are drawing attention to the conditions within some facilities that workers say put them and patients at unreasonably high risk.

Carlenia Milanes, a licensed practical nurse, spent weeks unwittingly caring for COVID-19 patients at Alaris Health at Hamilton Park in Jersey City, N.J., while the facility initially prohibited employees from wearing masks, according to a lawsuit filed April 22. The suit claims the nursing home hid coronavirus cases from employees, “refused to test patients and pressured staff to work even if they had symptoms of the highly contagious and deadly disease, all while patients and staff alike were dying of COVID-19.”

On April 3, Milanes sent an email to Jersey City officials sounding an alarm and saying the nursing home’s strategy “is to put blinders on even at the cost of human life.” “Something needs to be done or more people and staff get sick and possibly die,” Milanes wrote, according to the lawsuit. “I need your help.”

Milanes, 28, called in sick for the following day after developing symptoms of COVID-19, but her suit alleges that she was told she would be fired if she didn’t present a doctor’s note. In her lawsuit, Milanes also alleges the facility allowed seemingly healthy residents to share rooms with residents who had symptoms of COVID-19.

By May 27, there were 110 COVID-19 cases among the facility’s residents, including 31 deaths, and 42 COVID-19 cases among staff, including two deaths, according to data reported to the state. Milanes was among the affected staff members; the COVID-19 test she took on April 6 came positive.

“I’m not afraid to work. I would take care of anyone, but if I’m sick, how am I going to be any good for a patient?” says Milanes, a single mother whose 7- and 10-year-old daughters have since shown symptoms of COVID-19 as well. “I’m somebody’s mother. I’m somebody’s sister. I’m somebody’s daughter. And granted yes, this is what I signed up for, but protect me.”

LaDawn Chapman, a CNA at the same facility, also filed a lawsuit against Alaris on April 22 that echoes many of Milanes’ allegations, including that the facility lacked adequate protective gear for employees and did not notify employees about coronavirus cases. The lawsuit says Chapman was likely exposed to COVID-19 through a patient and multiple coworkers and had a doctor’s note advising her to self-isolate for two weeks. She was told that unless she had symptoms of the disease, she had to come to work, her lawsuit alleges.

Both women say they were fired, but Alaris Health denies this. Five days after the suits were filed, Alaris Health sent each woman a letter saying they were “mistaken” about being fired and setting dates that each was expected to return to work. In a statement, Alaris spokesperson Matt Stanton also denied the lawsuits’ other allegations.

“I can tell you that each and every allegation in this case is false,” he said. “No employees were terminated. At no time was information withheld from staff, our residents or their loves ones [sic]. Thankfully, adequate PPE has never been an issue at any of our facilities. In fact Alaris required N95 masks and PPE for all staff well before the (New Jersey Department of Health) and CDC mandates. Finally, no employees were ever pressured to work while sick. Staff showing COVID-19 symptoms were sent home and required to adhere to strict return to work protocols as published by the NJ DOH.”

In Texas, Maurice Dotson, a CNA at West Oaks Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Austin, died on April 17 after contracting COVID-19. His mother sued the nursing home on May 13, accusing it of failing to provide staff with protective equipment and exposing workers and patients to “unreasonable risks of serious harm.” A spokesperson for West Oaks said Dotson “touched countless lives and was a respected and comforting presence,” but declined to comment on pending litigation.

Leaders in the long-term care industry have argued that nursing homes need more support and funding from state and federal governments. And the industry has sought immunity from potential lawsuits related to the pandemic, but the laws and executive orders granting them immunity from civil liability in some states, including New Jersey, might not protect them from all legal claims.

“While I understand that you can’t judge a nursing home that’s in the midst of a pandemic by the same standards you would on a regular day, it doesn’t give these nursing homes the license or the right to behave recklessly or engage in willful misconduct,” says Bill Matsikoudis, an attorney who is representing nursing home workers and residents in the lawsuits against Alaris Health at Hamilton Park.

‘It’s not getting better, it’s getting worse’

Infection control has long been a challenge in long-term care facilities, where hands-on care is a necessity, and the pandemic has exacerbated that problem. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, in a report released May 20, said that 82% of nursing homes surveyed from 2013 to 2017 were cited for infection prevention and control deficiencies.

Meanwhile, the median pay for nursing assistants was $29,640 last year — just above the national poverty level for a family of four, which is $26,200. By comparison, the median salary for a full-time worker last year was about $49,000, according to weekly earnings data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In part because of that low pay, many nursing home employees work second jobs, which increases their risk of contracting the virus and unwittingly carrying it to residents.

“If the aides were paid a living wage, they would not need to have multiple jobs,” says Joanne Spetz, director of the Health Workforce Research Center for Long-Term Care at the University of California, San Francisco. “That forces the workers to put themselves at more and more risk to support themselves, and that also puts their clients at risk and their residents at risk.”

And while staff shortages have long been an issue at nursing homes, the problem becomes worse when workers stay home sick. As their colleagues take on the extra work, the care and time they’re able to give patients suffers.

The median pay for nursing assistants was $29,640 last year — just above the national poverty level for a family of four, which is $26,200.

“A lot of nursing homes are worried,” says David Grabowski, a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical school who focuses on long-term care. “Who steps in here? Maybe it’s the National Guard, maybe it’s contract nurses. But it’s not like these places have a big roster of folks ready to plug into these positions.” In New York City on May 20, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city would provide staff to fill in for nursing home workers who contract COVID-19 and must stay home.

All of this suggests that the looming shortage of elder care workers in the U.S. is likely to worsen, now that the pandemic has laid bare many of the problems in the industry. “It’s a two-way street. We need to pay them a rate commensurate with all we’re asking of them and support them,” Grabowski says. “Otherwise they’re not going to be there to do this.”

The response to coronavirus outbreaks in nursing homes has varied by state. In Maryland— where nursing home residents and staff account for more than half the state’s coronavirus deaths — Gov. Larry Hogan required in early April that all nursing home workers wear masks at all times and then ordered testing of all residents and workers, whether they showed symptoms or not. In New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo recently mandated twice-weekly COVID-19 testing of nursing home workers. But he also faced criticism from the nursing home industry and residents for originally directing long-term care facilities to accept back coronavirus patients released from the hospital. He walked back that policy on May 10 amid concerns that it would cause the virus to further spread within nursing homes.

On May 5, Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker introduced legislation that would require nursing homes to provide workers with training in how to avoid COVID-19 exposure, sufficient personal protective equipment, increased testing and at least two weeks of paid sick leave. Parts of the bill were incorporated into the new $3 trillion pandemic relief package that passed the House, but that legislation is unlikely to become law as it faces overwhelming Republican opposition in the Senate.

Following complaints about a lack of transparency within nursing homes, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is now requiring them to report coronavirus cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as to residents and their families. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) — which has received at least 230 COVID-19 complaints related to nursing homes — released guidance on May 14 aimed at reducing workers’ exposure to the virus. It recommends that facilities encourage workers to stay home if they’re sick, develop a process for decontamination and reuse of protective gear, and train workers on how to protect themselves.

Debbie Berkowitz, program director for the worker safety and health program at the National Employment Law Project, says there needs to be stronger oversight at state and federal levels and that nursing homes should ramp up training of employees on treating COVID-19 and increase testing of workers and patients within their facilities. She says any solution will also hinge on staffers having enough protective equipment — a consistent obstacle for frontline workers.

“Mentally, physically, emotionally, you’re fighting a disease. And on top of that, we have to fight administrators to give us protective gear,” says Nicole Jefferson, a part-time CNA at Apple Rehab in Rocky Hill, Conn., who thinks of her 3-year-old and 14-year-old daughters each time she enters a COVID-19 room. “I don’t want to die. I don’t want my kids to die. What more can we do?”

An Apple Rehab administrator reached by phone said “we have plenty of protective gear,” but directed further questions to a spokesperson, who did not respond to a request for comment.

In Illinois, thousands of nursing home employees who are members of the SEIU Healthcare union had voted to strike on May 8, before reaching a last-minute deal on a new contract. It includes an increase in base pay to $15 an hour, an extension of $2 hazard pay and five additional paid sick days for coronavirus.

The new contract also guarantees that staffers won’t be required to work without adequate protective equipment. But Francine Rico, a CNA at the Villa at Windsor Park nursing home in Chicago who was on the bargaining committee, says workers still don’t have enough. Rico says she was given a raincoat to wear for protection and takes care of her N95 mask “like it’s gold.”

“How do they expect for this virus, this pandemic, to even lift if we’re still wearing the same PPE gear in and out of the rooms?” says Rico, 52. The nursing home has had 143 cases of coronavirus and 33 deaths as of May 23, according to data reported by the state.

In a statement, Villa at Windsor Park called its workers “heroic” and said the facility is screening staff for symptoms at the start and end of their shifts. “In as much as there has been a national shortage of PPE, Villa at Windsor Park has at all times had sufficient levels PPE, including those necessary for infection control and personal protection, to ensure that we meet the needs within the center,” the statement said.

Rico’s sister, Eartha Sears, is a CNA in the same facility and says she recently returned to work after using up all her sick time and vacation time while recovering from COVID-19. “I wish they’d [use] better judgment about safety — not just our safety, the residents’ safety as well,” says Sears, 56. “Because it’s not getting better, it’s getting worse.”

Meanwhile, employees are contending with the mental and emotional toll of continuing to work in places ravaged by illness, losing residents and coworkers they’ve known for years.

“They teach you when you’re in school as a CNA not to take any of this personally,” says Beckford. “But if you’re a human being with a heart, you’re going to feel something for the people that you’re working with for such a long time.”

Beckford graduated with a master’s degree in 2018, planning to transition into social work, but she stayed at the nursing home to continue caring for her oldest residents. “Unfortunately, once I return to work, the majority of my residents will not be there,” she says.

Milanes says many of the residents she cared for have died in the past two months. She says she recently received a job offer from a different nursing home, and she plans to start when she tests negative for COVID-19. But everything about the career she once loved has changed.

“Maybe I’m afraid because I cared about them, and I know that they’re all dead,” she says. “I’ve cried, I just don’t think that I’ve had time to really grieve.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com