On the warm afternoon of June 8, 1844, an armed patrol of 15 Texas Rangers was traveling through the Hill Country of south central Texas when it came under attack by 75 Comanche warriors. Until this day, encounters between the Rangers and Comanche—fierce and able fighters who’d been raiding Texan settlements for years, as the Spanish and then Anglo presence intruded on their homeland—had generally gone badly for the Rangers. Not only were they often outnumbered, they were also effectively out-weaponized. The Rangers had better guns, but even the best guns at the time needed to be reloaded after every shot. At a minimum, reloading took 30 seconds. Meanwhile, the Comanche, mounted on fleet mustangs, galloped toward them, firing arrows at a rate of 20 or 30 per minute. Before a Ranger reloaded, he was likely to be dead.

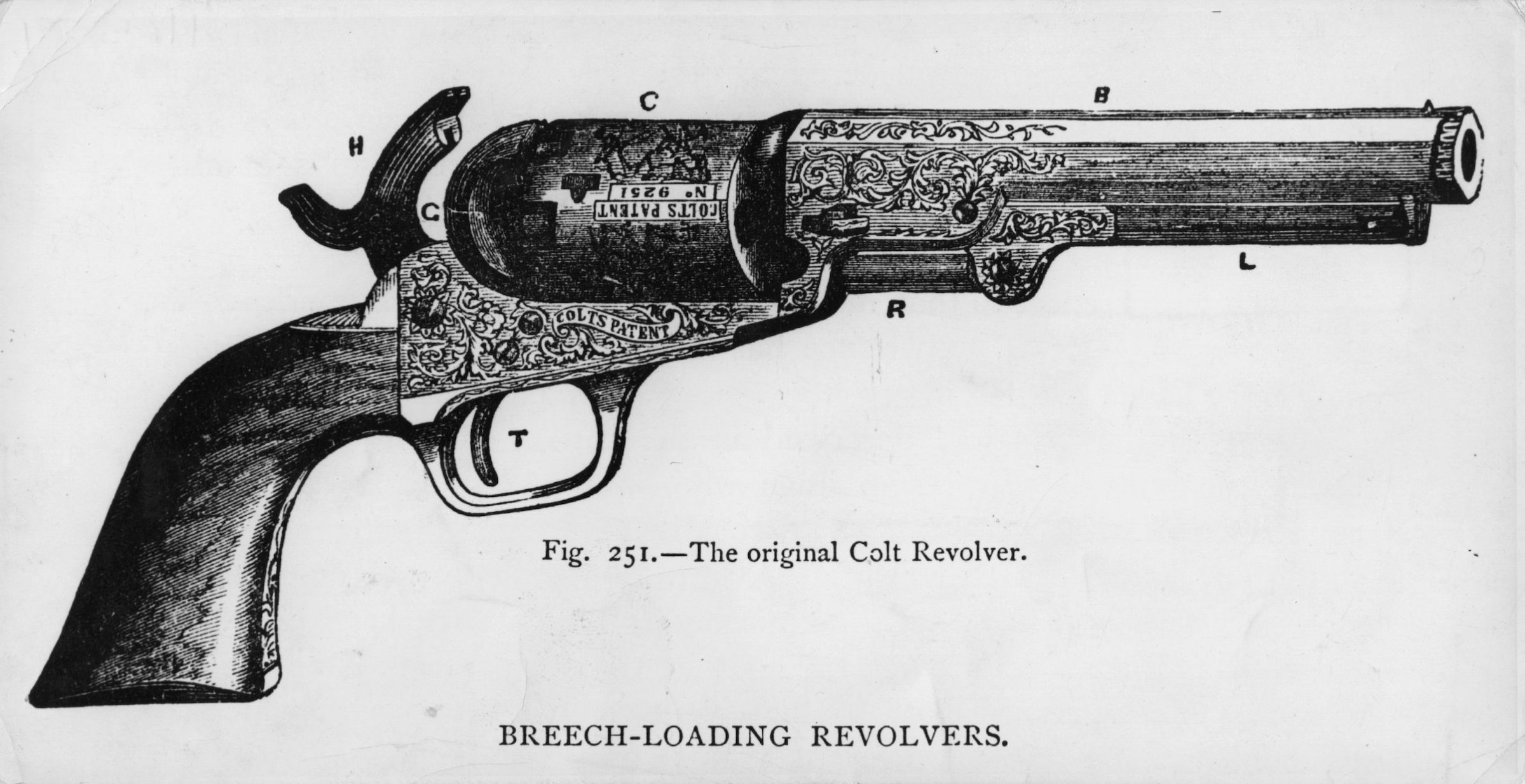

But the Rangers had a surprise in store for the Comanche that day. They’d acquired a cache of a new kind of pistol, called a repeater, or a revolver, patented eight years earlier by a young man from Connecticut named Samuel Colt. The first practical mass-produced, rapid-fire gun in history, Colt’s pistols had a rotating cylinder that could be loaded with five bullets (later six) and turned after each shot to bring the next chamber into alignment with the barrel.

Now, as the Comanche attacked, they galloped into a blaze of gunfire such as they had never experienced, “a shot for every finger on the hand,” as one of the astonished Comanche leaders is said to have later put it. Almost at once, the balance of power in the American west shifted. “We now come to the first radical adaptation made by the American people as they moved westward from the humid region into the Plains country,” wrote Texas historian Walter Prescott Webb in his 1931 history of the American west. “The story of this adaptation is the story of the six-shooter, or revolver.”

How Americans view this story today probably corresponds to how they identify politically. Conservatives, especially those who embrace the right to bear arms as a foundational American liberty, are likely to see the western debut of Colt’s revolver as a demonstration of American ingenuity applied to dangerous circumstances. Liberals are more likely to focus on the violence unleashed by the guns, and by the numerous rapid-fire guns that came later. A deeper look at the history that surrounds the moment suggests that both of these views are warranted, and neither excludes the other.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Colt’s invention led to a great deal of unnecessary bloodshed. It sped the mass slaughter of Native Americans, including women and children, at the hands of U.S. Army cavalry, in numerous shameful massacres. It also set off an arms race that would lead to far more lethal rapid-fire weapons, from the Winchester rifle to Maxim’s machine gun to the AR-15 (which the Colt company ceased manufacturing last year). But the revolver can’t be dismissed as nothing more than an unfortunate development in human progress.

The famous saying about Colt’s guns—“God created man, but Sam Colt made them equal”—captures the very real way the gun changed life for 19th century Americans. It endowed men (and women, too; many became loyal customers) with a confidence to enter hazardous environments in which they might be outnumbered or overpowered. It allowed people to travel solo into wilderness, and it was a godsend to those who dared to go west on the Oregon trail. Americans today can debate whether our westering forebearers, in pursuit of land and gold and better lives, had a right to go where they were not wanted. But there is no arguing with the risks they took in going. Attacks by Native Americans in the west were infrequent but deadly. Fellow white settlers, too, were a serious threat in the gold fields of California and Colorado, where greed was rampant and law enforcement scarce.

Appreciating this may not change our opinion of guns. But it might help us understand that America’s gun culture was not born of insanity or blood lust. Many of Colt’s early customers were simply people doing their best to respond prudently to risk. The larger point here is not to defend or applaud Colt and his gun. Rather, it’s to commend American history as an antidote to the entrenched positions we tend to assume when it comes to thorny issues like guns.

At a time when nearly every matter confronting the American public, from our weather to our immigration policy to our response to a pandemic, is quickly shorn of nuance and reduced to Manichaean politics, history nudges us to view American life less dogmatically. Because their lives occurred in different contexts and were driven by different exigencies than our own, our forebears resist sorting themselves neatly into white hats and black hats. Good and evil existed in the past, but it was not always clear who was which. Consider the abolitionists who dedicated themselves to freeing slaves but were often vehemently anti-Catholic, which meant anti-Irish and anti-immigration. Or the great generals who led the union army to victory during the Civil War—Sherman, Sheridan—then went on to command military campaigns intended to wipe out Native Americans. We can’t enter the past without getting discombobulated in our moral and political certitudes.

Colt himself was a devilishly complicated man whose moral compass usually pointed in the direction of his own self-interest. We have every reason to judge him harshly for his rapaciousness, his duplicity and his contempt for law (when called before the House of Representatives to testify on charges that he’d bribed Congressmen, he showed up drunk), but we also have to admire his energy, his ingenuity and his ridiculous perseverance. Colt was more than happy to sell guns to the South right up until the bombing of Fort Sumter in April of 1861. But immediately after Sumter, he expanded his armory in Hartford, Conn.—already the most advanced factory in the world—nearly doubling its size and making it one of the most important resources of the North.

The past is a morally untidy place. As a result, it is also a place, perhaps the last one left, where we can meet and lower our weapons for a while. History probably won’t solve our disagreements about guns or anything else. But it might allow us, for a moment, to consider, with more open minds and hearts, the complicated land we share.

Jim Rasenberger is the author of Revolver: Sam Colt and the Six-Shooter That Changed America, available now from Scribner.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com