Much of New York City has been idle since the coronavirus lockdown was declared two months ago, but not the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal, an 88-acre shipping and distribution hub built in the 1960s on the east side of the city’s inner harbor, opposite the Statue of Liberty. Day and night, trucks back up to loading bays while 130 workers scamper between three football-field-size warehouses, waving in drivers and inspecting their freight.

The traffic here is no longer in goods arriving from around the world, however. It is in the dead.

The corpses arrive from across the city. Since mid-April, the bodies of New Yorkers have been pulled from homes, hospitals and alleyways, zipped up in black body bags and brought here for processing. Some died hours earlier; others have been gone for days, or even weeks. One by one, they are examined and entered into a computer tracking system. Then they are pushed up a ramp to a loading dock and stacked on wooden racks with 90 other corpses inside one of dozens of 53-ft. refrigerated tractor trailers set at 37°F to 39°F for storage.

The makeshift morgue is just one stop in a citywide cavalcade bearing an unfathomable number of bodies. Since March 14, COVID-19 has killed some 20,000 in New York City; at the height of the pandemic on April 7, two dozen people were dying every hour. But those figures don’t capture the competing challenges that the scale of death has created on the ground.

The first is logistical: How do you handle that many dead bodies in a safe and hygienic manner? The pandemic has overwhelmed the network of funeral parlors, mortuaries and morgues designed to process the dead. At the worst moments, hospitals loaded corpses onto refrigerated trucks with forklifts. Medical examiners set two-week limits to claim bodies before they were sent in pine boxes to paupers’ graves on Hart Island. Funeral homes stacked caskets in spare rooms, hallways and private chapels. Crematories’ brick ovens collapsed because of overuse.

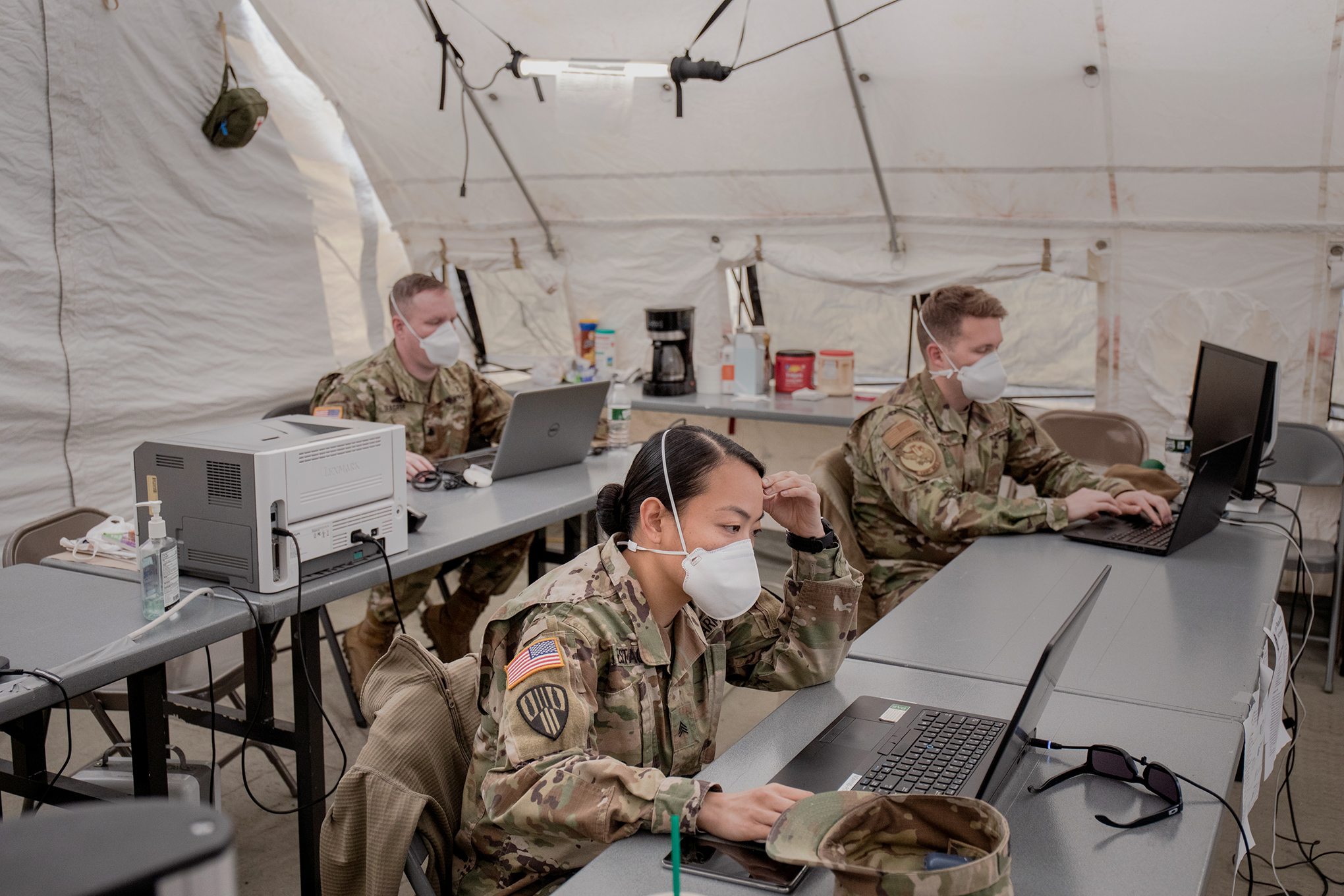

The harder challenge is psychological. How do you maintain your humanity in the face of so much dehumanizing death? Amid the crisis, the usually discreet network of humans entrusted with caring for our dead and helping us mourn has struggled. Reinforcements from the National Guard have been called in, with part-time soldiers like Senior Airman Steve Ollennu pulled off his job installing communications equipment to retrieve bodies as grieving family members say their last goodbyes. City officials like Frank DePaolo, who handled the dead after 9/11 and now oversees mortuary operations for the chief medical examiner’s office, are working 12-hour shifts trying to ensure a modicum of respect for those brought into the disaster morgues. Funeral directors like John D’Arienzo search for small symbolic steps to honor the deceased in rituals so anonymous and restrictive, they are no longer called wakes or visitations but rather “identification ceremonies.”

TIME spent more than a month observing and traveling and speaking with more than three dozen people in New York City’s procession of death, gaining access to every step of the journey from body collection to mortuary inspection to burial. What emerged is a picture of professionals trying to balance the grueling practicalities of processing hundreds of bodies per day with the compassionate imperative to honor the deceased and offer survivors the chance to mourn and some semblance of closure. The virus has kept us from saying goodbye at a hospital bedside or finding peace at a funeral. “We don’t do this work for the dead,” says DePaolo. “We do it for the living.”

The call for help comes in at 3:56 p.m. on May 2. The dispatcher with the medical examiner’s office tells Senior Airman Ollennu, 32, of the 105th Airlift Wing of the New York Air National Guard that a “removal” is needed at a retirement home in Flushing, Queens. Twenty minutes later, Ollennu and his two team members arrive at the rear of the 10-story red brick building and park near the service elevator. Jumping to the pavement, they shed their hats and camouflage jackets and pull on white hooded jumpsuits, blue latex gloves and white plastic coverings over their combat boots.

It is a spectacle for the New Yorkers enjoying the 72°F day. A man walking a white and brown shih tzu stops midstride when he spots the troops looking like spacemen. He promptly moves to the other side of the street, watching as Ollennu and his group disappear into the service elevator with a stretcher. Wordlessly, the collection team heads to the basement morgue, where a staffer points a thermometer at each of their necks to ensure they aren’t running a fever. The body of an elderly woman awaits them. After a medical examiner’s official confirms her identity, the troops zip her into a body bag, then place her in a second bag to ensure no bodily fluids escape.

The team wheels the corpse back the way they came, through the basement, into the elevator, out the service entrance to the back of the medical examiner’s truck, where they gently secure the woman’s body. Standing outside the truck, the troops ball up their protective equipment and toss it into a bucket marked bio-hazard. Then they take turns spraying themselves with disinfectant.

For two months, 30 three-person teams of National Guard members have joined officials from the medical examiner’s office in this ritual. Many of the troops had never so much as touched a dead body before. Now they see more corpses in a week than many soldiers see in a nine-month combat stint. It’s not just the COVID cases. They’ve had to help on all New York City deaths: picking up a suicide jumper off the pavement; holding their breaths to haul out two-week-old corpses from hoarders’ apartments; and tiptoeing around blood spatter at murder scenes. “Once you see it, you can’t unsee it,” Ollennu says. “You can’t unsmell it either.” The National Guard has a chaplain and behavioral-health specialists available if the troops need to talk about the scenes they deal with all day.

Ollennu’s military occupation is actually to install and maintain communications equipment. He’s had to learn body removal on the job. Apartment buildings are a challenge. Hallways are often narrow. Sometimes the elevator is broken, forcing the team to haul a lifeless body down multiple flights of stairs. “It’s hard when you have to handle a body that’s been decomposing for an extended amount of time because the body is weak, it’s brittle in some areas, the skin is ready to peel off,” Ollennu says. “You try to handle it in a respectful manner, so the survivors can see that their loved ones weren’t just manhandled and thrown in a bag.”

Grieving families are often present, which adds another complexity. It’s often the last time relatives are able to see their father, mother, son or daughter. Many have a deep fear that their loved one will get lost among the thousands of corpses held by the medical examiner’s office. The team reassures them that they maintain a number-coded tracking system, so their family member or friend won’t be misplaced.

In one sense, Ollennu is doing this for his neighbors. He grew up in the city. His father, a taxi driver born in Ghana, still lives in Harlem. Sometimes he collects the dead from Lincoln Medical Center, the hospital where he was born.

It was dusk by the time Ollennu’s team dropped off the last body of their shift at the makeshift morgue. As they pulled in, members of the medical examiner’s office checked their victim and took down her name, birth date and other information. Nearby, other workers wheeled unidentified bodies to the refrigerated truck dedicated to those who arrive unclaimed.

The South Brooklyn Marine Terminal became a massive crisis morgue thanks to Frank DePaolo, 60. His COVID-19 response plan drew on his experience coordinating operations following the 2001 terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center. The warehouse complex was previously used to sift through debris to find remains of missing 9/11 victims. Another COVID-19 morgue in Manhattan, in an area formally known as Memorial Park, also held the remains of victims in the attacks.

DePaolo, who worked as a paramedic before climbing the ranks of the medical examiner’s office, even lured back veterans from the 9/11 emergency response who had left. John Scrivani, 48, retired from New York City disaster-response management about a decade ago to enjoy a quieter life in Virginia. DePaolo persuaded him to temporarily leave his job with the Virginia department of transportation to help coordinate the recovery and transfer of remains from hospitals. “When I saw what was going on, sitting at home wasn’t an option,” Scrivani says, standing on a morgue loading dock as soldiers, firefighters and emergency personnel scuttle back and forth.

Over the past two months, the medical examiner’s office has transformed into a hub-and-spoke organization for the collection, transport and storage of corpses. It has installed more than 100 refrigerated trailers outside 58 hospitals in all five boroughs. A planning team plots out response calls in order of urgency. A fueling truck is sent around to fill up each refrigerated trailer once a day. All of it happens 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The core mission is to vastly expand the city’s storage capacity, easing the burden on undertakers and gravediggers who are backlogged with bodies and inundated with requests. Before the pandemic, the medical examiner’s traditional morgues could store up to 900 bodies. Capacity is now at least five times that.

On a recent Saturday, standing in front of more than two dozen refrigerated trailers holding hundreds of dead New Yorkers, DePaolo tried to find words to express what he is experiencing. The afternoon sun reflected off the trailers’ white panels. A breeze carried the whir of generators and the scent of gasoline. “People have no idea this is going on,” DePaolo says above the din. “It’s like another world.”

The logistical challenges are complicated by emotional ones. DePaolo is leading an effort that has no contemporary precedent; the number of dead far surpasses the casualties seen on modern battlefields. And the 12-hour shifts are taking a toll as all 800 medical-examiner employees, 350 U.S. troops and 75 federal personnel assigned to the office work at their limits to handle all the bodies. “People will work seven days a week if you don’t tell them to stay home,” DePaolo says. “We know from past experience that’s not healthy.”

The D’Arienzo Funeral Home in Brooklyn has never had long-term refrigeration capacity for the bodies it takes in, and for 86 years that wasn’t a problem. “I do about 100 funerals a year, which mathematically works out to about seven a month,” says John D’Arienzo, 58, the third-generation director. “I did 60 funerals in April.”

He’s done what he can to free up space inside. The furniture in a small, dimly lit chapel was removed to hold caskets, stacks of long cardboard boxes known as cremation containers, and cartons of much needed plastic protective equipment provided by the city. He had to use a spare room in back, behind the coffee-colored curtains in the visitation room, as an emergency space for up to six bodies. He sets fans and a cooling system to maintain 50°F, which isn’t cold enough to keep the bodies from decomposing after a day or so.

D’Arienzo has worked to maintain a lifelong pledge, passed on from his father and grandfather, to help every mourning family that enters his front door. But that was before COVID-19. Now, most days, he keeps the door locked and his phone off the hook. “Worst thing I’ve ever done in my life, as a person and a funeral director, was to tell a family I couldn’t help them,” he says. “And there were days I was telling 30 to 35 families, ‘I can’t help you.’”

As president of the Metropolitan Funeral Directors Association, D’Arienzo hears from undertakers across the city. “Everyone is overwhelmed,” he says. “Everyone is at full capacity. Everyone is trying to service anybody and everyone that they can.”

Even the people he can help are not able to mourn their loss normally. Limits on public gatherings compound the pain of grief-stricken families, who must cover their mouths and noses with masks and refrain from touching one another or the deceased’s body. The polished dark wooden chairs in D’Arienzo’s carpeted visitation room have been separated 6 ft. apart and pushed to the oak-paneled walls.

Rather than a traditional hours-long visitation service with flowers and clergy, funeral directors are holding “identification services” so a handful of immediate family members can say a prayer or two. It is a ceremony without catharsis. Some New York City funeral homes have arranged livestreams on platforms like Skype or Facebook.

The struggle to keep up has turned ugly at some facilities. On April 29, at the Andrew T. Cleckley Funeral Home in the Flatlands section of Brooklyn, police found four rented trucks parked on a busy street with about 50 decomposing bodies inside. The discovery was made after a neighbor reported a foul odor and dripping fluids coming from the un-refrigerated vehicles. “I have no idea in the world how any funeral home could let this happen,” Mayor Bill de Blasio told reporters.

But it’s not that easy with every person trained to handle the dead in New York City overwhelmed. Green-Wood Cemetery sprawls out over 478 acres of rolling hills in west Brooklyn. Burials have jumped threefold, to as many as 69 per week. “In my 48 years here, I’ve never seen anything like it,” says cemetery president Richard Moylan, 65, who started cutting grass on the grounds as a summer job in 1972.

Moylan’s gravediggers wear face masks and hazmat suits for confirmed coronavirus victims. “The family has to stay away from us,” says Janusz Karkos, 43, who was raking soil over the newly covered grave of a COVID-19 victim. “Things are very different for burials. So few people, so little ceremony.” He motioned toward a single bouquet of red and white roses that says Uncle and Brother. “Usually, the number of flowers on a grave like this would come up to our knees,” he says. “But there’s no wake, no funeral, so no flowers.”

Faced with limits on funeral attendance and social-distancing restrictions at grave sites, many families are opting instead for cremation. At Green-Wood, the number has tripled to more than 150 each week. New York State regulators realized in early April that demand for cremations would rise, so they loosened restrictions to allow crematories to operate around the clock. All five of Green-Wood’s cremation ovens now burn up to 1,800°F for 16 hours a day. (The remaining eight hours are needed for recovery time.) The overuse has caused two of the ovens to break.

All four city crematories have backlogs stretching to a month. None has ever had a wait list before. Funeral directors have resorted to driving bodies to crematories in Vermont, Pennsylvania, Connecticut—anywhere that’s not overwhelmed.

What does the work of Ollennu, DePaolo, D’Arienzo and Moylan amount to in the end? In the most basic sense, it is about preserving public health. At a time when strangers are told not to come within arm’s distance of one another, these men are taking a risk by handling the dead. But in a moral sense, they have accomplished something more.

Fabian Reyes, 49, called his daughter Fabiola’s cell phone in the early afternoon of March 31, but she couldn’t understand him. “He couldn’t breathe,” says Fabiola, 28. “I just told him don’t give up.” Then her phone pinged with a text message.

“I won’t make it from this one please take care this virus is serious and is gonna wipe out a half the population, take care of your younger siblings please,” the message read. It was sent at 2:43 p.m. on March 31. Fabian died two weeks later.

It took 24 more days for Fabiola Reyes to obtain her father’s ashes. A Catholic from a large and devout Ecuadorian family, she wanted to hold a traditional wake, funeral and burial for her dad. But once it was clear that they wouldn’t be able to gather together, much less have a formal ceremony, the family settled on cremation. Finally, on May 7, they received Fabian’s ashes and convened a handful of family members outside St. Sylvester Church in Brooklyn for a short blessing ceremony.

The ritual, with attendees masked and 6 ft. apart, was a far cry from what the family wanted. But it was something: a moment to honor and remember Fabian Reyes, whose remains had been borne to the service by people on the front lines. In one of the darkest periods in our history, they have carried their fellow Americans with quiet dignity. As Ollennu put it after a long shift, “We try to treat everyone like they were our own family member.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to W.J. Hennigan at william.hennigan@time.com